Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Synthesis

Polymer Synthesis On Command

ACS Meeting News: Applied voltage modulates polymerization with precise control

by Lauren K. Wolf

March 31, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 14

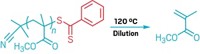

Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) have brought a new level of control to atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP), a reaction that is used to make specialty polymers for products such as adhesives and coatings. By applying specific voltages to an electrochemical cell filled with a solution of catalyst, monomer, and alkyl halide, the scientists are able to turn the polymer formation process on and off at will.

The work, described this week at the ACS national meeting in Anaheim, Calif., and published in Science (DOI: 10.1126/science.1202357), relies on a type of reaction in which a transition-metal catalyst is used to form carbon-carbon bonds.

The addition of electrochemistry to ATRP "enables further polymerization control" than was previously possible, CMU chemist Krzysztof Matyjaszewski said at the meeting. His group developed the new approach, which could lead to the more precise synthesis of polymers of greater complexity.

The inherent rate of ATRP is controlled by a redox equilibrium between Cu(I) and Cu(II) catalyst species in solution. Electrochemistry is ideal for manipulating the reaction in real time because it "can be used to rapidly regulate the concentrations of both of these species," Matyjaszewski said.

In their study, Matyjaszewski and coworkers show that an applied voltage drives the ATRP process toward production of the Cu(I) activator species, which catalyzes the addition of monomer to already-growing polymer chains. A different applied voltage, on the other hand, creates more of the Cu(II) deactivator species and halts the reaction.

In the past, chemists have added reducing agents such as ascorbic acid to ATRP reaction mixtures to efficiently produce polymer by converting Cu(II) to Cu(I). In electrochemically mediated ATRP, "chemical reducing agents are eliminated, and their role is essentially played by an electrode," Matyjaszewski said. This elimination and the reduction in the amount of required catalyst make the reaction more environmentally friendly, he said.

This "landmark" work, said Craig J. Hawker, a polymer chemist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, "affords a fascinating new platform for material design while also solving immediate challenges such as reduction in catalyst loading."

Matyjaszewski said that extension of the technique to ATRP on an industrial scale is feasible, and his group is now optimizing reaction conditions in an effort to achieve that goal.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter