Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Destroying VX

Activists fear the Army's 1,000-mile shipments of neutralized VX wastewater may be endangering the public and environment

by Lois R. Ember

March 24, 2008

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 86, Issue 12

TWICE PER WEEK, three-truck convoys roll down the interstate highways of eight states carrying wastewater from the neutralization of VX nerve agent.

The convoys begin in Newport, Ind., where the Army takes the first step in destroying the deadly chemical. They travel nearly 1,000 miles, passing through Memphis, Tenn., and Baton Rouge, La., to a federally approved hazardous waste disposal facility in Port Arthur, Texas.

Once at the Texas facility, the wastewater—or hydrolysate as the Army calls it—is pumped into holding tanks to await incineration, and the trucks are released to make the return trek to Indiana.

Transporting the VX hydrolysate (VXH) has raised the hackles of environmental and citizen activists who have sued the Army to halt the practice and to treat VXH in an on-site secondary treatment facility at Newport.

Although the Department of Transportation and the affected states have approved the transport of VXH, the activists maintain that under the terms of the Chemical Weapons Convention, VXH is still a chemical weapon. Their argument flows from the fact that under the treaty the U.S. receives no credit for destroying VX until VXH undergoes secondary treatment—in this case incineration at Veolia Environmental Services' Port Arthur facility.

As a chemical weapon, VXH is barred by federal law from being shipped across state lines. And when shipped, it could endanger people and the environment, they argue.

The Army counters that VXH is merely a caustic hazardous waste formed when VX is neutralized with sodium hydroxide. As such, it is no more dangerous than other hazardous waste commonly shipped across the country.

The Army makes this claim based on methodology it uses to test for residual VX and a by-product of hydrolysis called EA 2192 in the VXH produced. Activists claim the methodology is flawed, and the Army has been particularly vague on whether it was developed using standard Environmental Protection Agency methods and procedures.

At any rate, the Army has pledged not to ship any hydrolysate containing VX (O-ethyl-S-[2-(diisopropylamino)ethyl] methylphosphonothiolate) and EA 2192 {S-[2-(diisopropylamino)ethyl]methylphosphonothioic acid} above certain so-called nondetect levels. For VX, that level is now less than or equal to 9 parts per billion, much lower than the previous limit of less than or equal to 20 ppb. For EA 2192, it is less than or equal to 200 ppb, again lower than the previous limit of less than or equal to 1 part per million. The Army measures the two compounds using a gas chromatograph-ion trap mass spectrometer.

The hydrolysate contains about 70–85% water and 15–30% phosphorus- and sulfur-containing organic salts that partition into aqueous and organic layers. The Army measures, without explanation, only the aqueous layer for VX and EA 2192.

In their lawsuit the activist-plaintiffs assert that the Army is using an incorrect analytical method to measure residual VX and that more VX may remain in the hydrolysate than the Army contends.

IN A MOVE to shorten the legal process, the plaintiffs filed a preliminary injunction motion in May 2007 to halt VXH shipments. And they, to no avail, have also asked EPA to look into the Army's methodology to determine whether what is moving across the nation's highways is really safe.

As a party to the chemical weapons treaty, the U.S. must destroy its 30,000-ton chemical arsenal, including the 1,269 tons of VX nerve agent stored in bulk at Newport, by 2012. The Army began neutralizing Newport's VX in May 2005.

The Army could have destroyed the VXH formed by neutralization in a supercritical water oxidation (SCWO) unit that it could have built on-site. Such an approach was approved by Indiana citizens and officials and endorsed by the activists. Instead, after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, the Army argued that it would be faster and cheaper to neutralize the agent on-site and transfer the wastewater off-site for secondary treatment at an existing facility.

In 2003, the Army tried to ship the hydrolysate to a treatment facility in Ohio. Strong citizen opposition and subsequent lawsuits, however, forced the Army to back away from that plan.

The following year, the Army tried moving forward by selecting a DuPont plant in New Jersey as its off-site treatment facility. But opposition from officials from several affected states and their citizenry, along with well-organized environmental groups and a federal lawsuit, forced DuPont to bow out in January 2007.

As it searched for secondary treatment facilities, the Army developed an on-site storage plan for the VXH being produced. Among the accumulating stores of VXH were the first 24 batches, which proved to be more flammable than the Army had anticipated.

Because they have the potential to ignite at relatively low temperatures, these early batches can never be shipped across state lines. They will have to be neutralized again at a later date.

The flammability problem forced the Army to tweak its neutralization process, and the now-shippable VXH inventory at Newport began to build. With the flammability problem eliminated and approval from EPA and the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention to ship VXH off-site, the Army still needed to find a secondary disposal site.

Not only was the Army contending with the history of fierce public opposition to transporting VXH off-site, but its on-site storage space was rapidly filling up. So the Army opted for a behind-the-scenes tack.

With no public notification, in early April 2007, the Army signed a $49 million contract with Veolia Environmental Services to incinerate VXH at its Port Arthur facility. Veolia's incineration facility is permitted under the Resource Conservation & Recovery Act (RCRA) to burn hazardous waste.

As a federally licensed hazardous waste facility, the Veolia incineration plant is required to monitor its stack emissions for many constituents "but not VX," acknowledges Mitch Osborne, the plant's general manager.

Osborne says it is not necessary for the facility to monitor for VX emissions. He bases this on the Army's many years of experience with destroying VX at its own facilities such as the one in Tooele, Utah, and on the Veolia incinerator's destruction and removal efficiency of 99.99999% for compounds such as 1,2-dichlorobenzene, a surrogate for organophosphorus compounds like VX. "We are assuming the efficiency of our unit will destroy any VX in the hydrolysate before it exits our stack," he says.

The Veolia facility is located in a low-income minority community that was never made aware of the pending contract until it became public knowledge. The citizen and environmental groups involved in the litigation cite the lack of prior notice as a violation of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).

Port Arthur residents learned of the contract on the night of April 16, 2007, when the first convoy of four tanker trucks, each carrying one container holding about 4,000 gal of VXH, left Newport for Port Arthur. The Army initially planned to send 12 trucks per week on the 1,000-mile trek, but currently only six trucks per week are making the journey.

A month after the first convoy, the Sierra Club, the citizens' group Chemical Weapons Working Group (CWWG), the Community In-Power Development Association, and others filed a lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Indiana to stop the shipments. Such shipments, they argued, violate state and federal laws.

According to CWWG Director Craig E. Williams, the plaintiffs, in their preliminary injunction filing, argued that the trucking of VXH poses imminent risks to public health and the environment because VXH is more dangerous than the Army has claimed. The plaintiffs asserted that the Army was performing inadequate analyses of the VXH for residual VX nerve agent and other by-products of hydrolysis, such as the toxic compound EA 2192, and thus their levels in the transported VXH might be higher than the Army asserts.

Michael A. Sommer II, a forensic environmental chemist and expert witness for the plaintiffs, wrote in the declaration he submitted to the court, the "Army's GC-MS method completely ignores numerous reaction products and naively assumes that only VX and EA 2192 are in the hydrolysate mixture. Many of these reaction products are highly toxic."

At the preliminary injunction hearing, Peter M. Racher, a Veolia attorney, proclaimed that the plaintiffs' concern about the shipments was "an irrational fear based on nonscience."

IN THEIR FILING, the plaintiffs also argued that there was no way of determining if VXH had been completely combusted or if toxic emissions, such as VX, were being released to the air because Veolia has no stack monitors capable of making such determinations. In contrast, incinerators at sites where the Army stores and destroys VX, such as the one in Anniston, Ala., have devices on stacks that can monitor for VX emissions.

Additionally, the plaintiffs contended that there is evidence from the Army's own data that VX may be re-forming in the containers in which VXH is stored before being shipped to Texas for incineration.

During the hearing, Army officials discounted VX re-formation theories. They cited a 2000 National Research Council report that concluded VX cannot and does not re-form in hydrolysate that contains excess sodium hydroxide (4%). The VXH stored on-site contains such excess base.

The citizens groups had considered filing a motion for a temporary restraining order to halt VXH shipments before the preliminary injunction could be heard and ruled on by U.S. District Judge Larry J. McKinney. Instead they opted to ask the Army to do so voluntarily, and in June, the Army halted shipments.

During the lull in shipments, Army spokesman Gregory Mahall repeatedly stressed the Army's belief that the hydrolysate is safe and its shipment violates no laws. He pointed to the more than 100 shipments that had occurred without mishap from April, when shipments began, to June, when they stopped.

While shipments were temporarily suspended, the Army continued to neutralize VX and store the resulting VXH on-site.

The Army's voluntary suspension ended on Aug. 3, 2007, when Judge McKinney issued his order denying the plaintiffs' motion for a preliminary injunction. "A preliminary injunction is an extraordinary remedy that will only issue on a clear showing of need," McKinney wrote. "In order to obtain a preliminary injunction, plaintiffs must show a likelihood of success on the merits, irreparable harm if the injunction is denied, and the inadequacy of any remedy at law."

He based his decision on the first standard. "The court concludes on the record before it that plaintiffs have failed to show a likelihood of success on the merits of their claims" that VXH shipments violate NEPA, RCRA, the Defense Authorization Act, or Indiana and Texas RCRA-related laws, he wrote. Because of this failure, he said, it was not necessary for him to discuss the remaining two factors.

After McKinney's denial, the plaintiffs had several legal recourses open to them, including asking McKinney to reconsider his order. Ultimately, they decided "to move forward on the merits of the entire case in a full-blown trial" in McKinney's court, CWWG's Williams says.

With the full trial many months off and VXH shipments having resumed, the plaintiffs once again sought to block them by filing a summary judgment motion in McKinney's court last October. In an agreement with the Army, the plaintiffs narrowed the summary judgment to NEPA issues, thus postponing any action on RCRA issues for later litigation.

Flush Out

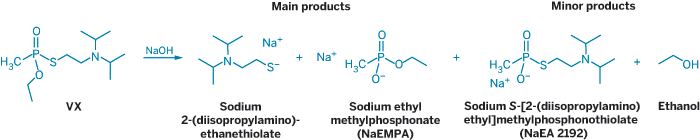

Caustic neutralization of VX yields several toxic products, but the Army measures so-called hydrolysate only for residual VX and EA 2192.

In their summary judgment filing, the plaintiffs argued that the Army failed to fulfill its NEPA obligations by holding no public process on transportation and treatment issues and by not considering environmental justice issues, Williams says. But more important, he adds, the Army withheld relevant documents from the administrative record whose contents should have been argued during the preliminary injunction motion.

WHEN PRESSED by plaintiffs, the government ultimately amended the administrative record to include more than 40 additional documents. Among those were some "that proved that the viability of an on-site treatment of the hydrolysate, SCWO, was known to the Army and was selected by the Army should the New Jersey shipment option fail. And it did fail," Williams says. "We believe the Army in February 2007 made the arbitrary decision to ship the stuff" to Texas, he says.

Advertisement

One of the RCRA issues in abeyance until McKinney rules on the summary judgment is the correctness of the method—called the method of standard additions—the Army now uses to determine the concentration of VX and EA 2192 in the hydrolysate.

During the preliminary injunction hearing, Robert L. Irvine, a Ph.D. chemical engineer, testified on this new method, which the Army terms the "modified method." Irvine is chief scientist for the Army's contractor, Parsons Corp., and an executive in his own company, SBR Technologies.

Irvine and his staff spent 11 months reviewing the modified method and concluded that it is "inappropriate" and "flawed." In his report, Irvine concluded that this method not only underestimates VX levels and produces false negatives, it also does not reduce the likelihood of false positives, which the Army thought the original test method was producing.

In his report Irvine concluded the Army should not use the modified method, a recommendation the Army didn't follow.

According to Army spokesman Mahall, "The change in procedure was initiated by Parsons to deal with matrix issues in the previous testing method that were thought to be leading to what were assumed to be false positives." The matrix issues Mahall mentions refer to effects on the analysis by components of the hydrolysate other than VX or EA 2192. The modified method was initiated because the Army thought it to "be more reliable," he says.

In his testimony at the preliminary injunction hearing, Irvine reversed himself. He said that, at the Army's request, CDC had reviewed the Army's testing data and his report and had concluded that the Army's modified method is an appropriate one to use. CDC recommended that the Army implement the modified method and, on the basis of CDC's approval, Irvine testified that his concerns about the method were allayed.

C&EN attempted to speak with Irvine to probe him on his reasons for not standing by his report's original conclusions. He begged off taking questions several times.

Irvine was incorrect in testifying that CDC had reviewed his report. According to Mahall and John Decker, a supervisory scientist in CDC's chemical weapons demilitarization program, CDC never saw Irvine's report. "We have not been able to locate any such report in our files, nor have we been able to identify references to that report in other documentation" that the Army supplied, Decker tells C&EN.

It was never clear from interviews with Decker just what data CDC received from the Army for review. Were they, for example, a subset of all the data generated, chosen because they indicated residual VX at levels below the 9 ppb nondetect threshold? Or were they all the data generated from analyses of hydrolysate from all neutralization runs? Decker says only that CDC reviewed the Army's "test plan" and analyzed "actual data generated" by the Army with the modified method.

CDC did no independent testing. Or as Decker says, "CDC did not duplicate the tests." On the basis of an analysis of Army-generated data, CDC concluded that "the modified method represents an improvement over the original method because the modified method better accounts for the effect of the matrix," Decker says.

During the preliminary injunction hearing, plaintiffs' expert witness Sommer testified that the modified method will not yield a valid or reliable indication of the actual concentration of VX in the hydrolysate.

Sommer says that "under RCRA, EPA has specified test methods to be used to demonstrate that any waste is not toxic." He says the Army used an inappropriate test method for organophosphorus compounds and then used the method of standard addition calibration applied to GC-MS.

A witness for the Army, William G. Kavanagh, testified that the method the Army developed had never been the EPA standard method; rather, it was one that had been developed in cooperation with EPA for testing for nerve agents.

In an August 2007 letter to EPA Region VI, Sommer asked the agency to look into the Army's method, which he believes is "wholly inadequate." In court he testified that the modified method is not an EPA method and is "thoroughly not appropriate for this kind of determination."

VX Destruction StatusAs Of March 18

1,269 tons of VX originally stored at Newport, Ind.

1,060 tons of VX neutralized, 84% of the Newport stockpile

300 containers of neutralized VX wastewater (hydrolysate) shipped to Port Arthur, Texas, for incineration; eventually a total of 450 will be shipped

1,076,538 gal of hydrolysate shipped to Texas

1,055,118 gal of hydrolysate incinerated in Texas

891 tons of VX destroyed under terms of chemical weapons treaty

Two months later, an EPA official answered Sommer's letter. In his reply, Carl E. Edlund, director of Region VI's Multimedia Planning & Permitting Division, wrote that his group had contacted the Army's litigation center "to obtain more information on the analytical method." Edlund wrote that the Army had informed him that it was unable to supply EPA with information to evaluate the modified method "because the VX test method and other issues are still being litigated."

C&EN asked Edlund whether EPA had any authority to force the Army to release the information so his agency could assess the methodology's accuracy, as Sommer had requested. His answer: EPA and the Army "have the same Department of Justice lawyers, and you can't have one part of the government testifying for the good doctor [Sommer] in a suit against another part of the government." He did say, however, that "the technical merits of Sommer's concerns are being evaluated."

EPA OFFICIALS would not address C&EN's questions about the appropriateness of the modified method to measure residual VX and EA 2192 in the hydrolysate. Troy Hill, associate director for Region VI's Multimedia Planning & Permitting Division, says the hydrolysate "is being handled properly under RCRA." Veolia, he says, is a RCRA-compliant facility that is permitted to handle corrosive waste. Veolia is not permitted to handle VX, however.

"If the Army was saying that the hydrolysate was not hazardous, and we believed that it had the potential to be hazardous, then we would look into it, Hill says. "But, the Army is saying it is hazardous, and we believe it is being properly characterized and handled as a hazardous waste."

Hill continues: "If we felt the hydrolysate posed a higher risk, EPA has enforcement authority that could be used" to force the Army to release data. But "at this point," he says, "EPA feels the hydrolysate is being properly handled as a hazardous waste."

Sommer believes the activists' best recourse now is to file a motion "to compel EPA to do its job." According to him, "EPA has the authority to require the Army to follow EPA test methods; EPA needs to enforce its own rules."

The terms of an agreement limiting the summary judgment motion to NEPA issues do not permit the plaintiffs to file a separate RCRA-related motion to compel EPA to evaluate the Army's test methods. But other activists are not barred from taking action, and citizen groups and their attorneys in Texas are considering filing a separate motion focused on RCRA issues that could prod EPA into acting.

All of this convoluted legal wrangling may end up being moot. According to Army spokesman Mahall, the Army "should complete neutralization of the VX by late summer. And incineration of the hydrolysate at Port Arthur should be completed shortly after the last batch of hydrolysate is produced."

BY MARCH 18, the Army had neutralized nearly 84% of the VX stored at Newport. According to Mahall, total cost for destroying the 1,269 tons of VX at Newport will approach $1.5 billion.

A full-blown trial on the merits of the issues previously argued cannot begin until McKinney rules on the summary judgment, which at press time he had not done. Mahall says government lawyers "are shooting for a November trial date," several months after destruction of VX is likely to be completed.

If McKinney denies the plaintiffs a summary judgment to halt shipments, the full trial "will not happen," Williams says.

Trial or not, if the plaintiffs' concerns have factual bases, the Army, by possibly using an inappropriate test method, may be mischaracterizing the hydrolysate as a caustic hazardous waste instead of a chemical weapon. If the plaintiffs are correct, the Army may be in violation of RCRA. But without EPA's independent evaluation, this may never be known.

The shipments of hydrolysate have so far occurred without mishap. Whether higher levels of VX than the Army purports to measure in the hydrolysate are traveling the highways may forever remain a mystery.

Veolia's incinerator may be releasing some VX and combustion by-products such as dioxins to Port Arthur's ambient air, as the plaintiffs fear. But this, too, will never be known because Veolia is not required by its RCRA permit to monitor its stack for such compounds.

If the plaintiffs are correct, the public and the environment may unwittingly have been put at risk of exposure to some of the most toxic and lethal chemical substances ever devised.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter