Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Pharmaceuticals

India Gets In The Race

Indian companies make headway in the risky drug discovery business

by Lisa M. Jarvis

January 28, 2008

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 86, Issue 4

IN A CRISP white shirt and cuff links, Rajinder Kumar doesn't come off as much of an athlete, much less a long-distance runner. But Kumar, president of research, development, and commercialization at Dr. Reddy's Laboratories, is participating in a marathon of sorts—the race to become the first Indian company to bring a new chemical entity (NCE) to market.

As Kumar knows from his days as a clinician at SmithKline Beecham, bringing a novel drug to market requires the skills of a marathoner: endurance, the ability to formulate a careful plan for each leg of the race, and to respond to unexpected challenges along the course, and a lot of faith that the long-term reward is worth the near-term pain.

After years known primarily as generic drug makers, Indian companies such as Dr. Reddy's and Ranbaxy Laboratories are joining the drug discovery and development race. They are banking on their tenacity and ability to quickly adapt to new markets to edge their way in among the more-established pacesetters.

Much has been made of India's meteoric rise as an able assistant to Western drug companies. In just a few short years, Indian contract manufacturers have gone from supplying basic chemical intermediates to becoming trusted partners to big pharma. Meanwhile, a select group of contract research organizations has become the latest extension of big pharma's science team since India's adoption of international patent laws in 2005.

It therefore seems obvious that the next step in the development of India's pharmaceutical industry would be for companies to move from helping others to helping themselves—that is, to discovering, developing, and commercializing their own drugs. And now that Indian companies are in the global spotlight, they are able to attract talent like Kumar, who helped develop and launch the blockbuster anxiety treatment Paxil, to help shape their fledgling drug discovery efforts.

In the past five years, a number of Indian drug firms have started up dedicated R&D operations. The first fruits of their labors—a few NCEs—could reach the market as early as 2010. But even with the first batch of drugs poised to reach patients, executives and industry observers alike acknowledge that establishing a competitive drug industry in India will be a much slower process than its evolution as a contract services partner.

TEN TO 15 years ago, a wave of U.S. biotech companies similarly set up shop as drug discovery service providers, notes Stefan Loren, vice president of the hedge fund Perceptive Life Sciences and a Ph.D. chemist who is a longtime watcher of the pharmaceutical industry. But as time went on—and as competition from India and other developing countries emerged—they decided their long-term future would be better secured if they started developing their own drugs. Loren points to companies such as ArQule, Array Biopharma, and Pharmacopeia that now have drugs against novel targets in their own discovery pipelines.

The Indian pharmaceutical industry has its foundations in the generic drug business, where the companies are more like sprinters than the drug discovery marathoners. In generics, the winner is the one that can design around a patent fastest. Even in the services sector, there's an emphasis on meeting a partner's deadline for improving a manufacturing process or solving a drug delivery problem.

The new Indian drug discoverers will succeed or fail depending on how easily they—and the country's science community in general—can shift their mindsets and skill sets to discovering novel molecules. They will also have to be willing to take the risk and financial burden of bringing them to market. Essentially, the challenge is to train an industry of sprinters in how to run a marathon.

Companies cannot just plow through the drug discovery problem with their traditional toolkits and expect results. There is going to be a learning curve, and it will be long. Loren points out that drug discovery and development are not skills that can be taught at a university; success will require a real cultural change in the industry.

"The issue standing in the way of Indian companies is that drug discovery is not simply chemistry, biology, and computer science," Loren says. "It is in and of itself its own science."

Indeed, there are a number of pieces that companies still need to assemble to be successful. "India certainly has a lot of the raw materials to do drug discovery," says Nailesh Bhatt, managing director of Proximare, a Princeton, New Jersey-based pharmaceutical management consulting firm. However, the industry lacks robust talent in several critical areas, including medicinal chemistry and conducting clinical trials. Further, companies still need to convince local investors that the rewards of drug discovery merit the risks.

DESPITE THE CHALLENGES, the list of companies playing in drug discovery is growing rapidly. Dr. Reddy's and Ranbaxy were the first Indian companies to step up to the drug discovery challenge, initiating formal R&D efforts in 1993 and 1994, respectively.

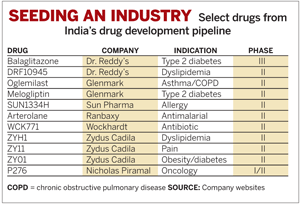

Though it took most companies another decade to get into the R&D game, there are now a substantial number of big-name companies active in drug discovery: Glenmark Pharmaceuticals, Nicholas Piramal India Ltd. (NPIL), Sun Pharma, Lupin Pharmaceuticals, and Wockhardt each have a handful of drugs in their early- and mid-stage pipelines. There is also a healthy cadre of contract research firms getting involved, including Suven Life Sciences, Torrent Pharmaceuticals, and Zydus Cadila.

Many of these companies have long dabbled in drug discovery but began to make a more concerted effort at R&D within the past five years. In most cases, that move to establish a serious drug discovery program has been shepherded by a scientist educated in the U.S. or Europe, or who came from an established career in big pharma.

Despite an early start and the signing of a licensing deal with Novo Nordisk in diabetes, Dr. Reddy's failed for years to gain traction in drug discovery. Eighteen months ago, however, the company recruited Kumar, who had spent his academic and professional career in England, to direct its R&D efforts.

Kumar says he was attracted to the job because Anji Reddy, Dr. Reddy's chairman, and G. V. Prasad, its chief executive officer, convinced him that the company was ready to invest in the people, infrastructure, and skills needed to build a competitive NCE business.

The company now has about 300 scientists in Hyderabad at its R&D facility, which is supported in the U.S. by a research center in Atlanta and a commercial organization in Bridgewater, N.J. In Hyderabad, Dr. Reddy's has been adding critical new technology, such as high-throughput screening, to bring the business in line with competitors in the U.S. and Europe.

Like Dr. Reddy's, NPIL catalyzed its R&D efforts with the addition of a Western-educated and -trained scientist. The firm made its first move into drug discovery in the late 1990s, when it acquired an Indian site that had served as the former German life sciences firm Hoechst's natural products center. The facility had been set up in the 1970s and was not exactly state of the art. But the deal did include a staff of experienced researchers, as well as a natural products collection.

The first three years were marked by a lack of focus. "We were dabbling around with too many targets," says H. Sivaramakrishnan, president and head of chemistry at NPIL's research center in Mumbai. The business didn't truly come together until 2002, when Somesh Sharma joined the company as chief scientific officer. Sharma, who had spent years in the U.S., most recently helping to start a number of California biotech companies, took one look at the old Hoechst labs and saw they needed an overhaul.

NPIL COMMITTED to building a new R&D center in Mumbai. The site, which opened in 2004, expanded the discovery unit beyond lead identification, its strength under Hoechst, into the entire gamut of services needed to bring a drug to the clinic. Those now include basic biology capabilities, medicinal and analytical chemistry services, process research and development groups, and a biomarker program.

Sharma also saw that the fledgling unit needed to focus on a handful of therapeutic areas. The company settled on oncology, metabolic diseases, and inflammation, while also deciding to develop the natural products collection inherited from Hoechst.

Today, NPIL has roughly 320 people working on its NCE platform, another 70 on drug formulation, and about 35 in process development. Of that team, there are about 70 Ph.D.s, most of whom were educated in the West. Sivaramakrishnan notes that it used to be much harder to attract good scientists. "But after we developed this R&D center, a lot of scientists showed interest in coming back from the U.S.," he says.

The kind of whirlwind transition that took place at NPIL is typical of the industry overall; executives readily admit that just a few years ago most Indian drugmakers were known purely for their ability to copy rather than create. Yet even as companies rapidly assemble the technology and skills they need to succeed, they also acknowledge there is still a lot of science to be learned, a knowledge gap reflected in their pipelines.

In many ways, the industry's first drug discovery efforts mirror its history in generics, where Indians specialized in finding quirky ways to manufacture a drug that allowed them to undermine a patent. Many of the molecules coming out of India today are either a more sophisticated take on an older drug or a new attack on a popular drug target.

Most companies' pipelines are rich in prodrugs, which are substances taken by patients in an inactive form that become active when metabolized. And some of the most advanced NCEs are part of drug classes plagued by safety challenges that could block a new entrant from gaining approval.

"They're taking the path of least resistance," Perceptive Life Sciences' Loren says. "Again, this is mirrored by a lot of early, small U.S. pharma companies, where initially they were working on the same targets as everyone else."

Dr. Reddy's most advanced candidate, for example, modulates the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR), the same protein targeted by GlaxoSmithKline's Avandia and Takeda's Actos. In addition to going after a relatively crowded market, the drug, currently in Phase III clinical studies for type 2 diabetes, could face regulatory challenges due to recent concerns over the safety of PPAR modulators.

Indian company executives emphasize that they are more than just copycats. "We are also introducing the element of novel and pioneer targets," Dr. Reddy's Kumar says. Still, he acknowledges that drugs against innovative targets will remain a smaller percentage of the firm's overall pipeline until it has learned all the skills needed to bring them to market.

Two of Glenmark's lead candidates are also entering territory that has proven hard to navigate for larger companies. Melogliptin, a type 2 diabetes treatment, in Phase II trials, acts on dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPPIV), a protease inhibited by Merck & Co.'s Januvia. Novartis has faced lengthy delays for its own DPPIV inhibitor, Galvus, due to concerns that it may be toxic to the liver. Meanwhile, Glenmark's oglemilast, in Phase II studies for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, blocks the PDE-IV receptor, a tricky target that has been the bane of a number of late-stage compounds.

Sun Pharma's lead compound, SUN-1334H, acts on the histamine H1 receptor, a target also blocked by Schering-Plough's Claritin and Pfizer's Zyrtec. Two of Sun's other three pipeline products are prodrugs of currently marketed products, both aimed at improving the absorption of the original compounds.

Companies say there is a clear rationale for going after targets where the biology is well-understood. "We're very early in the drug discovery and delivery system learning cycle," says Uday Baldota, Sun's vice president of investor relations. "Clearly, NCE development is a very high-risk proposition; with our size and scale, we are attempting to pursue projects and products where risk is manageable."

Basically, companies say, the science needs to catch up with the ambition. "We still feel that biology-wise we're not there yet," NPIL's Sivaramakrishnan says, noting that his company is also working primarily on validated targets in its oncology drug discovery program. At the same time, he argues that the company is avoiding crowded targets, while also building up a molecular biology group with expertise in cloning and gene expression that can help move it toward new targets.

Advertisement

Indian companies' caution in their approach to drug discovery stems also from a lack of faith on the part of the financial community. Investors, particularly local ones, have come to expect a healthy rate of return from these companies, and taking on capital-intensive research and clinical trials will surely cut into those profits in the short term.

Companies are trying to placate investors by spinning off their R&D activities. NPIL, Ranbaxy, Sun Pharma, and, most recently, Wockhardt have all announced plans to separate their R&D units from the larger organizations. Dr. Reddy's is the exception. Kumar maintains that the company will not "hive off" its R&D business, but instead it will mitigate the risk by making careful choices about the drugs it pursues.

THIS HIVING strategy is meant to address several challenges to the business, Proximare's Bhatt says. First, there is some pressure from the financial markets to separate the high-risk, high-reward business of drug discovery from relatively low-risk, steady-return businesses in bulk pharmaceuticals and generic drugs.

Hiving also allows the R&D component to be listed on the stock exchange, a move that can potentially create wealth for stakeholders in the original firm, while also generating cash to fund further drug discovery. Ranbaxy, for example, plans to list its business on the Indian stock exchange this year. A company official says the listing "will provide greater flexibility and impetus to our drug discovery research programs, while unlocking significant value for the company and its shareholders."

There is also an issue of attracting and retaining talent, which simply costs more in the NCE business than in generics, Bhatt says. Creating clear lines between the businesses will enable the companies to pay discovery scientists more. "You need a different skill set for NCE development," Dr. Reddy's Kumar says. "On the clinical and regulatory side, there is still a large gap in attracting the right people here."

Lastly, separating drug discovery from traditional generic drug businesses should resolve any worries on the part of potential big pharma partners that would contribute sensitive intellectual property, Bhatt notes.

And partnering has been a critical strategy for companies: The deals help companies learn the ins and outs of drug development from a master, mitigate risk by lifting some of the heavy financial burden of conducting late-stage trials, and alleviate investor concerns by providing a degree of validation of a company's technology prowess. Companies also get critical guidance through the regulatory process, which is much different for NCEs than for generic drugs, Loren notes.

HIGH-PROFILE partnering deals have included Eli Lilly & Co.'s licensing of a Glenmark pain drug in Phase II clinical trials, a major R&D alliance between Ranbaxy and GlaxoSmithKline, and an oncology drug target pact between NPIL and Merck.

"There's been a perceptible change in the views of analysts following our deals with Lilly and Merck," NPIL's Sivaramakrishnan notes.

Eventually, however, Indian companies would like to bring their drugs to market by themselves. NPIL has repeatedly stated that it would like to market its own drug by 2010 or 2011, with the lofty goal of developing that drug for under $100 million.

And though Dr. Reddy's current strategy is to work with partners after the proof-of-concept stage or around Phase II trials, the long-term plan is to commercialize products by itself. Kumar likens the evolution of Indian drug companies to that of those in Japan, which first strengthened their basic research capabilities, then learned the drug development process from their partners.

"There's no reason why Dr. Reddy's couldn't do a Phase III trial itself," Kumar says. "But we wouldn't want to do that until we have the right skills, particularly since a Phase III trial is so resource-consuming."

Such ambitions are admirable, but could be years off closing the science gap, which will require teaching an industry how to discover and develop novel drugs, will not be completed overnight.

But the maturation of one company can really catalyze the industry, Loren notes. In the U.S. industry, for example, early successes at Amgen and Genentech created a team of experienced scientists who eventually moved to other biotech firms, essentially seeding the industry. In India, Loren expects that Dr. Reddy's, which has the most developed program, will likely plant those seeds.

And as Indian companies begin to generate money, they may acquire small U.S. biotech firms that will bolster their pipelines and supply some of the R&D know-how the industry is lacking.

"This is not an overnight process," Loren says. "There are some who simply believe that sheer numbers are going to push this industry forward, but that's not how it works." Instead, there's a natural evolution happening that will, Loren predicts, make India a global contender in drug discovery within the next decade.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter