Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Climate Change

Support Voiced For Geo-Engineering Research To Combat Global Warming

by Ivan Amato

September 18, 2006

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 84, Issue 38

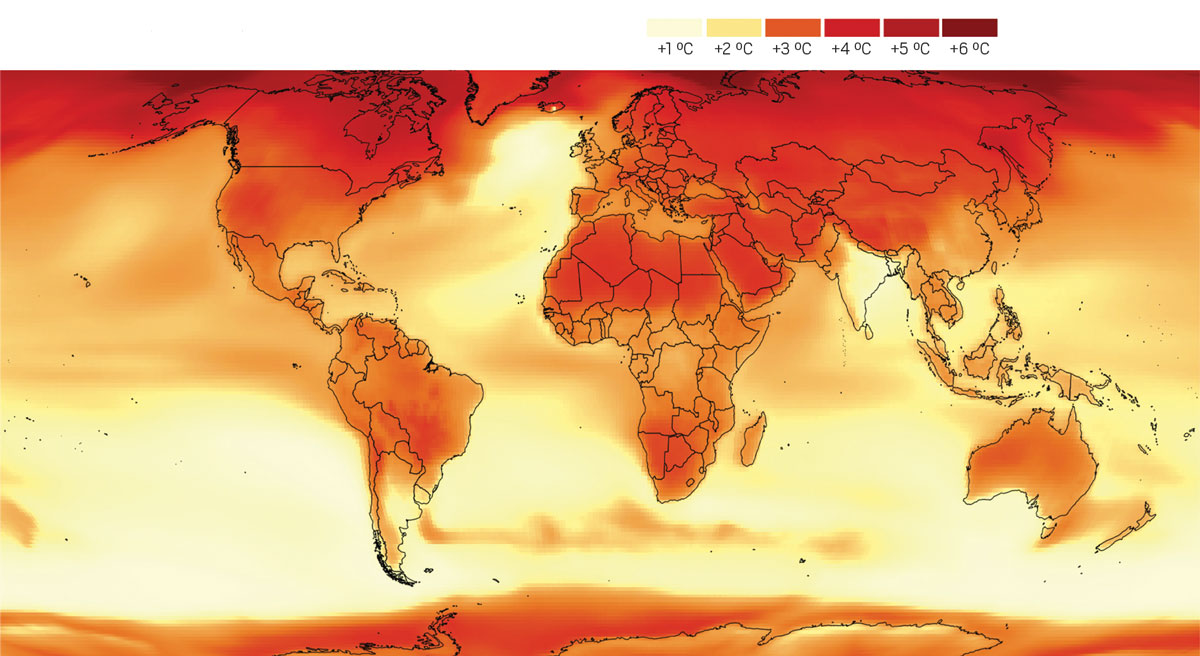

The call to at least consider audacious geo-engineering steps that would fill the stratosphere with globe-cooling aerosols to check global warming got louder last week. In Science, Tom M. L. Wigley of the National Center for Atmospheric Research, in Boulder, Colo., writes that reducing carbon dioxide emissions is the long-term solution to global warming but that nearer term engineering of the atmosphere might provide "additional time to address the economic and technological challenges faced by a mitigation-only approach" (DOI: 10.1126/science.1131728).

Last month, Nobelist Paul J. Crutzen of the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, in Mainz, Germany, made headlines with an essay in the journal Climatic Change calling for more research into the pros and cons of injecting sulfate-based aerosols into the stratosphere as a sunlight-reflecting, cooling foil to global warming (C&EN, Aug. 7, page 19).

Wigley has quite visibly joined Crutzen in this view, this time running several aerosol-producing scenarios through a simple atmospheric model. Adding just 5 million metric tons of sulfur dioxide annually to the stratosphere to produce sunlight-reflecting clouds or a light-scattering haze "would have a significant influence," Wigley says. The 1991 Mount Pinatubo eruption belched twice that amount of sulfur into the stratosphere and had a temporary cooling effect for a few years.

Rutgers University climate scientist Alan Robock worries that the Wigley analysis gives short shrift to uncertainties and ignores such factors as the warming spike that occurred in northern latitudes in the winter following the Pinatubo eruption. Constant aerosol production also could mean "we wouldn't have blue skies anymore," and it could reduce incoming solar radiation enough to hobble such imperatives as replacing fossil fuel with solar energy technologies, Robock says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter