Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Analytical Chemistry

Chemophilately

Chemistry stamps depict key discoveries, famous chemists, and chemical errors

by Sophie L. Rovner

December 17, 2007

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 85, Issue 51

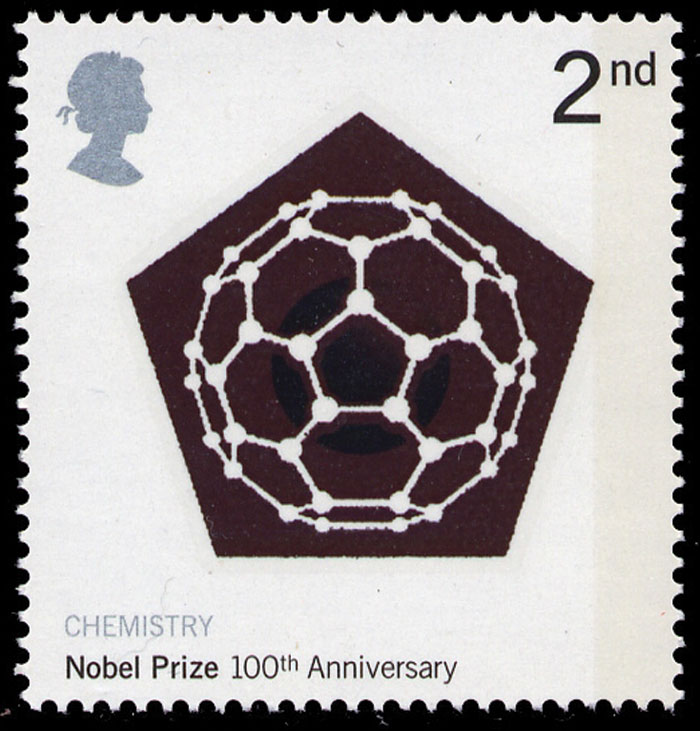

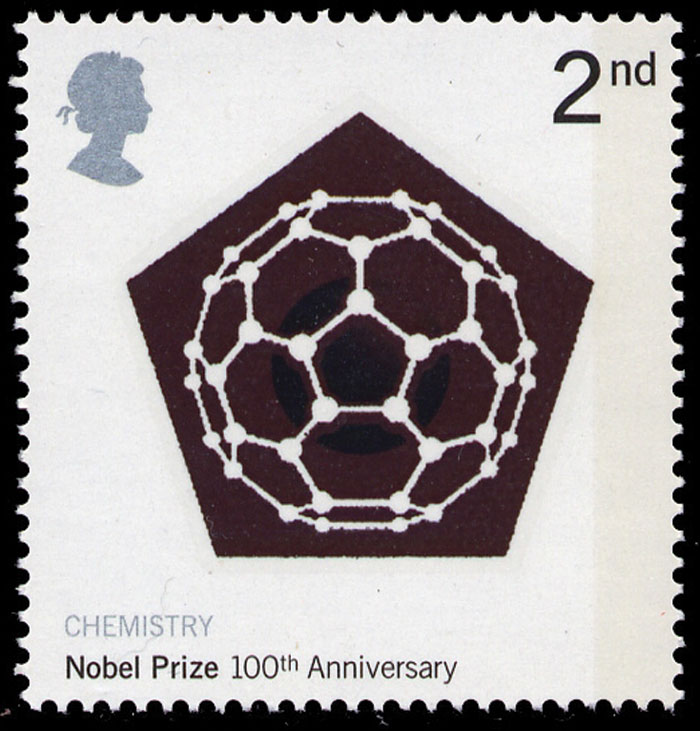

When warmed by a finger, the stamp reveals an ion trapped within the C60 molecule. U.K., 2001

When warmed by a finger, the stamp reveals an ion trapped within the C60 molecule. U.K., 2001

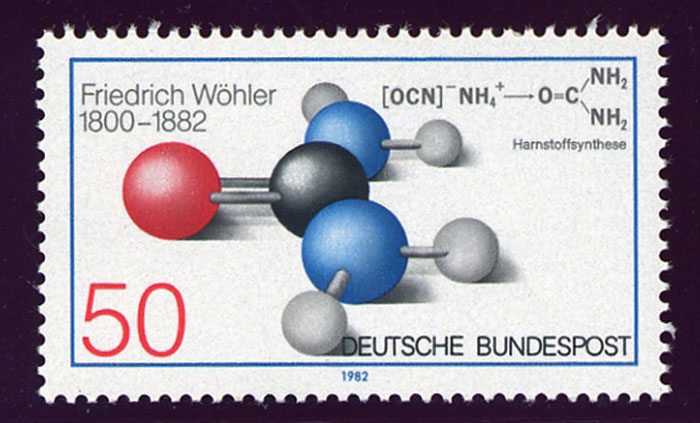

Postage stamps have always been an offbeat means of tracking important historical and cultural trends and events. For a discipline sometimes prone to the Rodney Dangerfield syndrome of feeling that it "don't get no respect," chemistry's fine moments and personages have been well-represented on the world's postage stamps.

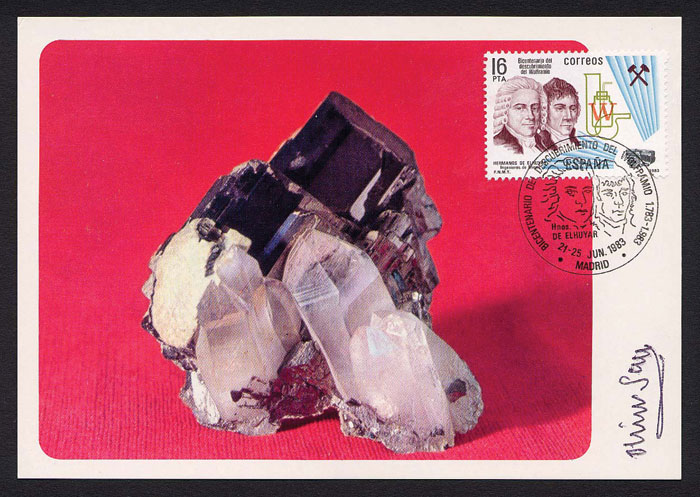

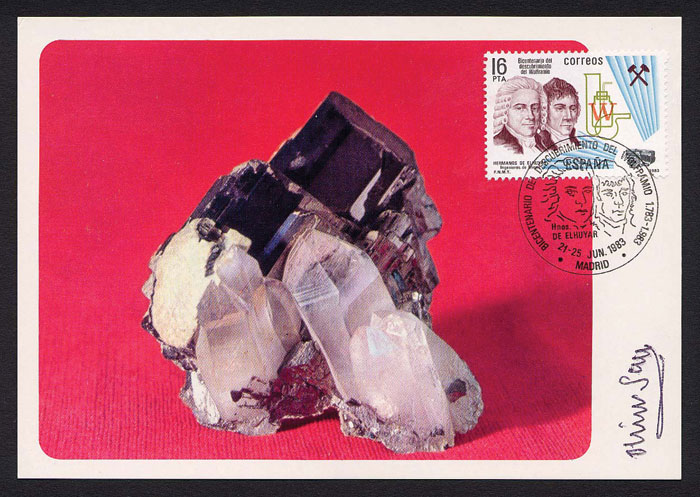

Author and neurologist Oliver Sacks—who published a memoir called "Uncle Tungsten"—autographed this "maximum card," which celebrates the 200th anniversary of the discovery of tungsten. Spain, 1983

Author and neurologist Oliver Sacks—who published a memoir called "Uncle Tungsten"—autographed this "maximum card," which celebrates the 200th anniversary of the discovery of tungsten. Spain, 1983

A stamp honoring Russian chemist Nikolai N. Zinin shows a warped version of aniline. U.S.S.R., 1962

A stamp honoring Russian chemist Nikolai N. Zinin shows a warped version of aniline. U.S.S.R., 1962

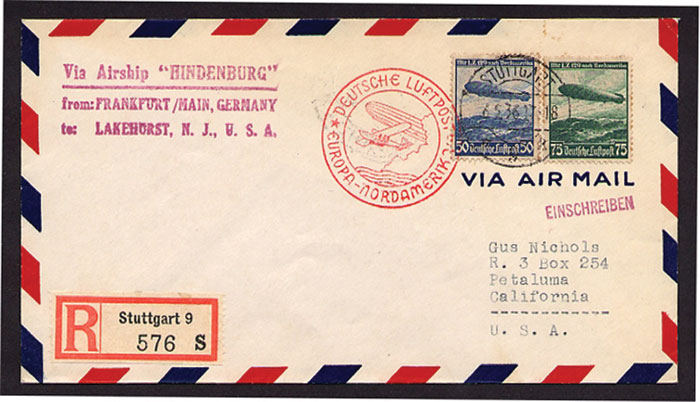

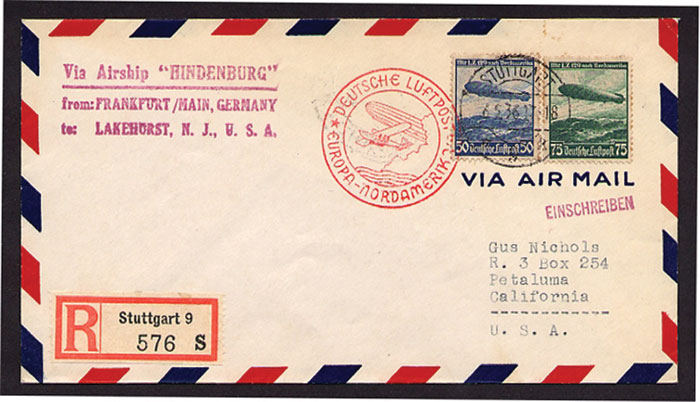

This cover was carried on the inaugural flight of the Hindenburg in 1936, a year before the zeppelin exploded and crashed in Lakehurst, N.J.

This cover was carried on the inaugural flight of the Hindenburg in 1936, a year before the zeppelin exploded and crashed in Lakehurst, N.J.

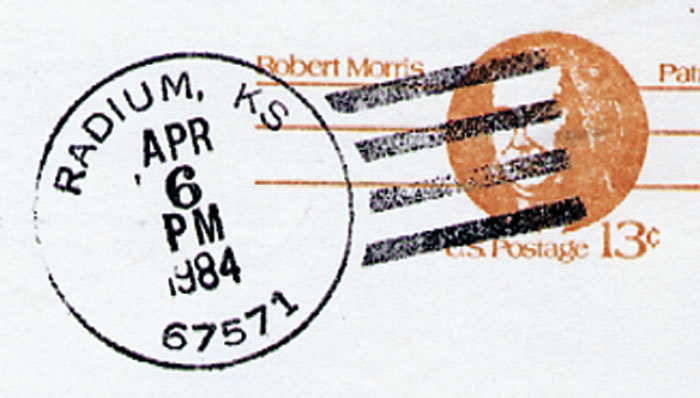

Postmarks with chemistry-related names include this one from Radium, Kan.

Postmarks with chemistry-related names include this one from Radium, Kan.

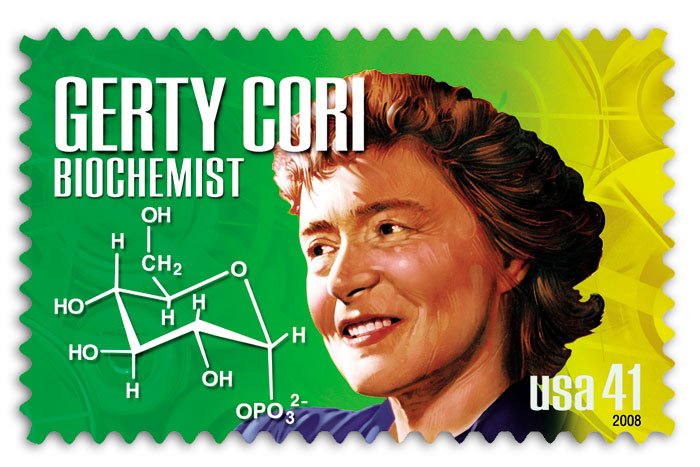

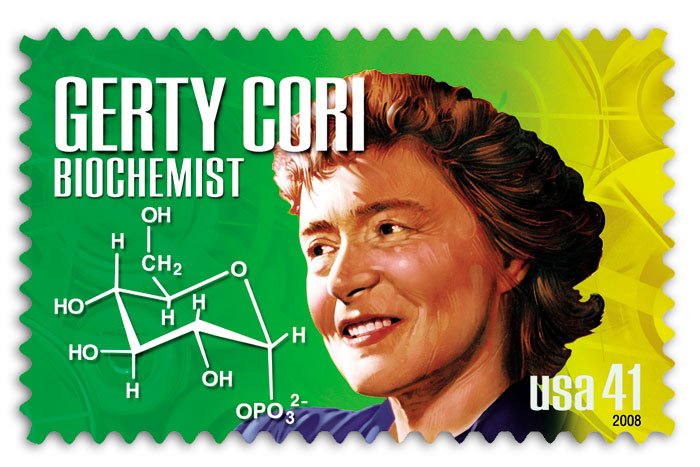

Next March, the Postal Service will issue a stamp honoring biochemist and Nobel Laureate Gerty Cori. U.S., 2008

Next March, the Postal Service will issue a stamp honoring biochemist and Nobel Laureate Gerty Cori. U.S., 2008

Depending on how broadly you define the category, you could obtain at least 2,000 such stamps from around the world, estimates Daniel Rabinovich, associate professor of inorganic chemistry at the University of North Carolina, Charlotte. The pursuit of chemical stamps is known as chemophilately, a term coined by Zvi Rappoport, an organic chemist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Rabinovich began stamp collecting when he was 10 years old. During high school, he narrowed his focus to particular countries, including Sweden, France, Great Britain, and his native Peru. After he decided to major in chemistry, Rabinovich began collecting chemistry stamps. His various collections consist of some 20,000–30,000 stamps and related philatelic materials, such as first-day covers, which are commemorative stamped envelopes released on the day the stamp is issued.

Another avid collector is Joseph Gal, an organic chemist who is a professor of medicine, pharmacology, and pathology at the University of Colorado, Denver. His scientific activities have centered on stereochemistry, particularly the role of chirality in the action and behavior of drugs.

Drawn by the history, culture, and politics displayed on stamps, he began collecting them as a child in Budapest, Hungary. His ardor cooled when he became a teenager, but he took up collecting again a decade ago.

"Suddenly it occurred to me how interesting it would be to connect work with stamps," Gal recalls. "I looked at my collection and there were a few stamps that were related to chirality, and then I started in earnest collecting stamps related to chirality."

Gal estimates that his total collection runs to about 10,000 stamps, first-day covers, and other philatelic artifacts.

Traditionally, countries issue postage stamps to celebrate anniversaries and historic figures, Rabinovich says. Some stamps, such as those featuring Disney or Star Wars characters, are issued just for entertainment. Occasionally, countries issue stamps related to science. "I guess they are not afraid to show science as a popular theme," he says. "They are not shy about the value of science, which may be a problem in the U.S. There are very few stamps in the U.S. related to chemistry."

The selection of chemists and discoveries that have appeared on stamps strikes Rabinovich as capricious and unpredictable. "Those of us who are chemists would have a different list, or a broader list," he says. In fact, he adds, "it's hard to believe that some countries will choose to put some obscure chemist, glassware, or molecules on stamps."

Historically, some countries, including the former Soviet Union and other nations in Eastern Europe, have had an ulterior motive for featuring chemistry, using the stamps as subtle propaganda for, say, their petrochemical or fertilizer industries, Rabinovich says.

Yet stamps can also "highlight some of the beauty of chemistry," he says. They can be used as a "way of communicating chemistry, which many people who are not even chemists appreciate."

Sometimes Rabinovich uses stamps to open a lecture. When he teaches his students about the inorganic chemistry of hydrogen, he shows them a stamped envelope flown on the Hindenburg's inaugural flight of 1936, a year before the famous zeppelin exploded and crashed in Lakehurst, N.J.

During the class, "I describe to the students the key physical and chemical properties of hydrogen, but they can have trouble memorizing these isolated facts," Rabinovich says. "If you show in class a picture of this cover, and tell them the story behind it, and they've heard of the Hindenburg and maybe seen movies, they will remember the properties of hydrogen."

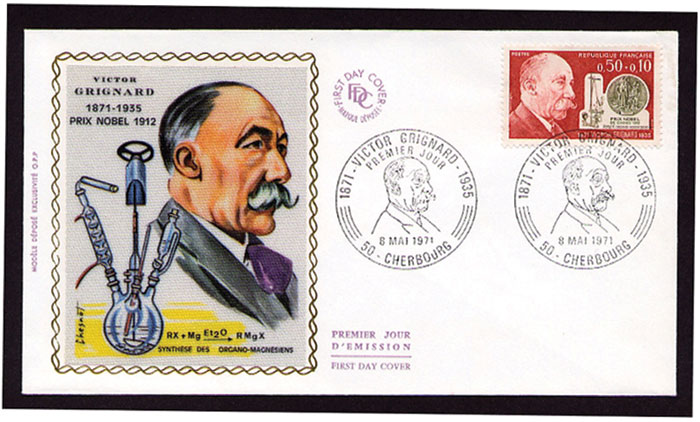

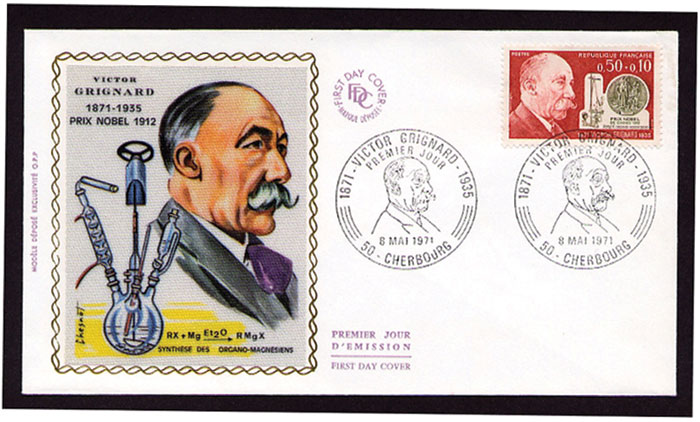

Last month he gave a talk during an American Chemical Society local section meeting at Juniata College in Huntingdon, Pa. There, Rabinovich showed the audience a French first-day cover honoring the famous chemist F. A. Victor Grignard. The cover shows the equation for preparing a Grignard reagent. "Students will remember that," he says. "They can't believe such detailed information would be on a philatelic souvenir prepared for the general public."

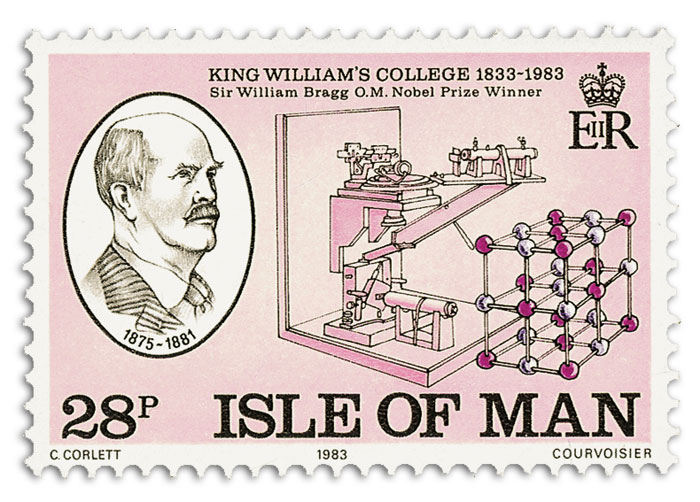

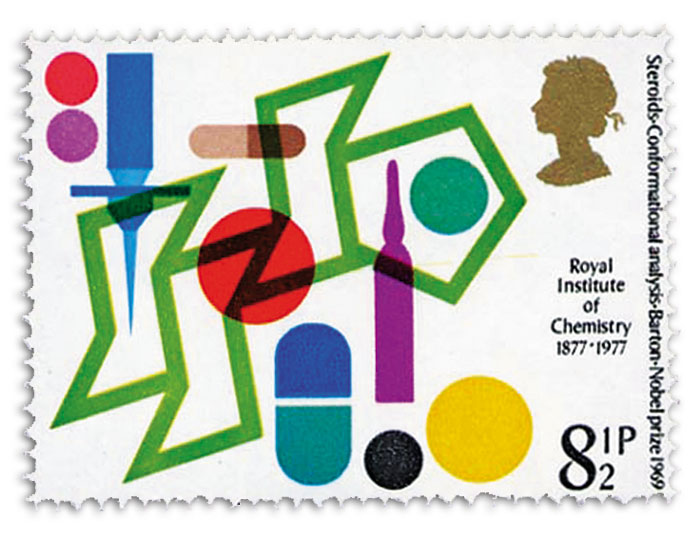

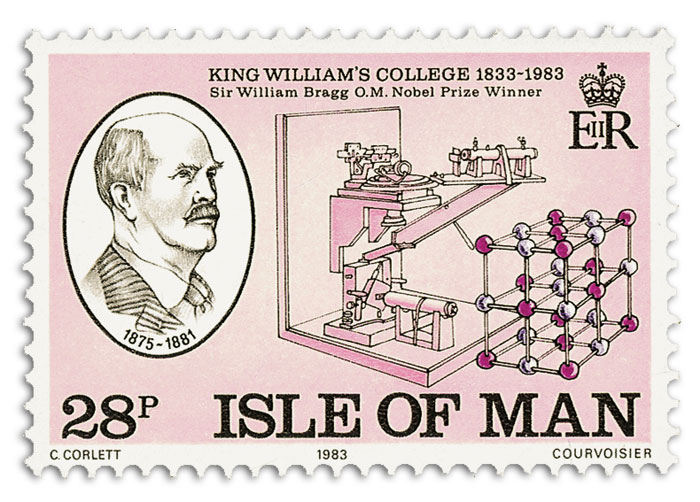

Even laboratory equipment can show up on stamps. The Isle of Man issued a 1983 stamp showing the English chemist, physicist, and mathematician William H. Bragg, who along with his son invented the technique for determining crystal structures using X-rays. A diffractometer and the crystal structure of NaCl accompany Bragg's portrait on the stamp.

Stamp designers can get quite creative in their use of chemistry. One of Rabinovich's favorite stamps was issued by the Soviet Union in 1965 for the 20th Congress of the International Union of Pure & Applied Chemistry. The design incorporates chemical symbols that spell out "Moscow" and "IUPAC."

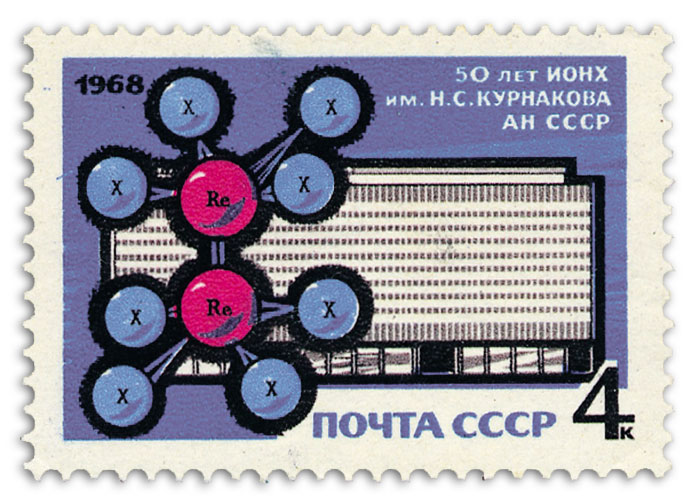

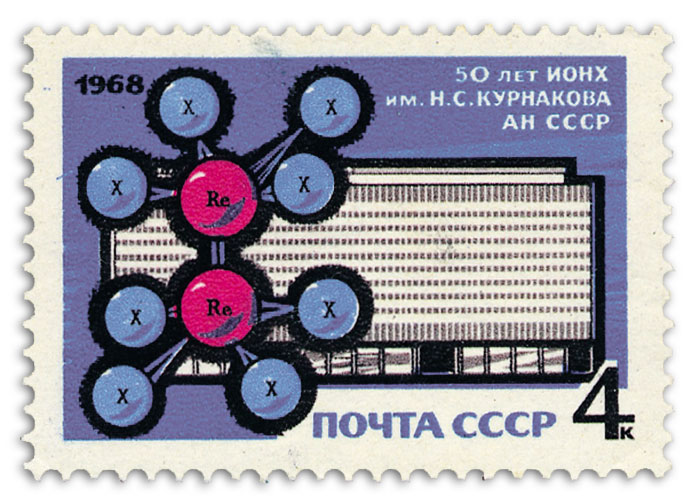

Another of his favorites was issued in 1968 by the Soviet Union on the 50th anniversary of the N. S. Kurnakov Institute of General & Inorganic Chemistry in Moscow. It shows Re2Cl82-, which was first synthesized at the institute and was reported in the 1950s. In 1964, F. Albert Cotton reported that the molecule contains a quadruple bond, the first ever detected.

Rabinovich particularly treasures one of his so-called maximum cards, which are stamped postcards typically illustrated with an image related to the subject shown on the stamp. Rabinovich obtained a maximum card prepared in Spain in 1983 on the 200th anniversary of the discovery of tungsten. He took the card to an ACS meeting and had the author and neurologist Oliver W. Sacks, who had recently published "Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood," autograph the card.

Gal's favorite chemistry stamp shows the French chemist and microbiologist Louis Pasteur with two nonsuperimposable mirror-image crystals of sodium ammonium tartrate. Pasteur discovered molecular chirality by using a microscope to separate a racemic mixture of these tartaric acid salts.

France issued the stamp in 1995 on the centenary of Pasteur's death. The stamp holds additional interest for Gal because after Pasteur's death, he "was built into a demigod, a lay saint, who was not only the most brilliant of scientists but was the ultimate good human being," Gal says. "That turns out not to be true. He had many human failings, and he fascinates me for that reason."

Failings aren't limited to the personalities of the people depicted on stamps. "As you can imagine," Gal says, "an awful lot of the stamps with chemistry or science have mistakes on them. The designers are artists, not chemists, and the postal service officials are not chemists, and they don't check enough with chemists."

Some of the errors are minor. A 1962 Soviet stamp showing the 19th-century Russian chemist Nikolai N. Zinin, who was the first to reduce nitrobenzene to aniline, depicts a somewhat warped structure of the molecule.

Other errors are more flagrant. Sweden sought to honor its 18th-century chemist and pharmacist Carl W. Scheele, and yet it failed to do so. "Experts agree that it's not Scheele but his nephew who's on the stamp," Gal says.

Monaco tripped up in multiple ways when it created an attractive stamp to highlight the plastics industry, "which as far as I know is not really big in Monaco," Rabinovich says. "To represent the industry, they show a molecule of methane—which is not really used for making plastics—being transformed into gasoline or hydrocarbon. But instead of CH4, they show the molecule as HC4."

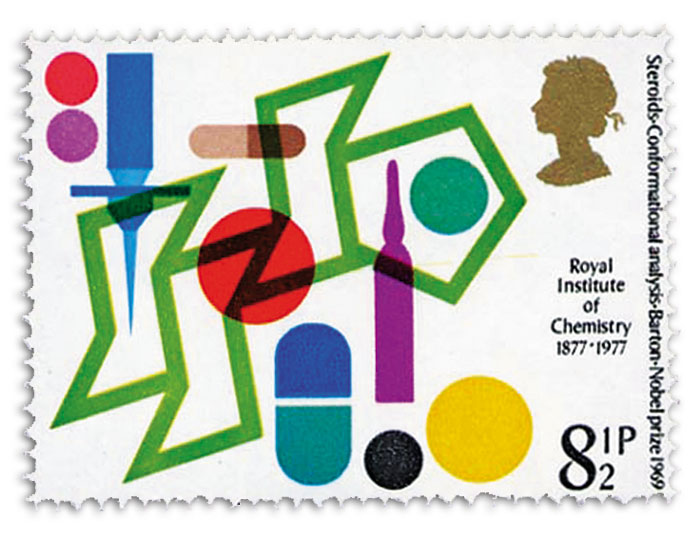

On the other hand, Gal says, there are a few outstanding examples of accurate chemistry in stamps, including a 2005 Austrian souvenir sheet that contains a stamp honoring native son Carl Djerassi. The sheet features his portrait and enantiomeric steroid molecules—with correct stereochemistry, Gal notes—in honor of Djerassi's work with steroid chemistry and the development of the birth control pill. Djerassi's stamp was also notable because it helped mark his reconciliation with the country that had expelled him in 1938.

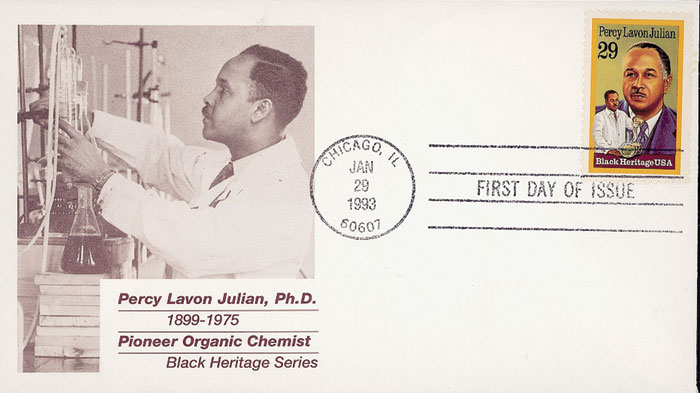

Other stamps help to redress prior wrongs. For instance, a 1993 U.S. stamp depicts chemist Percy L. Julian, whom Gal describes as a "truly inspiring figure. A black American, he succeeded in obtaining a doctorate despite discrimination. Discrimination prevented him from getting an academic position in the U.S., but he still became a highly successful and accomplished chemist."

Other U.S. stamps that commemorate scientists with ties to chemistry include a 1981 issue for Rachel Carson, whose book "Silent Spring" warned of the health and environmental dangers of synthetic chemical pesticides.

In 1983, the U.S. issued a stamp honoring Joseph Priestley. Born in England in 1733, Priestley immigrated to America in 1794 after his vocal support for the American and French revolutions made him a persona non grata. Priestley was a Unitarian minister whose experiments with gases led to his discovery of oxygen.

A 2005 stamp shows J. Willard Gibbs, who was instrumental in developing the subject of thermodynamics. A mathematician and theoretical physicist and chemist, he was born in 1839 in New Haven, Conn., and is associated with such concepts as Gibbs free energy and the Gibbs-Helmholtz equation.

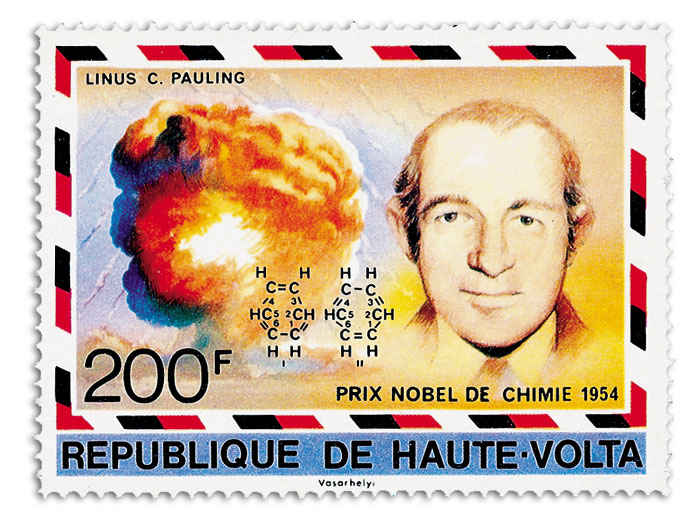

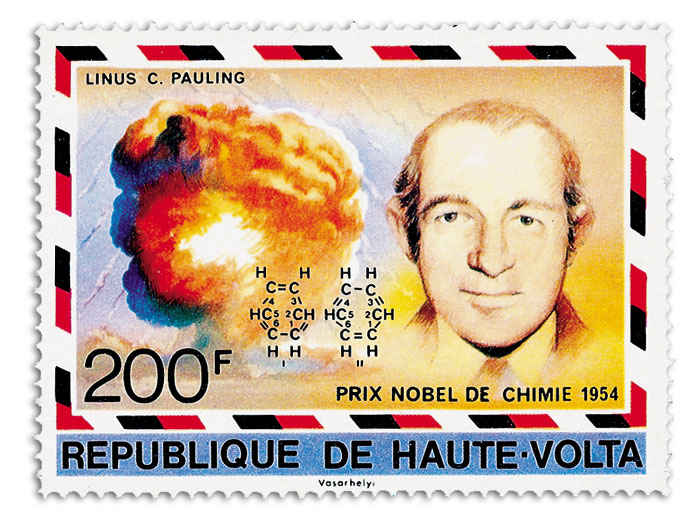

Next March, the U.S. will issue four stamps honoring American scientists, including biochemist Gerty T. Cori and structural chemist Linus C. Pauling. The 41-cent stamps feature portraits of the scientists and illustrations representing their major contributions.

Cori and her husband, Carl, "made important discoveries—including a new derivative of glucose—that elucidated the steps of carbohydrate metabolism and became the basis for our knowledge of how cells use food and convert it into energy," according to the Postal Service. "Their work also contributed to the understanding and treatment of diabetes and other metabolic diseases." The couple won the 1947 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Pauling "determined the nature of the chemical bond linking atoms into molecules," the Postal Service notes. "He routinely crossed disciplinary boundaries and made significant contributions in several diverse fields. His pioneering work on protein structure was critical in establishing the field of molecular biology and his studies of hemoglobin led to many findings, including the classification of sickle cell anemia as a molecular disease."

Pauling won the 1954 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his fundamental studies of chemical bonding and the 1962 Nobel Peace Prize for his campaign against nuclear weapons. Gal notes these two interests were combined in a dramatic stamp issued by Upper Volta in 1977, complete with benzene rings and an atomic explosion.

Some major chemists have never appeared on stamps. For instance, Gal believes a stamp for England's William H. Perkin is long overdue. While seeking a way to synthesize quinine in 1856, Perkin accidentally made mauveine, the first successful synthetic dye. This discovery and Perkin's subsequent work helped launch the modern chemical industry, Gal says.

Rabinovich points out that the American chemist Gilbert N. Lewis, known for Lewis acids and bases and for Lewis dot structures, has also been neglected.

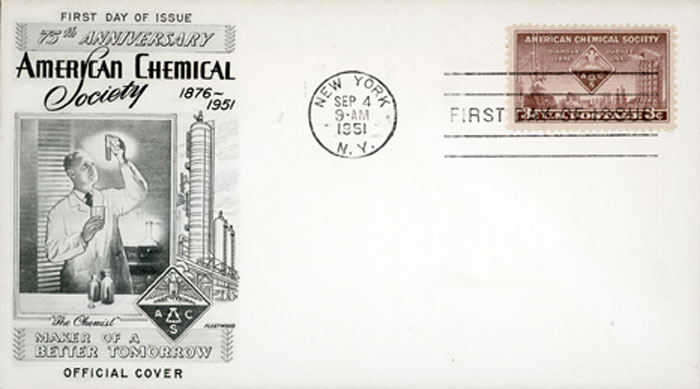

Of course, chemistry-related stamps aren't limited to biographical subjects. The Postal Service issued a 3-cent stamp commemorating the ACS's 75th anniversary in 1951 and a 13-cent stamp in conjunction with the society's 100th anniversary in 1976.

Chemistry can even show up in postmarks, Rabinovich notes. These postal markings are printed on a letter or package to indicate the date and time of mailing and the name of the city from which the item is mailed. Chemistry-related postmarks include Boron, CA; Bromide, OK; Neon, KY; Potash, LA; Radium, KS; and Telluride, CO.

"There's chemistry all around us," Rabinovich says.

- Chemophilately

- Chemistry stamps depict key discoveries, famous chemists, and chemical errors

- Stamp Data

- Magazine articles, stamp club, and the 'bible' provide wealth of resources

- Stamp Backstory

- The inner workings of the Postal Service

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter