Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

Drugs At The Starting Line

The Olympics begin with new antidoping lab and measures to keep athletes honest

by Marc S. Reisch

August 11, 2008

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 86, Issue 32

MORE THAN 10,700 ATHLETES are expected to compete in 302 events covering 28 different sports during the Games of the XXIX Olympiad now under way in Beijing. Held Aug. 8–24, the Games will raise billions of dollars for the International Olympic Committee (IOC) through product licensing and sponsorship arrangements, ticket sales, and broadcast rights. Only about $10 million of that sum will be spent on testing athletes for performance-enhancing drug use.

Olympic officials have long sought to prevent doping, whereby athletes inject or ingest drugs to give them an edge in their quest for gold medals and world records. But preserving the ideal of athletes competing only with physical strength, skill, and endurance continues to be a major difficulty that depends on the skills of analytical scientists and the budget for drug-testing instruments.

The Olympics is "the most intense period of analytical testing on Earth," says Don Catlin, an antidoping pioneer who in 1982 founded the Olympic Analytical Laboratory at the University of California, Los Angeles, the first U.S. antidoping lab. The lab set up at the Beijing Olympics will run around the clock to analyze urine and blood samples and report results between 24 and 72 hours after they are processed. "The name of the game is to find drugs," says Catlin, one of the senior antidoping experts at the Olympic lab who ensure that technicians scrupulously follow test protocols.

Despite the publicity about testing, a number of sports doping scandals have overshadowed the current Games. Just days before the start of the Games, seven Russian athletes were suspended by track-and-field authorities for subverting antidoping efforts.

Late last year, U.S. track-and-field champion Marion Jones was convicted and sentenced for lying to investigators about taking the "designer" performance-boosting steroid tetrahydrogestrinone. Jones had to return the five medals she won at the 2000 Sydney Olympics. In another recent case, sprinter Justin Gatlin, winner of a gold medal in the 2004 Athens Olympics, lost an appeal of a four-year ban for taking steroids. A successful appeal would have allowed him to compete in Beijing.

Jacques Rogge, IOC president, assured reporters at a briefing last month that the committee is making a strong effort to keep the competitions drug-free. "We are at the forefront of the effort to eradicate doping," he said. IOC "owes" it to those who compete without drugs "to ensure the Games are as free of prohibited drugs as possible."

Although Arne Ljungqvist, chairman of the IOC Medical Commission, acknowledged at the briefing that it is tough to catch athletes who cheat, he said scientists' ability to detect doping is improving. "While it is to our advantage to not release all the details, enhanced testing will be administered in Beijing," he said. "You can expect continued efforts to detect human growth hormone (hGH) and erythropoietin (EPO)."

Olympic officials first tested for EPO in 2000 and introduced tests for hGH in 2004. Both are products of recombinant DNA technology. Unscrupulous athletes use hGH, a peptide that stimulates growth, to increase muscle mass and enhance athletic performance. They use erythropoietin, an agent that stimulates red-blood-cell formation, to increase endurance.

The China Anti-Doping Agency will conduct about 4,500 tests at the Beijing Games—up 25% from the number done in Athens four years ago. Additional drug tests conducted by antidoping agencies of competing countries will check all of the athletes who compete in Beijing at least once either before or after the Games.

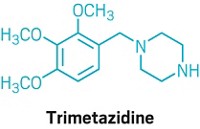

IOC tests for nine classes of prohibited drugs in competitive events: anabolic steroids, hormones, β-2 agonists, hormone antagonists and modulators, diuretics, stimulants, narcotics, cannabinoids, and glucocorticosteroids. Trying to get a handle on what they see as a growing EPO problem, Olympic officials pledged to conduct 800 urine EPO detection tests and 900 EPO blood tests. According to Ljungqvist, "The most comprehensive testing in sports history" involves about 1,000 people, many of them volunteers, including collection personnel, sample chaperones, coordinators, and lab technicians.

New IOC rules this year will raise the ante for athletes who get caught doping. The IOC executive board ruled that any person suspended for six months or more for violating doping regulations will not be able to participate in any capacity in the following summer and winter Olympic Games. That means that those suspended this year won't be able to participate in the 2010 Olympics in Vancouver or the 2012 Games in London. In addition, athletes who skip a drug test on two separate occasions during the Games, or on one occasion during the Games and two others in the 18 months prior, will be considered to have violated antidoping rules.

The Chinese antidoping agency is conducting tests during the Games in a new lab at Beijing's Olympic Sports Center under the authority of IOC and the watchful eye of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), an independent nonprofit organization created in 2000 to govern drug testing and education of elite athletes. Chinese authorities say they spent $10 million on the new 54,000-sq-ft lab including, according to one report, $2.7 million in testing equipment. The antidoping budget for the summer Olympics in Athens was about $6 million, including a new lab building and equipment.

The Chinese lab at the sports center normally has a staff of about 60 from the National Research Institute for Sports Medicine, the State General Administration of Sports, and the Chinese Olympic Committee Anti-Doping Commission. But staff from local hospitals and experts from outside the country will also be there over the next two weeks.

Stuart P. Cram, strategic marketing vice president at laboratory equipment maker Thermo Fisher Scientific, estimates that more than 150 people are running the antidoping lab at the Games. Cram, who helped establish the Beijing lab, as well as those in Athens and at previous Olympics, says setting up an Olympic antidoping lab is a six-year project. "Almost as soon as a country wins the right to host the Games, they begin to plan for a drug-testing lab," he says.

The lab in Beijing has between 60 and 80 instruments of all sorts, according to Cram. Thermo Fisher supplied two DFS Sector Field gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) systems, a Delta V isotope ratio mass spectrometer, and four triple-quadrupole TSQ Quantum Access liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS) systems. The systems are highly automated and computerized to capture test results, he says. And Thermo Fisher will have service engineers on-site day and night to help keep equipment operating without interruption and at peak efficiency.

In most cases, "we supplied more than one instrument in case one fails," says Jeff Zonderman, Thermo Fisher director of clinical and toxicology LC/MS. The triple-quadrupole instruments are useful for an initial scan of samples. The isotope ratio mass spectrometer can, for instance, distinguish between natural and synthetic steroids, Zonderman explains. They are an advance over earlier radioimmunoassay tests, he adds, in part because their specificity means fewer false positives. The DFS Sector Field GC/MS is especially good at high-resolution confirmatory scans for illegal substances.

Most of the samples from athletes are collected and prepared during the day, Cram says. Tests generally run overnight. Every day during the Olympics at about noon, a committee reviews results and judges whether an athlete's sample shows evidence of doping. Positive samples then undergo confirmatory tests.

Agilent Technologies is a major supplier of instrumentation to the China Anti-Doping Agency. The agency is using 18 of the firm's LC/MS units and 19 of its GC/MS units. Agilent's complement of instruments in Beijing will include triple-quadrupole LC/MS, single-quadrupole LC/MS, and ion trap LC/MS, says Stephen B. Crisp, the firm's international business development manager. Other instruments on loan to cope with the Olympic workload will bring the number of Agilent instruments at the lab to 45, Crisp says.

The Beijing lab will use screening methods that vary depending on the drugs athletes tend to favor in a particular competition. "Different compounds are suspected in different sports," Crisp explains. And like Thermo Fisher, Agilent has a number of technicians in Beijing available 24 hours a day, seven days a week to help maintain its equipment. Between the technicians preparing and running samples, the international observers, and the service personnel, the Beijing lab "will be a beehive of activity," he says.

Important to the efficient operation of GC/MS and LC/MS instruments at the Olympics are the solid-phase extraction columns that clean up and concentrate target compounds from urine for analysis, says Terrell Mathews, product manager for Phenomenex, a maker of separation columns. Sample purification steps can take 60% of a lab technician's time and can be a significant source of lab errors, he says.

Antidoping pioneer Catlin says WADA doesn't specify use of any particular manufacturer's equipment; it only sets operating parameters for lab hardware and the consumables they require. Compared with when he started in the field in the early 1980s, the instruments of today are "more sensitive, more capable, more reliable, and last longer," Catlin says. "They also do more heavy-duty work than they did early on."

Still, Catlin says, it is hard to find drug cheats. "Drug users and their assistants are working around the clock to beat analytical scientists," he says. The difficulty is in identifying custom-synthesized "designer" drugs, because analytical instruments aren't set up to detect them. In fact, it took a sample sent to antidoping officials by an anonymous coach for Catlin and his associates at the UCLA lab to identify the tetrahydrogestrinone dispensed to Jones and other athletes by the now-infamous Bay Area Laboratory Co-Operative.

"THE AMOUNT of drug misuse in sports is astonishingly high, and it is escalating," Catlin asserts. Although many in the sports world agree with him, official statistics don't prove widespread doping. According to IOC, officials identified only 26 doping cases—just 0.7% of tests conducted—during the 2004 Athens Olympics. At Sydney in 2000, testing revealed only 11 cases of doping—fewer than 0.5% of tests conducted.

A compilation of laboratory analysis statistics for all 33 WADA-accredited labs, covering a wide variety of sports played worldwide during 2007, reported finding the presence of drugs in just 1.97% of more than 25,000 samples. The year before, WADA labs found drugs in just 1.96% of samples.

In 2007, the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency (USADA), which coordinates testing of U.S. Olympic athletes in training, reported potential doping violations for 48 U.S. athletes, or just 0.6% of samples. The agency sanctioned 15 athletes, including three who did not report for tests. Another 25 cases resulted in a determination of no violation, and eight others are awaiting resolution.

But just because few athletes are caught cheating doesn't necessarily mean that doping is rare. Caroline K. Hatton, former associate director of the Olympic Analytical Laboratory that Catlin founded, says, "It is easier to cheat than to catch cheats." Now a private consultant to antidoping organizations, Hatton points out that "to prove athletes did something prohibited takes a lot of scientific work. Scientific and legal standards are very high. You don't want to wrongly accuse someone. You need to be 100% certain."

Hatton suggests that more money needs to be devoted to catching those who take banned substances. IOC, for instance, generated income of $4.2 billion in the 2001–04 Olympic cycle. WADA's budget this year is $28 million; USADA's is about $13 million.

Those budgets pay not only for drug testing but also for research into new drug-testing protocols. In 2007, WADA said it would provide $6.6 million in funding for 40 research proposals. Among them are projects to study new anabolic steroids, examine human growth hormones and methods to detect them, and identify and detect drugs that boost blood oxygen levels.

Also receiving WADA funding is research into expected new forms of cheating through gene-transfer techniques, which involve injecting genetic material to make an athlete stronger or faster. Among the so-called gene-doping techniques anticipated in the future are the use of plasmid vectors or RNA interference to regulate gene expression.

ONE WADA-FUNDED project, for instance, is looking at the development of a kit that would detect plasmid gene-transfer vector sequences in blood to ferret out genetically modified athletes. Another project is looking at the potential use of short interfering RNA molecules to artificially shut off the body's production of myostatin. Because myostatin is a negative regulator of skeletal muscle growth, the lack of it could enhance human muscular development. Researchers will look to develop urine and blood tests to detect myostatin-targeted molecules.

Advertisement

WADA has even funded preliminary research into setting up a bioinformatics facility where scientists would develop tests that detect changes drugs cause in genes and in the proteins of athletes' tissues. Such an approach could sharpen efforts to definitively identify an athlete's exposure to performance-enhancing drugs.

Other organizations, such as USADA, also invest in research to prevent drug abuse. Last year, the U.S. agency invested more than $1.7 million in projects that included development of biomarkers to test for hGH, improvements in GC and other analysis techniques, and the development of improved tests for blood transfusions between individuals.

Although scientists have made progress over the past 25 years in designing fast and accurate tests, many of them are frustrated by the perceived high level of cheating that still goes on. Preventing it is a cat-and-mouse game. WADA is trying to get out ahead of the next trend in drug use with research into bioinformatics and gene doping. But all too often, scientists are slow in identifying and testing for the latest drugs. "We'll never catch every cheater," Hatton says. "But we'll make athletes think twice before they do cheat."

- » Drugs At The Starting Line

- The Olympics begin with new antidoping lab and measures to keep athletes honest

- » Groups Push Long-Term Efforts To Stop Drug Abuse

- Several groups are trying their hand at setting up long-term monitoring programs to be sure athletes remain drug free

- » Drug Tainted Food Is A Concern For Athletes

- Many athletes preparing for the Olympic Games considered more than their physical training

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter