Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Chemical Killing

Controversy continues over lethal injection drugs despite recent Supreme Court decision

by William G. Schulz

May 19, 2008

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 86, Issue 20

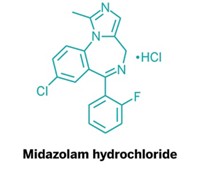

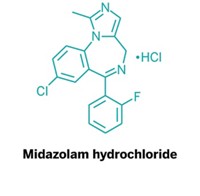

THE RECENT Supreme Court decision regarding lethal injection in Kentucky upheld the procedure as constitutional, but it's unlikely that the controversy surrounding this method of execution will diminish anytime soon. Problems with the lethal three-chemical injection—sodium thiopental, pancuronium bromide, and potassium chlorate—that is used in nearly every state with a death penalty will continue to be the focus of lawyers representing condemned inmates, judges who hear death penalty challenges, death penalty abolitionists, and other activists.

Meanwhile, executions are moving forward. On May 7, the State of Georgia executed William Earl Lynd by lethal injection, the first since the high court's April 16 decision.

The controversy about lethal injection stems in part from a dearth of toxicological studies on the three-drug protocol. Scientists disagree about the effectiveness of the protocol in rendering an inmate unconscious for the whole of the procedure. The risk that an inmate might be conscious and thus experience excruciating pain from the procedure was at the heart of the Supreme Court case. Ultimately, the Court decided that the risk did not rise to a level that violates the Eighth Amendment prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.

The lethal injection protocol was concocted in the 1970s by an Oklahoma medical examiner. The Oklahoma Legislature adopted the procedure in 1977, and other death penalty states soon followed suit. Lethal injections are now carried out by the federal government and by 36 states with the death penalty. Because of its perceived humaneness, lethal injection has largely replaced electrocution, lethal gas, and other execution methods.

Indeed, lethal injection appears to be a painless, medicalized procedure to end human life. But medical professionals are rarely involved in lethal injections, because doctors and nurses are prohibited by their professional associations from participating in executions. Instead, lethal injections are most often carried out by corrections department personnel who don't always have training in setting intravenous lines or mixing and delivering the drugs.

Studying the drugs' effects postmortem is complicated by the fact that toxicologists have had limited access to blood samples, which could harbor signs about whether the lethal injection worked as intended.

"Lethal injection is not what the public and many lawmakers think it is—a serene and soothing way to die, like putting a sick animal to sleep," Fordham University professor of law Deborah W. Denno writes. She has studied and written extensively about lethal injection, a process she considers "inhumane and tortuous." She says states are so secretive about their lethal injection protocols, including amounts of the drugs given, that it is nearly impossible to determine whether executions are in fact being conducted humanely.

"You couldn't euthanize an animal the way they use these chemicals on people," Denno says. She is referring to the fact that in veterinary euthanasia procedures, most often only barbiturates are used to induce death. In lethal injection of prisoners, however, sodium thiopental is given first to anesthetize the condemned inmate; followed by pancuronium bromide, a paralytic agent; and last, potassium chlorate, which stops the heart by interfering with electrical signaling.

"PROBLEMS with the chemicals have always been there," Denno says.

That the first drug, sodium thiopental, may not be an effective anesthesia as administered raises concerns about the use of pancuronium bromide, says Susi Vassallo, a medical toxicologist at New York University School of Medicine. She recently participated in a symposium on lethal injection at Fordham Law School in New York City that explored some of the medical issues. She says the problem with the paralytic agent is that it renders the inmate incapable of indicating consciousness before the third, heart-stopping drug is delivered. If still conscious, then the inmate may be subjected to intense burning sensations and excruciating pain before dying.

"There may be a lot of suffering that goes unrecognized," Vassallo says.

Very little scientific data are available to determine whether inmates suffer, however. In one postmortem study of 49 inmates' blood taken from inmates after lethal injection, the authors found that "postmortem concentrations of thiopental in the blood were lower than that required for surgery in 43 of 49 executed inmates (88%)." What's more, the scientists found that "21 (43%) inmates had concentrations consistent with awareness" (Lancet 2005, 365, 1412).

The paper "stands as the best peer-reviewed data on the subject," says coauthor Leonidas G. Koniaris, an associate professor of surgical oncology at the University of Miami Medical School. He agrees that the data are limited but says the data are valid.

Other researchers are less sanguine about the paper. "Koniaris and colleagues do not present scientifically convincing data to justify their conclusion that so large a proportion of inmates have experienced awareness during lethal injection. Indeed, published and unpublished data and clinical experience contradict their conclusions," write Mark J. S. Heath, a professor of anesthesiology at Columbia University; Donald R. Stanski, an anesthesiologist at Standford University School of Medicine; and Derrick J. Pounder of the University of Dundee, in Scotland, in a letter responding to the postmortem blood-analysis report (Lancet 2005, 366, 1073).

"It is widely accepted that concentrations of a drug in postmortem blood might not reflect the concentrations present at the time of death because of postmortem drug redistribution—i.e., site-dependent and time-dependent changes in drug concentration that occur after death," Heath and colleagues point out in their letter.

Nonetheless, Heath tells C&EN he believes that the lethal injection protocol is problematic. He even provides expert testimony for plaintiffs in court. Heath says the problems include the assigning of unqualified individuals to insert the execution needle into the prisoner's vein, poor supervision of intravenous drug delivery systems, and poor control over the timing and sequence of drug delivery.

Vassallo points out another major shortcoming of postmortem blood analysis. "It doesn't reflect the activity of the brain—it can never show that," she says.

"THE PRIMARY QUESTION is whether the inmate is reliably unconscious when thiopental is administered," Vassallo says. "When it comes down to the chemistry, however, there are no studies of thiopental administration in these doses," she says. "If you give a large dose of thiopental, will you have unconsciousness? It's not clear that that's supported."

Denno and others say the extensive record of botched lethal injection executions indicates the problems with the entire procedure, especially rendering inmates unconscious. They say there are cases in which inmates have either woken up during the procedure or never became unconscious in the first place; cases in which postmortem exams have indicated that the drugs, including the anesthetic, were not delivered venously, resulting in severe burns to tissue surrounding the injection site and possibly also in inadequate anesthesia; and cases in which the drugs had to be administered multiple times to kill the inmate. Moratoria on lethal injection executions in states such as Florida and California, they say, prove that the problems are real.

In California, U.S. District Court Judge Jeremy Fogel decided that the state's "implementation of lethal injection is broken, but it can be fixed." In 2006, he halted an execution so that the state could review and revise its lethal injection protocol. It was a landmark case in which a federal judge found that the risk of subjecting an inmate to excruciating pain via a botched lethal injection violated the Eighth Amendment prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.

"The constitutional issue raised by lethal injection cases is not simply explained or easily understood," Fogel has written. "Compared to earlier methods of execution, lethal injection may appear to be nothing like the 'cruel and unusual punishments' prohibited by the Eighth Amendment. Understanding the claim requires knowledge of the physical effects of each of the chemicals used, the ways in which the execution process is subject to human error and the points at which there is a nonspeculative potential for such error, and the medical significance of data obtained from the bodies of condemned inmates during and after their executions."

Following Fogel's ruling, California reevaluated its protocol and made changes to address the objections. Once the state adopts its new protocol, the judge will review it to determine whether it meets the standards set by the Supreme Court before allowing lethal injections to resume.

But some experts contend that existing lethal injection protocols are humane. "If the protocol is done as written, the inmate will not suffer," says Mark Dershwitz, a professor of anesthesiology at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. He says the pharmacology and pharmacokinetics of the three drugs used in lethal injections are well understood and established through peer-reviewed studies. But he also reminds people that "lethal injection is not a medical procedure in the first place."

Dershwitz often testifies for states in lethal injection challenges. He says he takes no public position on the death penalty; rather his interest is in the science. He says one of his research interests is preventing awareness under anesthesia, and the controversy surrounding lethal injection touches upon this area of expertise. "We should exclusively confine ourselves to the science," he says. And for Dershwitz the science supports the idea that lethal injection induces a pain-free death.

In the end, Vassallo notes wryly, "the three-drug protocol is efficacious—everybody dies."

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter