Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Physical Chemistry

Double Duty

Reusing comet-exploring spacecraft yields big payoffs

by Elizabeth K. Wilson

March 7, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 10

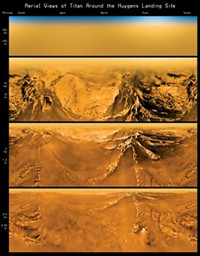

It’s not cheap to explore the cosmos, even though decades of successful robotic spacecraft have certainly delivered scientific pay dirt. These robotic explorers have yielded insights into the physical and chemical workings of our solar system, including Titan’s drenching methane rains, Mars’s complex watery history, Venus’ runaway greenhouse effect, and comets’ inner secrets.

In these tight economic times, it’s not surprising that the National Aeronautics & Space Administration is looking for ways to get more for its money. In the past few years, two NASA spacecraft have made not two—as originally planned—but four visits to three different comets. Thanks to the built-in redundancies and ample supplies on board, these spacecraft have accomplished their primary missions—called Deep Impact and Stardust—as well as a pair of secondary missions—called EPOXI and Stardust-NExT—for not much more than the price of two missions.

“When you have the opportunity to reuse a spacecraft, the additional science you get out of it comes at a really huge discount,” says Tim Larson, project manager for both the EPOXI and Stardust-NExT missions at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory at California Institute of Technology.

The $330 million Deep Impact mission launched the Deep Impact spacecraft in January 2005 to rendezvous with the comet Tempel 1, which it did in July of that year. Deep Impact dropped an 800-lb chunk of metal onto the comet’s surface, and analyzed the material that got kicked up from the resulting crater.

Stardust, built at a cost of $220 million, was launched in 1999. It reached the comet Wild 2 in 2004 and successfully sent a sample of comet dust to Earth in 2006.

Having completed their missions, the spacecraft were still healthy and ready to do more. So in 2007, NASA gave both of them second tasks. Deep Impact headed for a comet named Hartley 2 as part of the new EPOXI mission. The cost for this secondary mission was just $43 million. And Stardust became part of the Stardust-NExT mission, which aimed to take a second look at Tempel 1, costing taxpayers only $29 million.

The new missions yielded plenty of new science. For example, until EPOXI turned its eye on Hartley 2 last year, common wisdom held that a comet’s primary driver was water ice, vaporizing as the comet neared the sun. But Hartley 2’s driving force is the sublimation of carbon dioxide. And Stardust’s examination last month of the five-year-old impact site on Tempel 1 left by Deep Impact shows that much of the dust that was kicked up fell immediately back into the crater. This finding is generating a lot of discussion among team scientists as they mull over its implications for the strength of the material that holds a comet together.

These unexpected findings about Hartley 2 and Tempel 1 have “reinforced the scientific community’s desire to do more comet missions,” Larson says. “It just provides support that these are very worthwhile bodies to visit.” Better characterization of comets’ origins, he says, would tell us much about our solar system.

The secondary missions came about as part strategy, part luck. Not only did the spacecraft have enough fuel on board and redundant sets of electronics, but there were also objects within reach. “It’s certainly serendipitous that we were able to get Stardust-NExT to Tempel 1,” says Lindley Johnson, program director for NASA’s Discovery program, which develops quick, relatively inexpensive space missions.

Mission teams look for other uses for their spacecraft whenever possible, Johnson notes. In fact, the five satellites that made up NASA’s THEMIS mission to study space weather completed the originally defined project in 2010. Now, two of those satellites have been reborn as ARTEMIS, a project to study the moon’s interaction with the sun.

Meanwhile, the comet-exploring spacecraft are nearing the end of their careers. Stardust is “running on fumes,” Johnson says, and will spend its last days imaging Tempel 1 as the comet draws farther away. Stardust will likely be shut down by the end of this month. Deep Impact still has a couple of years’ worth of fuel on board but not enough to reach any more distant objects. So it will take on duties as a planetary observer, Johnson says.

Despite their exciting payoff, secondary missions would be difficult to institute routinely, Johnson says. The potential for Discovery missions to do extended forays does come up during discussions about mission proposals. “We’re not quite sure how formally to do that, but I think it will be a consideration as we do selections for future missions.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter