Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Molecular Megaphone Made-To-Order

ACS Meeting News: Two-component strategy translates trace analytes into a colored readout

by Carmen Drahl

March 31, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 14

A customizable chemical amplifier, created by using a pair of molecules that work together, can detect trace compounds and translate them into a colored signal that is visible to the eye, say chemists at Pennsylvania State University who developed the strategy (J. Am. Chem. Soc., DOI: 10.1021/ja108347d).

So far, the tandem strategy works for low concentrations of palladium, but it could be adaptable for detecting diseases or water contaminants in the developing world. The research was presented on Tuesday in the Division of Organic Chemistry at the ACS national meeting in Anaheim.

Most medical diagnostic kits rely on reagents that require refrigeration or detection schemes that require instrumentation, neither of which are common in resource-poor areas. Chemists have developed stable reagents that don't require refrigeration, but they generally are not easily tailored for detecting different chemical species.

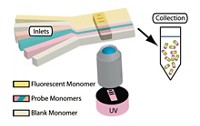

The new approach, by Matthew S. Baker and Scott T. Phillips, combines a detection reagent with an amplification reagent. The detection reagent releases fluoride when it interacts with the substance being analyzed, and the amplification reagent breaks down in response to the fluoride to release amplified quantities of yellow products. The system was sensitive enough to detect 0.36 ppm palladium in water, about the quantity found in roadside soil, Phillips said.

It might be difficult to see the color yellow in real-world samples in which water might be dirty, noted organic chemist Anna Cattani-Scholz of Technical University Munich, who attended Phillips's talk. But it should be possible to modify the reagents to change the visual output, she said.

The method's flexibility makes it promising, agreed organic chemist Vyacheslav V. Samoshin of the University of the Pacific, who presided over the session. A drawback is that it currently takes more than a day to detect trace quantities, he added.

"We're only releasing two fluorides" with the current detection reagent. Phillips said. A molecule designed to release more fluorides at once would make the amplification faster, and his team has such molecules in the works, he added.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter