Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

Liquid-Crystal Lenses

Spectacles made with switchable material could advance vision correction

by Bethany Halford

April 5, 2006

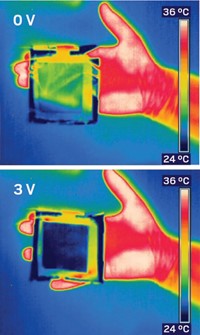

Bifocal lenses and the dizziness and discomfort that come from gazing through them could become a thing of the past, thanks to new liquid-crystal lenses that quickly switch between corrective states (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, published online April 5, dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0600850103).

Because lenses made with nematic liquid crystals can easily change their focusing power, optics researchers have eagerly eyed them as potential replacements for multifocal lenses. But these efforts have been hamstrung by slow response times associated with the relatively thick layers of liquid crystal required.

Now, a group led by University of Arizona optical scientists Guoqiang Li and Nasser Peyghambarian have come up with a lens design that uses a liquid-crystal layer just 5 mm thick. Prototype spectacles made with these lenses can change focus in less than a second and require only low voltage.

The lens design features a liquid-crystal layer sandwiched between two thin sheets of glass. Tiny electrodes photolithographically patterned onto the glass in concentric circles adjust the material's optical properties.

Currently, "the device just has on and off states," Li says. "When it's on, it has focusing power and can be used like reading glasses, and when it's off, it's just like clear glass."

Li and Peyghambarian would like to combine the lenses with an autofocusing device. "In the future, we're going to incorporate near vision, intermediate vision, and far vision," Li adds, so that in theory, you could buy one pair of glasses that could be adjusted throughout your lifetime as your vision changes.

Colin W. Fowler, an optometry expert at Aston University in Birmingham, England, comments, "This device looks very promising as a new technology for the correction of farsightedness," although "it is still some way off from being a practical spectacle lens." He notes that the device has some limitations. "One of the concerns raised about early nematic liquid-crystal devices was their stability in relation to temperature changes," he says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter