Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

Wrinkled Skins

Ion beams create surface patterns for building biosensors and other devices

by Celia Henry Arnaud

January 22, 2007

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 85, Issue 4

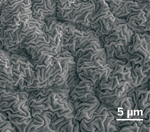

In the right circumstances, wrinkles can be a good thing. On polymer surfaces, wrinkles could provide a foundation for biosensors, diffraction gratings, or microfluidic devices. Using focused beams of gallium ions, researchers at Harvard University and Seoul National University, in South Korea, have now created wrinkles on the surface of the polymer polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0610654104).

When Harvard engineering professor John W. Hutchinson and his colleagues bombard a slab of PDMS with the ion beam, the exposed surface forms a tough skin that tries to expand but is constrained by the underlying polymer substrate. The strain mismatch between the two layers causes the skin to buckle into wrinkles. The new method is less complex and more easily controlled than other methods used to create wrinkled polymers.

The patterns of those wrinkles can be simple and straight or complex and wavy. The researchers can even make hierarchical wrinkles on the polymer with one pattern nested within another. The team was surprised by the more complex patterns and doesn't yet understand the underlying mechanism by which the hierarchical ones form, Hutchinson says.

He suspects that other types of ion beams could also generate wrinkles but not as well as gallium does. The team has already tried argon beams. At the same number of ions per area, argon appears less effective than gallium in inducing wrinkling.

The focused ion beam method "opens the door to cleanly drawing exotic architectures on the surface of PDMS, which in turn will undergo wrinkling to add the desired surface texture," says Christopher M. Stafford, a chemist in the Polymers Division at the National Institute of Standards & Technology. "This will prove extremely useful in the area of microfluidics, where channel designs and architectures are customized—many times on the fly—for a given application."

Hutchinson and his coworkers are collaborating with researchers at Harvard Medical School to study the behavior of living cells on the substrates. They are also using the substrates to make microfluidic devices for mixing and stretching proteins and DNA.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter