Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Picky Eater

For one caterpillar, the benefits of a restricted diet include evading plant chemical defenses

by Amanda Yarnell

June 28, 2004

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 82, Issue 27

A team of Pennsylvania State University researchers has shown that the moth caterpillar Heliothis subflexa restricts its diet to an unusual kind of fruit to avoid food competition, insect predation, and plant chemical defenses.

Unlike other, less choosy caterpillars, H. subflexa caterpillars dine exclusively on the fruit of Physalis plants, which include ground cherries, tomatillos, and Chinese lanterns. The fruits of these plants are encased in an inflated bag known as a calyx. The caterpillars access their favorite food by boring a tiny hole in the casing. Inside, they feast to their heart’s content, then exit via the hole to find their next meal.

By choosing a dietary staple that’s encased in a protective calyx, H. subflexa caterpillars are protected from predators while they eat. Restricting themselves to fruits of Physalis plants brings H. subflexa caterpillars other distinct advantages, too.

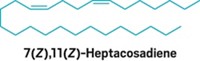

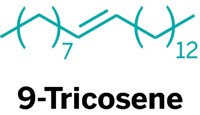

For one, other caterpillars can’t survive on a diet of Physalis fruits alone because these fruits lack linolenic acid, according to new research by entomologist Consuelo M. De Moraes and biologist Mark C. Mescher of Penn State [Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 101, 8993 (2004)]. Linolenic acid, a fatty acid commonly found in plants, is required for the development and metamorphosis of most insect larvae.

But developing H. subflexa larvae don’t require linolenic acid in their diets, De Moraes and Mescher find. The caterpillars therefore face little competition for their favorite food, the researchers point out. These caterpillars’ ability to survive without linolenic acid also prevents their larvae from being infested by parasites that require linolenic acid, the scientists say.

What’s more, lack of this fatty acid guards H. subflexa from plant-recruited predators. Normally, enzymes found in caterpillar spit convert the linolenic acid found in chewed-up plant material into volicitin. When plants detect the presence of caterpillar-produced volicitin, they produce a chemical cocktail that lures wasps to kill the caterpillars.

Thanks to a diet free of linolenic acid, H. subflexa caterpillars don’t produce volicitin, De Moraes and Mescher find. Their ability to circumvent volicitin-elicited plant defenses protects them from being eaten by wasps.

“Physiologically, we don’t know how the caterpillars manage to survive without linolenic acid in their diet,” Mescher says. He and DeMoraes are now trying to figure out their secret.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter