Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Analytical Chemistry

SpectroPen Pinpoints Lingering Tumor Tissue

Medical Diagnostics: New handheld device could help surgeons excise tumors more effectively

by Rajendrani Mukhopadhyay

October 15, 2010

To combat solid tumors, doctors often rely on surgery along with chemotherapy and radiation treatments. But more than 40% of patients leave the operating room with cancer cells still lingering in their bodies. Now a team of biomedical engineers and surgeons have developed a new spectroscopic pen-shaped device to help surgeons completely excise tumors (Anal. Chem., DOI: 10.1021/ac102058k).

Currently, doctors use techniques such as positron emission tomography to outline a tumor's borders when they plan a surgery, but they can not use these techniques for guidance during the procedure. Magnetic resonance imaging can aid surgeons during an operation, but the process prolongs the surgery's duration and increases costs.

"There currently is no way to find tumors in the operating room except for the surgeons' eyes and hands," says thoracic surgeon Sunil Singhal at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, who helped develop the new device. And tumors can later grow back if surgeons do not completely remove all the cancer cells.

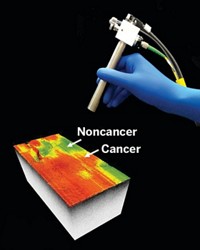

So biomedical engineer Shuming Nie of Emory University and Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta, and colleagues designed a device that a surgeon could use to find these lingering tumor bits and easily wield during an operation.

The probe, called the SpectroPen, consists of two fiber optic cables connected to a spectrometer: One cable transmits near-infrared (NIR) light and the other returns emitted light to the spectrometer. Their technique works with NIR light, because it can penetrate deep into tissue and creates little background noise.

To use the probe, a surgeon first injects the patient with NIR contrast agents, such as indocyanine green, which fluoresces with NIR light, or gold nanoparticles, which produce surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) signals. These chemicals travel through the bloodstream and accumulate around the tumor, because of its leaky blood vessels. When the surgeon points the SpectroPen at a section of tissue, the spectrometer produces either fluorescent or SERS spectra within about a second and can then analyze it for signals from the agent-labeled tumor.

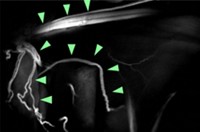

The researchers demonstrated the SpectroPen's capabilities in mice genetically engineered to produce tumors. With the device, they could pick out brightly-colored tumors from the surrounding tissue, because the tumor emitted NIR signals 10-times more intense than those of normal tissue. After surgeons excised the tumor, the surgical cavity becomes dark, indicating that they completely removed the tumor. The investigators have now moved onto clinical trials with the SpectroPen at the University of Pennsylvania.

Pathologist Jeffrey Pinco of Consulting Pathologists of Connecticut, a pathologist group, thinks that the SpectroPen would be most useful in breast cancer surgery, because those tumors have nebulous boundaries. "This device would be one of the greatest leaps in 21st century breast surgery," he says. But, Pinco says, one hurdle for the new probe is whether the SERS contrast agents can garner approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for human use.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter