Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Recycling Household Gray Water

Water Conservation: Lingering chemicals from personal care products still plague treatment methods for your sink's waste

by Steven C. Powell

August 6, 2010

With many parts of the world suffering from scarce freshwater, recycled household water represents a prodigious potential resource. Some researchers envision neighborhood treatment systems to someday reuse homes' so-called "gray water," the wastewater from sinks and baths. Dutch scientists have now tested these methods and find that despite some success in removing pollutants derived from personal care products, further improvements are needed (Environmental Science & Technology; DOI: 10.1021/es101509e).

Although homes have just one sewer line, conservationists see two distinct kinds of water flowing into it: Toilets generate so-called "black water," whereas sinks, washing machines, and showers produce gray water. Because this gray water constitutes about 75% of household water usage, experts think it's a promising target for local reclamation.

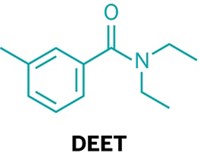

Although gray water has a lighter pollutant load than wastewater from toilets, it still contains chemicals found in personal care products, such as the antibacterial agent triclosan and the preservative propylparaben. Researchers have been developing systems to someday treat gray water within neighborhoods, or perhaps even in individual homes, so it can be reused to flush toilets or irrigate lawns and gardens.

Dutch environmental scientist Lucía Hernández Leal of Wageningen University and the sustainable water research center Wetsus, and colleagues decided to test the treatment methods in Sneek, a town in the northern Netherlands. In a recently rebuilt Sneek neighborhood of 32 houses, environmental engineers designed separate gray water piping systems to pool the waste into a common area for researchers to test new treatment techniques on.

In the laboratory, Hernández Leal and colleagues subjected gray water samples to the typical biological treatments used in sewage facilities: They added sewage sludge to the water, and the sludge's microbes chewed up organic chemical contaminants for 12 hours.

The researchers then analyzed the treated water for 18 compounds from personal care products using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. The sludge treatments removed about 80% of most of the contaminants, but the treated water still contained organic pollutants at low microgram-per-liter levels, which are problematic. For example, at 3.8 µg/L, the sunblock ingredient ethylhexyl methoxycinnamate contributes to the treated water's overall potential as an estrogenic disruptor.

Hernández Leal suggests that further treatment steps, such as using activated carbon or ozonation, might be called for. Eva Eriksson of the Technical University of Denmark thinks the sludge treatments could be optimized. One improvement could be longer treatment times, she says: "With short treatment times of just 12 hours, for example, there's a limit to the kind of substances you can biodegrade."

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter