Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

German Industry’s Special Edge

Kurzarbeit, a government program to retain employees, eases economic recovery

by Paige Marie Morse

October 4, 2010

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 88, Issue 40

As the world’s economies emerge from the recession, the pace of recovery has been decidedly uneven. In the U.S. and much of the European Union, growth has stalled and unemployment remains near 10%. But Germany stands out, posting growth much ahead of its regional peers and unemployment that hovers at a more comfortable 7%.

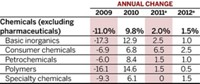

Germany was hard-hit by the global recession: Gross domestic product (GDP) dropped 4.9% in 2009, and chemical output fell 13.9%. But its recovery has been speedy. In the second quarter of 2010, Germany recorded quarter-over-quarter GDP growth of 2.2%, versus 1.0% for the EU overall and just 0.4% for the U.S. Many people in the country believe a big reason for the rapid recovery is Kurzarbeit, a government program that preserves jobs during difficult economic periods.

Most chemical companies operating in Germany held on to workers by taking advantage of Kurzarbeit, which translates as “short work.” The short-work program encourages companies to retain workers during temporary periods of reduced demand by allowing them to reduce workhours; up to two-thirds of the gap in workers’ salaries is then covered by the German Federal Employment Agency. And the companies get a break from social security taxes if they use the time off for employee training.

“Kurzarbeit is a great tool,” boasts Matthias L. Wolfgruber, chief executive officer of the German specialty chemical producer Altana. “It helped us save the jobs and helped us retain the knowledge and know-how of the people.”

This point is echoed at other companies that have operations in the country. “What was most important to us is that we were able to retain our qualified staff,” says Helmut Twilfer, AkzoNobel’s country director for Germany. “Otherwise, we would have had to lay off people.” In contrast, fighting the recession with layoffs was a common approach in the U.S., where more than 10% of chemical company workers were let go in 2009 (C&EN, July 5, page 50).

The German Chemical Industry Association, known by the acronym VCI, reports that at the peak of the downturn in April 2009, nearly 48,000 chemical industry workers were on reduced work schedules. Some 732 member companies of all sizes and end uses participated.

“The German chemical industry had not used this program for 30 years,” says VCI spokesman Sebastian Kautzky, but its impact during the recession is clear. “Our numbers show that German chemical production was down more than 10% for 2009, but employment dropped only 2 to 3%.”

Evidence of the strength of the German chemical industry’s recovery is reflected in recent financial results. Global leader BASF captured a significant improvement in second-quarter performance (C&EN, Aug. 9, page 6), and the firm’s pretax income in Germany for the first half of 2010 was up 120% compared with the same period in 2009.

Altana posted record sales in the first half, Wolfgruber says, and he expects that 2010 will be a record year for his company. “Our recovery has been very strong, and Kurzarbeit is certainly a part of it.”

As recounted by several chemical companies with German operations, the short-work program aided the boost in sales and income earlier this year by enabling a quick response when the business environment improved.

“Kurzarbeit helped the recovery,” asserts Jürgen Lahr, vice president of human resources governance for BASF. “Otherwise, if companies are not sure about whether the crisis is over, they would hire more temporary people before reemploying the people laid off at the beginning of the crisis. This takes much more time.”

The chemical companies that took advantage of the program included major global players such as AkzoNobel, BASF, and Dow Chemical, as well as smaller firms like Altana, Kemira, and Wacker Chemie. Each submitted applications to the German government explaining the need for temporary help during the downturn. Benefits are available to companies for up to 24 months from the start of the reduced work schedule.

Kemira, for example, used short work to cut production at its Leverkusen site on weekends without resorting to layoffs. “When we are ‘driving with full speed,’ we produce chemicals 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” a company spokeswoman says, “but during that year—February 2009 through January 2010—we stopped production on Fridays at 10 PM and continued on Mondays at 6 AM.”

At Altana, use of the short-work program was brief but intense. “In the first quarter of 2009, at its peak, we had more than 20% of our total global employees—more than 1,000 of 5,000 total—using Kurzarbeit,” Wolfgruber says. That translates to four of every 10 of its German employees working on a reduced schedule. But the number of affected employees was down to 400 by July and zero by the end of the year.

“That is the idea of Kurzarbeit,” Wolfgruber points out. “Use it quickly to add flexibility to the workforce and reduce costs at times when you have big swings in demand and manufacturing needs.”

Wacker had a similarly intense period in the first half of 2009. It peaked in April, when 25% of its German workforce was on reduced workhours. “Kurzarbeit proved to be a very valuable instrument,” notes Media Relations Manager Christof Bachmair.

For BASF, implementation varied across its German locations. At one site, a polyurethanes facility in Lemförde, almost all 1,200 employees, including R&D staff, were moved to the short-work program from April through October 2009—with a one-month interruption—reflecting the significant drop in customer demand.

At BASF’s much larger site at Ludwigshafen, only a tiny proportion of its almost 33,000 employees were affected. “Because of the many production plants at that site, applying for Kurzarbeit for the site as a whole was not an option,” BASF’s Lahr says. “We had to go through a detailed process to determine the impact of the decrease in demand on each plant.” The analysis resulted in the decision to reduce operating levels at many units and shut down one of the steam crackers at the site.

The company used some of the reduced operating time for training. It included basic skills such as forklift operation and language classes, but also more focused activities such as the retraining of 20 workers from the shut-down cracker to operate the other steam cracker.

Evonik Industries also used the time off for training, offering more than 100 programs. “About 550 employees working short time at various sites in Germany participated in these training programs,” focused on skills such as laboratory and equipment technologies and production engineering, a company spokesman says. “This improvement of professional qualifications secures the expertise available in the company and, not least, improves employees’ career prospects.”

Not all German chemical companies relied on this program. Bayer and Lanxess both state that they did not take advantage of short-work tools during the recent downturn. Bayer instead reduced workhours by relying on collective agreements with employees that allowed a reduction in workhours with a proportionate reduction in pay. Other companies use that approach as well, when possible.

Using short work to avoid layoffs fits well with German views on labor management, several officials say. “With our social responsibility toward employees,” BASF’s Lahr says, “a layoff is something that we would do anything to avoid. This is quite different if you are a U.S.-based company.”

“Sustaining this social partnership requires that you consider the needs of the employees, not just the shareholders,” Altana’s Wolfgruber says. “That is why we are much more hesitant to let employees go.”

Could a version of Kurzarbeit be applied in the U.S.? Not likely, according to Stephen J. Silvia, a professor in the School of International Service at American University. “Kurzarbeit is a great tool for Germany, but it would not work in the U.S.”

Silvia notes that the program allows the German government to subsidize the high-end export sector, which relies on highly skilled workers. In contrast, the U.S. economy is driven by domestic demand and consumer consumption, fed by less skilled workers. Whereas the U.S. uses stimulus packages targeted at domestic demand, the tools in Germany must be different.

“The strategies pursued by the U.S., namely large tax cuts to individuals and an expansion of infrastructure projects, would never be sufficient to replace demand for Germany’s bread-and-butter export sector,” Silvia says. “It can half-jokingly be said that no domestic economic stimulus could ever be big enough to induce a German family or local government to buy a computer-controlled lathe or 10,000 L of toluene.”

Silvia adds that the cost of Kurzarbeit, which now runs through 2012, is challenging the German government’s goal of achieving a balanced budget.

As is true with all economic stimulus plans, incentives must be scaled back as the market begins to return. But determining the timing is a difficult challenge.

“It is still too early to assess how the intensive use of short-time work will affect the vigor of employment growth in the recovery and economic restructuring in the longer run,” according to an employment report from the Organization for Economic Cooperation & Development. “However, in order to prevent short-time work from becoming an obstacle to the recovery, it is important for crisis measures to be phased out as the recovery gains momentum.”

Most chemical companies report that they have completed their use of Kurzarbeit. As of July, fewer than 5,000 workers were on reduced work schedules, and VCI says the pace of new sign-ups is decreasing. But proponents say the value of the program in aiding Germany’s recovery is clear.

“Chemical companies know that they need skilled people for their complex production process,” VCI’s Kautzky notes. “They kept them during the crisis because they need them for the recovery.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter