Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Physical Chemistry

On Track for Titan

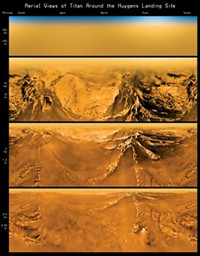

Cassini spacecraft successfully deploys Titan-sniffing Huygens probe

by Elizabeth K. Wilson

January 3, 2005

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 83, Issue 1

On the day before christmas, the Cassini spacecraft successfully released an instrument-laden probe bound for Saturn's giant, smoggy moon Titan. The Huygens probe will reach Titan's upper atmosphere on Jan. 14 and begin a much-anticipated two-and-a-half-hour plunge to the moon's surface that's expected to yield a bounty of chemical information.

To send the probe on the correct trajectory, Cassini was briefly put on a collision course with Titan. Team members breathed a sigh of relief on Dec. 27 after they pulled the craft back into orbit around Saturn.

"We're very, very happy and excited," says Claudio Sollazzo, Huygens operations manager at the European Space Agency (ESA), which manages the probe. "We've come through a major ordeal."

For years, scientists have awaited this encounter with Titan. The only moon in the solar system with a significant atmosphere, Titan is cloaked in nitrogen and splotched with methane clouds. Hydrocarbon lakes may dot the moon's surface. Atmospheric and surface conditions on Titan are believed to be similar to those encountered by early life on Earth. Whether Titan's environment could produce molecules that are precursors to life has been a long-standing question.

Huygens piggybacked on NASA's Cassini during the craft's seven-year flight to Saturn. Explosive devices severed the bolts that attached the probe, which then sped off on its 4 million-km journey to Titan. Engineers followed Huygens' progress by monitoring electrical signals as well as images captured by Cassini.

"We are now absolutely certain the probe is indeed going at the right direction and speed," Sollazzo says.

After a quick Jan. 1 flyby of Saturn's third-largest moon, Iapetus, Cassini will go dormant, readying itself to receive data transmitted from Huygens during the probe's descent. Afterward, Cassini will turn back to Earth and send the information to scientists at ESA's operations center in Darmstadt, Germany.

Huygens carries a gas chromatograph and mass spectrometer designed to identify low- to mid-mass organic molecules, as well as a pyrolyzer that will break apart and analyze aerosols in the atmosphere. The probe isn't expected to survive long after its descent, though the instruments onboard Cassini will continue to monitor Titan.

The Huygens probe launch comes amid new reports about Saturn and its moons from both Cassini and ground-based telescopes.

A recent international study using Cassini's composite infrared spectrometer finds that the carbon-to-hydrogen ratio in Saturn's atmosphere is twice that found on Jupiter. Led by F. Michael Flasar, an astrophysicist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., the study bolsters the reigning "core accretion" model of giant-planet formation, in which a rocky planet seed accretes a large gaseous envelope [Science, published online Dec. 23, http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1105806].

And from the ground-based Keck telescopes on Mauna Kea in Hawaii come the first observations of temperate-region clouds on Titan [Astrophys. J., 618, L49 (2005)]. Unlike Titan's polar clouds, which are thought to be produced by solar surface heating, these midlatitude clouds might result from geological disturbances, say authors Henry G. Roe, astronomy postdoc at California Institute of Technology, and colleagues.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter