Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

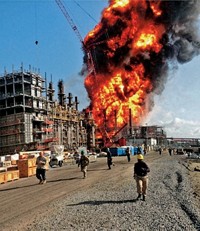

Safety

Plant Security Goes Regional

New Jersey, Contra Costa County roll counter-terrorism plans into plant oversight programs

by JEFF JOHNSON, C&EN WASHINGTON

April 11, 2005

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 83, Issue 15

Contra Costa County, an industrial area northeast of San Francisco, and New Jersey are developing programs that require chemical plants, refineries, and other industrial facilities to adopt plant security measures to reduce the odds and impact of a terrorist attack. Unlike the U.S. government's approach, the county and state are including the plant security oversight in their ongoing plant safety and environmental inspection programs.

They began their efforts in the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. In Contra Costa, county officials have interpreted a California accidental release prevention regulation as giving them authority to require vulnerability assessments.

New Jersey passed a specific law, the Domestic Security Preparedness Act, within one month of Sept. 11. The law requires that state agencies implement a counterterrorism program for some 20 infrastructure sectors in the state, including chemical plants, refineries, and pharmaceutical and biotechnology facilities. For these facilities, the state Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) was given oversight authority.

Nationally, Congress and the White House picked a different path. Because of industry objections, the new Department of Homeland Security (DHS), rather than the Environmental Protection Agency, has authority to oversee plant security efforts. Although EPA lobbied for the authority because of its familiarity with plant operations, the American Chemistry Council (ACC) and a broad range of other industry groups strongly and successfully argued that EPA lacks security expertise.

While DHS is beginning to implement a program to inventory and protect the nation's critical infrastructure, including chemical plants, ACC and other trade associations have put together internal and confidential plant security programs for member companies. But there is no national law requiring plant security plans for all chemical companies, including the majority of chemical handlers that do not belong to trade associations. Last year, plant security legislation died in Congress, killed in the Senate over disagreements on oversight of the security plans and over whether a security law should include provisions to encourage risk reduction, use of less toxic materials, or adoption of inherently safer processes (C&EN, Jan. 31, page 23).

New Jersey and Contra Costa County already have programs promoting inherently safer processes and reductions in the use of toxic chemicals. Neither of their security oversight efforts is related to these regulations, however.

IN CONTRA COSTA, county officials oversee terrorism vulnerability audits and assess plant security efforts at about 40 chemical-handling facilities, says Don Nixon, an accident prevention engineer for the county's hazardous materials program.

County officials, he says, reviewed several existing methods of conducting security vulnerability reviews and developed an approved list of possible methods for the 40 plants to choose from. The county requires the companies to conduct vulnerability assessments and to have a process to ensure that companies take security actions. The county doesn't issue fines for noncompliance but works with facilities to address deficits. But, Nixon says, "that doesn't mean we can't bring in the district attorney if we need to."

Most plants have completed vulnerability assessments or have them under way, Nixon says. Some companies, he adds, had already taken security measures because of requirements from their trade associations.

The program is not backed by specific security regulations, he notes, but adds, "After 9/11, it's pretty hard for a facility to say they won't conduct a security vulnerability assessment."

In New Jersey's case, a law requires security plans. It covers more than chemical plants. Indeed, 20 sectors--from restaurants and schools and entertainment venues to nuclear power plants and chemically related facilities--are included. The law established a Domestic Security Preparedness Task Force, made up of most of the governor's cabinet and three members of the public.

For the chemical, petroleum, pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and other industrial sectors, the law gave DEP responsibility to oversee the program, says Gary Sondermeyer, DEP chief of staff.

For the chemical sector, Sondermeyer says, DEP turned to the Chemistry Council of New Jersey (CCNJ), an 84-member trade association, to draw up "best practices" for plant security needs to counter and respond to a terrorist attack. He emphasizes that the trade association was asked to develop a plan that could be used for small companies as well as the larger ones in its membership.

DEP divided the state's chemical facilities into four tiers and determined that about 400 facilities were the highest priority because of the toxicity and quantity of chemicals they handle and their proximity to large populations. The state did not need to inventory all the plants, he notes, since it already regulates these through several state environmental laws.

The state provided no new funding for the program, Sondermeyer says; hence the need to include security oversight with regulatory inspections, an approach he strongly supports.

"It may be a bit of an overstatement but not much: Our field personnel know these sites as well as the site manager. They go to the sites all the time. They are more process engineers than inspectors. They know every pipe, process flow, and gauge at the plant."

Over the past six months, DEP inspectors have visited the 400 facilities, Sondermeyer says, and have conducted audits of the plants' counterterrorism efforts as they do routine environmental inspections. The security audits, he adds, are more of a detailed checklist than a comprehensive examination.

" 'Did you do a vulnerability assessment? Did you identify remedial measures? Did you do them?' They are that kind of thing," he says. "This is unusual for us. Normally in our programs, we have very precise regulations saying what companies must do to be in compliance, and our field people go in and check that and write up tickets if necessary. But for security, there are no regulations. This program is predicated on sectors developing and adhering to best practices and our oversight to ensure the facility is taking them seriously."

Two years ago, the state attempted to implement a stronger pilot program in which companies would sign an agreement to provide security information in written form to the state. The effort got nowhere.

Chemical companies are quite happy with the program, says Elvin Montero, communications director for CCNJ.

"It was a precedent-setting effort between the state and chemical companies," Montero says. "A lot of the best practices were taken straight out of the Responsible Care security code," he says. "ACC members," he adds, "in most cases have already gone beyond what is required by the state. But for nonmembers, the best practices will put them on the same playing level."

He notes that details for New Jersey's best practices, like ACC's security code, are confidential. "We don't want this information to fall into the wrong hands," he says.

Workers, however, have been totally left out of the development process, says Rick Engler, executive director of the New Jersey Work Environment Council, an alliance of 70 labor, environmental, and community groups. In fact, workers have no idea what "best practices" even are, he says, adding that this greatly weakens the program.

In a letter to the New Jersey governor signed by 67 unions and community and environmental groups, Engler chides the state for basing a security program on industry's "own inadequate security codes" and opposes the memorandum of agreement as putting "a state seal of approval on corporate self-regulation."

His groups urge worker and community involvement in setting security standards that include consideration of inherently safer process designs to limit the impact and possibility of an attack or an accident. They urge third-party verification of security efforts and some form of "controlled" viewing of efforts that companies have taken.

"I am sure some companies are probably doing a good job, but the state and DEP's security efforts have been disgraceful. There has been a total lack of transparency," Engler says.

Over the next year, Sondermeyer says, the state will focus on worker training for security. Calling workers the "eyes and ears" of the program, he says, "best practices are not meaningful if they are not getting down to ranks of people who work at the plants." But, he adds, "it is not clear if best practices will ever be made available to the workers in plants despite the fact that they are relentlessly pushing for them. On the other side of the coin, facilities have significant concerns about their release. It has been hard to find a middle ground."

NEW JERSEY'S DEP security program has had little interaction with the federal DHS, Sondermeyer says. "I have never met a person from DHS," he adds.

Sondermeyer stressed the benefits that could be gained through coordinated regional security efforts or through better interaction with DHS during a recent presentation to a committee of the National Academy of Sciences, which is looking into chemical plant security.

There appears at this time, however, to be little clear interaction between states or between DHS and states. Neither Sondermeyer nor Nixon was aware of chemical plant security programs in other states, and DHS officials could provide no examples of other state efforts.

DHS has identified 300 high-priority, chemically related industry sites nationwide, where more than 50,000 people could be endangered in a terrorist attack. It has conducted site visits at some 160 of the plants, DHS spokeswoman Michelle Petrovich says. The department intends to visit all 300 by year's end, according to a DHS fact sheet.

New Jersey and DHS will likely form a closer working relationship during "TOPOFF 3" terrorism response exercises, set to begin in early April as this article went to press. This full-scale test exercise, however, will focus on preparedness and response to a biological attack in the state, not an attack on a chemical plant.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter