Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

What A Cell Wants — Chemically Speaking

Microfluidics: A novel microfluidic device probes bacterial movement along chemical gradients

by Jeffrey M. Perkel

November 3, 2010

In classic cartoons, characters drift along wafting scent trails toward freshly baked pies. Similarly, through a process called chemotaxis, bacteria navigate chemical concentration gradients in search of food and friends, and away from poisons and predators.

Chemotaxis represents a classic example of how cells respond to their environments. Researchers have studied it for years, most recently, by watching cells swim through microfluidic devices toward chemicals that attract them. Now Kim Taesung and Kim Minseok of Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology, in South Korea, have upped the ante, developing a chip to probe chemotaxis along six concentration gradients simultaneously (Anal. Chem., DOI: 10.1021/ac102022q).

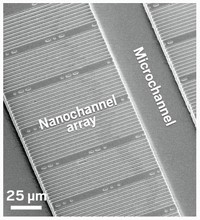

Built of a soft polymer called poly(dimethylsiloxane), Kim and Kim's device resembles a bicycle wheel with six 8-mm-long channels forming the spokes. Reservoirs sit at the center of the wheel and at the end of each spoke. Connecting the radial reservoirs and the spokes are plugs made of agarose gel, which allow potential attractants to diffuse into the channel without "convection" — that is, without generating liquid flows that could push cells around. By loading a chemical into each of the radial reservoirs, and none in the central reservoir, the researchers can produce six stable, linear concentration gradients over a longer distance than any formed in previous device designs, according to the researchers.

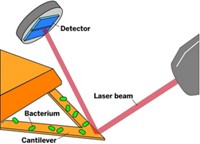

To test the device, the authors created gradients of different sugars and, in another test, of different concentrations of a single sugar. The researchers introduced fluorescently labeled E. coli cells into the central reservoir and allowed the bacteria to follow their noses, so to speak. Half an hour later, the bacteria had migrated to form bands of varying width at different distances down the channels, reflecting each sugar's desirability and its concentration in each reservoir.

Lower glucose concentrations, for instance, produced progressively more-diffuse bands at longer distances from the channel entrance — that is, bacteria swam farther to find the sugar. At the lowest concentrations, no chemotaxis occurred at all. Furthermore, as expected, the bacteria preferred glucose to galactose and mannose, and all three to arabinose and xylose.

"It's a really practical device," says Shuichi Takayama, a professor of biomedical engineering at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, who admires the chip’s ability to test six gradients at once.

According to Kim Taesung, applications include both bacterial and animal-cell chemotaxis.

"I would be interested in using it," says Douglas Weibel, a University of Wisconsin, Madison, researcher who also uses microfluidics devices to study bacterial chemotaxis. He thinks that the new chip could address cellular differences in migrating bacteria populations -- for instance, how cells on the leading edge of migrating bands differ in protein expression from those at the trailing edge.

"When microbiologists start using it, that's when the magic can happen," he says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter