Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Energy

Nuclear Studies

Japanese nuclear power plant crisis sparks examination of U.S. reactors

by Jeff Johnson

April 4, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 14

The Japanese nuclear power plant disaster is raising new worries and elevating past ones concerning the operation, safety, and age of the U.S.’s 104 nuclear reactors. The surprising power of the earthquake and tsunami, the Japanese utility’s lack of emergency preparation, and the resulting radioactivity leaks and likelihood of a reactor core meltdown have triggered calls by politicians and scientists for an immediate review of all U.S. nuclear reactors.

Calls are particularly zeroing in on reactors similar in location and design to those in Japan.

Sens. Barbara Boxer and Dianne Feinstein (both D-Calif.) are asking the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC)—the federal body responsible for overseeing the nation’s nuclear power plants—to quickly examine the safety and emergency preparedness of California’s San Onofre and Diablo Canyon nuclear generating stations on the shores of the Pacific Ocean near earthquake faults. At the same time, a host of energy groups have requested that NRC halt relicensing of older nuclear power plants, particularly the U.S.’s 23 General Electric Mark 1 reactors whose design is identical to the damaged Japanese ones.

A week after the March 11 earthquake and after a daylong congressional grilling, NRC Chairman Gregory B. Jaczko announced the formation of an internal task force to begin a “systematic and methodical review” of changes that should be made to U.S. nuclear programs and regulations. NRC said the task force will begin its long-term evaluation within three months and complete a full report six months later. Meanwhile, it will provide short-term analyses in 30-, 60-, and 90-day windows while completing the full review.

However, NRC says it will continue business as usual and in fact formally issued a 20-year operating extension for the 40-year-old, 600-MW Vermont Yankee power plant, in Vernon, Vt., just a week and a half after the Japanese disaster. Vermont Yankee is a GE Mark 1 plant and has faced past operational problems, including radioactive tritium leaks. NRC approval came despite opposition from the Vermont Senate and U.S. Sen. Bernard Sanders (I-Vt.).

The U.S. depends heavily on nuclear power plants such as Vermont Yankee, and for decades the industry has hoped for a burst of new nuclear power plant construction. Meanwhile, the U.S. nuclear reactor fleet is getting old—most plants are approaching 40 years in age, seven are 40-plus, and all but three have been running for at least 20 years.

Over the past few years, NRC has issued 20-year extensions for 63 U.S. reactors, because their original 40-year licenses have expired or will soon expire. NRC has never denied an extension request.

These reactors are important to the U.S. economy. Nuclear reactors supply 20% of the nation’s electricity, and for power plant operators, they are one of the best sources. Nuclear power plants can run 24/7, and their greenhouse gas emissions are small—that is, if emissions from uranium mining and enrichment, fuel production, and spent-fuel handling are not figured in.

The situation in Japan, however, shows how such dependence on nuclear power can quickly spin out of control.

On March 11, six reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station were hit hard by the earthquake and tsunami. Three were operating and three were shut down at the time of the natural disasters. When the huge earthquake occurred, the operating reactors automatically shut down. They lost grid power and turned to backup emergency power systems to circulate water to maintain reactor core temperatures.

But with the tsunami, diesel backup engines were knocked out, according to NRC and the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), a science-based nonprofit group. The power plant operators then began injecting seawater and boric acid into the reactor core containment vessels as best they could in an attempt to lower temperatures and avoid a core meltdown.

Despite heroic efforts, the temperature and pressure inside the three reactor cores began increasing. In an attempt to regain control, relief values opened and hydrogen, steam, and radioactivity were released outside the primary containment core. Hydrogen exploded outside the reactors but inside thin-skinned, warehouselike secondary containment buildings, which are part of the GE Mark 1 design. Roofs were destroyed, and radioactivity was emitted into the environment.

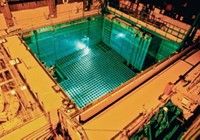

In addition, UCS points to another key source of radioactivity and hydrogen—the station’s seven spent-fuel storage pools, which are particularly problematic for the GE Mark 1 design. Under this design, spent fuel is stored in elevated pools adjacent to the reactors’ primary containment structure. What integrity remains for these pools in the Fukushima Daiichi reactors is unknown. Reports conflict, but it appears the pools likely are losing water and run the risk of catching fire and releasing hydrogen and large amounts of radiation.

The GE Mark 1 design goes back to the 1960s and has been challenged by U.S. regulators beginning in 1971, according to internal documents from NRC and the Atomic Energy Commission, which predated NRC. The material was supplied to C&EN by Beyond Nuclear, a nuclear watchdog group.

Regulators’ concerns centered on primary containment and the possible release and explosion of hydrogen. In the 1980s and ’90s, NRC required modifications to control the buildup of hydrogen in the GE Mark 1 primary containment structures, NRC spokesman Scott Burnell notes. These included new “hardened vents” to control containment pressure by allowing controlled hydrogen releases to the atmosphere outside the primary and secondary containment structures.

It is unknown if the Japanese reactors had been similarly modified. It is also unclear if the released hydrogen and radioactivity came from the primary containment structure or the spent-fuel pools; both have that potential, and both are likely to be damaged.

Use of hardened vents raises concerns for Beyond Nuclear Director Paul Gunter, who sees them as an inadequate, last-ditch effort to avoid core meltdown in the poorly designed GE Mark 1 reactors. He also questions the relicensing process, pointing to a 2007 NRC Office of the Inspector General report that said NRC relicensing auditors rely too heavily on utility material, even copying company information directly into NRC reports.

“It is lamentable that NRC extended the license of the Vermont Yankee reactor, with the same design as the stricken Fukushima units, while the Japanese crisis is ongoing and there has been no time to learn its lessons,” says Arjun Makhijani, a nuclear physicist and president of the Institute for Energy & Environmental Research, a Maryland-based science and environmental organization.

Further, Makhijani says, Vermont Yankee has more spent fuel in its holding pool than the stricken pools at the Fukushima Daiichi plant combined. “I am shocked NRC did not even order the emptying of all of Vermont Yankee’s older spent fuel into dry-cask storage as a condition of the license extension,” he says.

About 22% of U.S. spent fuel is stored in the leakproof, aboveground dry casks that Makhijani refers to, according to the Congressional Research Service. The steel and cement canisters weigh about 120 metric tons each and store about 10 metric tons of spent fuel. In all, at least 63,000 metric tons of spent fuel is stored at commercial nuclear power plants as of late 2009, according to CRS.

However, Burnell says there is no safety-based reason to move spent fuel to dry casks because pool storage is safe. But he expects an examination of spent-fuel storage will be part of the NRC task force review.

He adds that NRC is comfortable with the safety of GE Mark 1 reactors, as well as its process to relicense them. NRC’s relicensing examination, he explains, considers the potential environmental impact of 20 more years of operation and aging. It does not impose new requirements but “gives a plant the opportunity to continue meeting NRC requirements,” he explains.

The number of years of operation is a concern, but age alone may not be an issue, say UCS and the Nuclear Energy Institute (NEI), a trade association.

“There is nothing magic about the original 40-year lifetime of the plants,” says David Lochbaum, director the UCS Nuclear Safety Project, a nuclear engineer, and a former NRC safety trainer who worked at U.S. nuclear plants for 17 years.

“As long as NRC is doing aging management and monitoring the degradation of equipment and replacing or repairing it before safety margins are compromised, then there’s no big problem operating a 45-year-old plant, any more than a five-year-old plant,” Lochbaum explains.

“Accidents at newer plants, like Davis-Besse and Three Mile Island, showed us you can definitely incur problems before 40 years,” Lochbaum points out. “It really depends on how well the plant owner is maintaining the plant and safety margins. We don’t have a beef with that.

“Our concern is that the license renewal process doesn’t look at the aging of the regulations themselves,” Lochbaum says. “Many of the plants have been grandfathered in over the years and have avoided new regulations that were adopted to improve safety in the future.”

The problem, he continues, is that “NRC doesn’t look at the exemptions and the waivers that have been given to plants to see that the basis for the original exemption is still good for 20 more years. We think NRC should be doing that, should have been doing that all along.”

But NRC’s regulations and the industry’s oversight programs for aging reactors are protective, says NEI’s Alex Marion, vice president of nuclear operations. He notes the industry is beginning its own examination of lessons learned from the Fukushima Daiichi tragedy.

That said, he adds, “I personally believe these power plants can run for 80 years.” And indeed, NRC, the industry, and the Department of Energy are examining the technical issues in extending operating licenses a second time.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter