Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Balancing Energy Needs and Safety

Push to boost natural gas production gives rise to environmental concerns

by Bette Hileman

February 11, 2008

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 86, Issue 6

THE NATION'S EFFORTS to enhance natural gas production and increase energy independence might bring with them new threats. There are growing complaints that gas drilling, particularly in the Rocky Mountain region, is contaminating water supplies with chemicals and endangering human health.

Some environmental and citizens groups claim that exemptions in federal law are responsible for allowing gas operations to contaminate water and air. To remedy this, they are working for changes in federal, state, and municipal regulations. They have succeeded to a degree on the state and local level. And Rep. Henry A. Waxman (D-Calif.), chairman of the House Committee on Oversight & Government Reform, is considering legislation that would end some of the gas industry's exemptions from federal environmental laws.

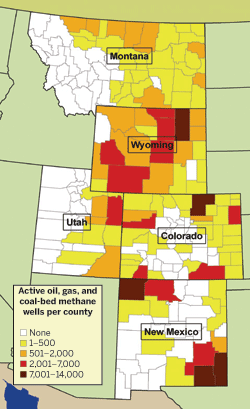

Gas exploration and drilling have increased greatly over the past two decades. According to the Energy Department's Energy Information Administration, between 1990 and 2005, the number of producing gas wells nationwide increased from roughly 270,000 to 425,000. The industry has experienced the greatest growth in Colorado, Montana, New Mexico, and Wyoming.

Waxman and numerous activist groups are especially concerned about the chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing, a method often practiced to enhance production of gas, composed primarily of methane. The procedure begins with the drilling of a production well. Then, a mixture of water, chemical additives ranging from diesel fuel to guar gum, and sand is injected into the well at high pressure. The mixture, or "fracturing fluid," is put in with enough force to form new cracks in underlying rock. Finally, to prepare for actual gas production, engineers pump the groundwater and injected fracturing fluids out from the network of fractures until the pressure declines enough to allow gas to be released from the sandstone or coal.

Three firms—Halliburton, Schlumberger Technology, and BJ Services—have cornered about 95% of the country's hydraulic fracturing business.

According to a highly controversial Environmental Protection Agency report published in 2004, two scenarios can lead to contamination of drinking water from hydraulic fracturing. A hydraulically created fracture may extend into a drinking water aquifer. Or the hydraulically created fracture may extend into a natural fracture that leads to a drinking water aquifer. Some residents who live over or near gas wells have complained that fracturing fluids have ended up in their drinking water, the report says. However, it concludes that no confirmed cases of drinking water contamination have occurred, and that fracturing as practiced in the U.S. "poses only a minimal threat to drinking water supplies."

LATE LAST October, Waxman's committee held a hearing on the loopholes in federal health and environmental protections that are being exploited by the gas industry during exploration and drilling. Witnesses presented highly polarized views of the potential dangers involved.

Amy Mall, senior policy analyst at the Natural Resources Defense Council, testified that gas production is a dirty process. "Many of the steps involved can be sources of dangerous pollution that can have serious impacts on the Rocky Mountain region's air, water, and land—and on people's health," she said.

Despite the toxic materials, such as arsenic, hydrogen sulfide, and benzene, involved in gas production, "the industry enjoys numerous exemptions from federal laws designed to protect both human health and the environment," she said.

One such federal law that creates loopholes for gas exploration and production is the Energy Policy Act of 2005. It exempts hydraulic fracturing from regulation under the Safe Drinking Water Act. Also, it exempts gas production facilities from the Clean Water Act's requirement to control erosion from construction.

In addition to these loopholes, there are loopholes in the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation & Liability Act (Superfund), and the Resource Conservation & Recovery Act, Mall said. The Superfund law has an exemption for natural gas, which contains toxic substances, she explained. Furthermore, exploration and production are not covered by the Toxics Release Inventory set up by the Emergency Planning & Community Right-to-Know Act. This means "companies can withhold information about chemicals, even if it is needed to make informed decisions about protecting health," she said.

"It is time to end the loopholes," Mall urged. "The oil and gas industry should be required to comply with the same statutory provisions as any other industry."

EXACERBATING the issue are those situations in which schools and houses are located very close to gas wells, Mall said. In Garfield County, Colo., 1,179 residential lots and ranches are within 1,650 feet of at least one well. "Many people do not own all of the rights to oil and gas underlying their land and, therefore, cannot stop drilling from happening, even on their own land," she said.

Residents who live near gas wells have experienced symptoms consistent with those known to be caused by the chemicals released from gas drilling operations, Mall said. Some have suffered from nausea, numbness, swelling, skin irritation, breathing difficulties, and headaches, while others have developed thyroid disorders and tumors. "But a direct cause-and-effect relationship between possible toxic exposure and the health problems of these individuals has not been determined," she said. No government or industry group has undertaken the critical health studies that would establish definitive links, she notes.

Each hydraulic fracturing attempt on a gas well uses about 1 million gal of fluid and most wells are "frac'ed" about 10 times, said hearing witness Theo Colborn, president of the Endocrine Disruption Exchange, a nonprofit group that focuses on health problems from low-dose chemical exposures. Many different chemicals—including surfactants, lubricants, foamers, plastics, biocides, antioxidants, acids, and alkalis—are employed for fracturing operations, she said. These chemicals are added to alter the underground strata to allow methane to escape up the well pipe, she said. Her group has identified 171 products used in Colorado containing altogether 245 different chemicals, 92% of which have adverse health effects, she explained.

"Most of the chemicals have multiple health effects," Colborn said. "Some are developmental toxicants as well as endocrine disruptors—that is, they have the potential for adverse health effects on the hormone systems that control the construction of our bodies and how we function."

More than half the volatile chemicals on the list Colborn's group has identified irritate the skin, eyes, nose, lungs, and stomach. Some affect the nervous system, causing headaches, blackouts, and memory loss, she explained. "About 55% can cause cardiovascular and kidney damage, and 35% are carcinogens," she noted.

"We also found that the muds used in drilling are not as safe as industry claims," Colborn continued. Drillers rely on such muds as heavy-duty lubricants. More became known about the muds after blowout during a routine gas drilling operation in Wyoming. The company involved agreed to give local authorities the names of the chemicals in the muds. According to Colborn, they have health effects similar to those of the chemicals employed in hydraulic fracturing.

Drilling muds and hydraulic fracturing are not the only sources of contaminants, Colborn observed. When methane surfaces from a well, it brings with it volatile organic compounds (VOCs)—benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene—that are vented by the tons each year from operational units, she said.

Perhaps one of the most dangerous aspects of hydraulic fracturing is that some of the products used have proprietary ingredients, Colborn said. The material safety data sheets that accompany the products usually include the names of a few ingredients and list others vaguely as proprietary, she said. Only 43% of the data sheets provide the full composition of the product. This can cause problems for residents and workers and emergency crews involved in cleaning up spills.

Despite extensive gas extraction activity under way in Colorado, "there is no database of those exposed as workers or as residents near the extraction or processing sites," said Daniel T. Teitelbaum, an occupational physician and toxicologist from Denver, in his testimony before the House committee. Although there have been documented health complaints by residents of the area and anecdotal stories of medical problems in those exposed, no government agency has asked for an investigation, he said. "The fact that neither government nor industry has undertaken these critical exposure/outcome health studies is inexcusable," he observed. "When the bells are tolled for those injured, who will be willing to take the blame for these failures in preventive medicine?" Teitelbaum asked at the hearing.

Also testifying was Colorado resident Steve Mobaldi. He described the health problems he and his wife, Elizabeth, experienced after drilling operations began near their 10-acre ranch in Rifle. Soon after they moved there in 1995, an oil and gas company started hydraulic fracturing on a property about 300 feet to the west of their ranch.

After a few weeks of drilling, Mobaldi and his wife "began to experience burning eyes and nosebleeds," he said. A few weeks later, Elizabeth began to experience fatigue and headaches, and welts appeared on her skin. "When she showered, she would turn red," Mobaldi said.

Elizabeth's doctor tried several medicines, but nothing helped. Her joints began swelling, and large bumps appeared on her elbows and hands. In 1997, the gas company began drilling a second well that went under the Mobaldi's property. Before the drilling was complete, a well on a neighbor's property exploded, spewing hydraulic fracturing fluid, causing the neighbors to evacuate their house immediately, Molbaldi said.

The next day, the gas company told Mobaldi and his wife not to drink their water, and provided bottled drinking water to them for four months. A few years later, in 2001 and again in 2003, Elizabeth developed pituitary tumors. After trying to sell their house for several years, the Mobaldi family abandoned it in 2004. In 2006, a physician diagnosed Elizabeth with severe chemical sensitivity caused by exposure to toxic substances.

"Later, we learned that many of our former neighbors have similar health problems," Mobaldi said. "If oil and gas companies were required to produce information on the chemicals used, fewer people would suffer."

The government officials who testified at Waxman's hearing, and a gas industry statement submitted to the committee, painted a completely different picture of the safety of gas drilling operations.

Rocky Mountain states now host thousands of oil and natural gas wells

David E. Bolin, deputy director of the Alabama State Oil & Gas Board, said that the two exemptions to environmental laws in the Energy Policy Act have not led to contamination of drinking water supplies. What these exemptions did was remove "unnecessary administrative burdens on the production of oil and natural gas in the U.S.—nothing more," he explained. "Protecting drinking water resources is part and parcel of every state's conservation statute," he said. "The mandate to protect drinking water preceded the passage of the Safe Drinking Water Act."

IN 2002, the Interstate Oil & Gas Compact Commission surveyed hydraulic fracturing in oil and gas producing states, Bolin said. The survey reveals that hydraulic fracturing "is well-understood and well-regulated by the petroleum producing states," he explained. "Furthermore, the report EPA published in 2004 noted that the agency found no confirmed cases of contamination from hydraulic fracturing.

"America needs its production of oil and natural gas," Bolin concluded, "and superfluous regulation only decreases domestic production and increases foreign imports. We in the U.S. have the best-regulated oil and natural gas regime in the world."

Benjamin H. Grumbles, EPA assistant administrator for water, testified that the agency is in the midst of conducting a detailed study of the use of hydraulic fracturing to enhance natural gas production. EPA officials have just completed a tour of seven states, looking specifically at the gas industry. "In the next couple of years, we will be in a position to determine whether to issue a new subcategory of effluent guidelines" for hydraulic fracturing, he said.

"We are committed to using the tools we have under the various authorities—including the Clean Water Act, the Safe Drinking Water Act, and the National Environmental Policy Act—to meet the administrator's challenge to promote the clean development of energy resources," Grumbles said.

The American Petroleum Institute submitted a statement to the committee saying that water typically constitutes about 99% of the liquid phase of fracturing fluids. Also, apparently in an effort to placate concerns, the statement pointed out that the fluids frequently contain a gelling agent, guar gum, which is also used in ice cream, and a buffer, such as fumaric acid, which is found in fruit drinks.

Advertisement

Colorado citizens have received similar reassurances from the Colorado Oil & Gas Association, the industry group for oil and gas in the state, and from federal officials. But last year, the Colorado legislature passed two new laws, House bills 1298 and 1341, designed to put new restrictions on the oil and gas industry.

The laws set up a consultative process for writing new regulations for the industry. They say Colorado must promulgate new rules by July 2008. The process of writing the regulations has to involve consultation with the Colorado departments of wildlife and public health, as well as local communities, farmers, and federal officials.

Both laws involve the Colorado Oil & Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC), which is in charge of approving permits for oil and gas drilling and of inspecting oil and gas operations. In 2006, Colorado had just seven inspectors to monitor more than 20,000 gas wells and more than 10,000 oil wells.

House bill 1298 directs COGCC to "take into consideration cost effectiveness and technical feasibility as it establishes standards for minimizing adverse impacts to wildlife resources affected by oil and gas operations." The rules must encourage operators to utilize comprehensive drilling plans and analyze geographic areas to provide for the orderly development of oil and gas fields. Bill 1341 provides that oil and gas production "must be protective of public health, safety, and welfare."

The new laws were passed primarily because COGCC was overwhelmed with requests for new permits, says Duke Cox, interim director of the Western Colorado Congress, a civic action group. Requests for new gas drilling permits increased from about 1,000 in 2002 to more than 6,300 in 2006, he says, and COGCC did not have the time or the resources to do anything other than give almost automatic approval to most permits.

The Colorado Oil & Gas Association says the proposed regulations, which still are not finalized, will cripple an industry that brings in $23 billion a year and employs 70,000 workers in Colorado.

The New Mexico state legislature is also working on legislation that would mandate stricter regulation of the oil and gas industry.

As federal and state legislators continue to look closely at the practices of drilling companies, it remains to be seen whether federal loopholes that enable gas drillers to skirt federal regulations designed to protect the environment and citizens' health will be closed and how the various state initiatives will play out.

- Balancing Energy Needs and Safety

- Push to boost natural gas production gives rise to environmental concerns

- Diesel Fuel In Hydraulic Fracturing Threatens Aquifers

- The Environmental Protection Agency has been concerned about the use of diesel fuel in hydraulic fracturing operations

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter