Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Analytical Chemistry

Cleaning Water With 'Nanorust'

Magnetite nanoparticles effectively remove arsenic from water

by Bethany Halford

November 13, 2006

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 84, Issue 46

Rust, olive oil, and a handheld magnet could someday be all that's needed to remove arsenic from drinking water, according to researchers at Rice University. The low-tech solution to a serious problem for developing countries stems from basic research on the magnetic behavior of magnetite (Fe3O4) nanoparticles (Science 2006, 314, 964).

On the basis of extrapolations from the bulk material, an impractically large magnetic field would be needed to draw Fe3O4 nanoparticles out of solution. But how materials behave in bulk isn't always a good predictor of how they'll act at the nanometer scale.

Having just figured out how to make Fe3O4 nanoparticles in various sizes and keep them from clumping by coating them with oleic acid, chemistry professor Vicki L. Colvin and colleagues decided to see how strong a magnet would be needed to pull their new nanoparticles out of solution. "We were surprised to find that we didn't need large electromagnets to move our nanoparticles, and in some cases, handheld magnets could do the trick," she says.

"In this instance, it turns out that the nanoparticles actually exert forces on each other," explains Douglas Natelson, a Rice physics professor who participated in the study. "So, once the handheld magnets start gently pulling on a few nanoparticles and getting things going, the nanoparticles effectively work together to pull themselves out of the water."

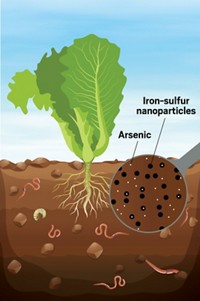

Iron oxides are known to bind arsenic, so Colvin's team decided to see if size, and therefore surface area, made a difference in arsenic remediation. They found that Fe3O4 particles 12 nm in diameter removed nearly all the arsenic from solution, but the same mass of 300-nm Fe3O4 particles eliminated less than 30% of the poison.

"This is interesting work," comments Troy J. Tranter, who is working on arsenic remediation at the Department of Energy's Idaho National Laboratory. "From a practical perspective, it would be interesting to see how this material would be used in an engineered system."

Colvin is trying to tackle that issue. "Although the nanoparticles used in the publication are expensive, we are working on new approaches to their production that use rust and olive oil and require no more facilities than a kitchen with a gas cooktop," she says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter