Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Safety

Congress Mulls Facility Security

Committee turf wars complicate effort to renew chemical antiterrorism program

by Glenn Hess

April 25, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 17

Chemical industry officials are working to rally congressional support for antiterrorism legislation that would extend for several years the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) authority to regulate security at thousands of chemical facilities across the nation, without imposing additional mandates and costs on U.S. manufacturers.

But before a bill is sent to the White House for the President’s signature, supporters will have to coalesce around a single legislative vehicle and find a path forward through the political thickets on Capitol Hill.

Turf battles between committees have continually hindered efforts to pass homeland security legislation since the terrorist attacks in September 2001. Although Congress created homeland security committees in each chamber, it did not give them consolidated jurisdiction over homeland security issues, as recommended in 2004 by the bipartisan 9-11 Commission.

In both the House of Representatives and the Senate, multiple panels have overlapping jurisdiction over the Chemical Facility Anti-Terrorism Standards (CFATS), a temporary program created by DHS in 2007.

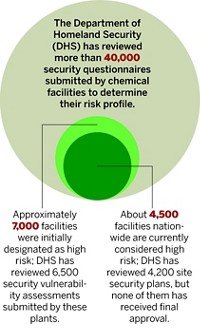

Under CFATS, the department requires high-risk chemical plants and other facilities that use or store threshold amounts of certain hazardous chemicals to complete vulnerability assessments, develop site security plans, and implement protective measures. DHS then conducts audits and inspections to ensure compliance.

Congress directed the department to establish a chemical plant security program in October 2006 under an amendment added to the Homeland Security appropriations bill for fiscal 2007. However, the legislation gave DHS only three years to get the program up and running.

Congress was expected to give DHS permanent authority to regulate security at chemical facilities before the temporary program expired in late 2009. But lawmakers have been unable to agree on how to structure the program long-term, and CFATS has been kept alive through the annual appropriations process.

This situation has led to the introduction of several bills in the House and Senate that would continue the security plan largely as it now exists. The Obama Administration’s budget proposal for fiscal 2012 requests that the authorization for the CFATS program be extended to Oct. 4, 2013, effectively a two-year extension. CFATS is currently authorized until Oct. 4, 2011.

“CFATS is by far the most robust, comprehensive, and demanding chemical security regulatory program to date,” says Timothy J. Scott, the chief security officer and corporate director of emergency services and security at Dow Chemical, the nation’s largest chemical maker.

The regulatory program offers flexibility and minimizes its economic impact “by not dictating the implementation of specific measures, which allows facilities to take into account other important considerations, such as labor costs, managing energy consumption, and ensuring worker safety when securing their facility,” Scott remarks.

The chemical industry has invested more than $8 billion to enhance both physical and cybersecurity protections at its facilities since 2001, according to the American Chemistry Council, a trade group representing more than 140 major chemical manufacturers, including Dow.

Earlier this month, the House Homeland Security Subcommittee on Cybersecurity, Infrastructure Protection & Security Technologies advanced a bill (H.R. 901) that would extend DHS’s current regulatory authority over chemical facilities through 2018, giving the department seven more years to fully implement the CFATS program.

“Although implementation has been slower than Congress wanted, CFATS is working,” Rep. Daniel E. Lungren (R-Calif.), the bill’s chief sponsor, remarked on April 14 shortly before the subcommittee voted to send the measure to the full Homeland Security Committee. “It is building a foundation of security in the chemical industry which will protect our citizens and our economy from future terror attacks,” he remarked.

Significantly, the bill would codify the authority for the program within the Homeland Security Act—the law Congress passed in 2002 that created DHS. This would likely give the Homeland Security Committee primary oversight and funding responsibility for CFATS and jurisdictional advantage over the House Energy & Commerce Committee. The two panels now jointly oversee the program.

Reps. Tim Murphy (R-Pa.) and Gene Green (D-Texas), both members of the Energy & Commerce Committee, have proposed similar legislation (H.R. 908) that would simply extend the existing CFATS program for six years through 2017.

Which bill will advance to the House floor is ultimately up to party leaders, Lungren notes. But Murphy says the two bills will likely be reconciled. “We’ll work something out in the long run,” he says.

Democrats on the Energy & Commerce Committee have expressed strong support in the past for expanding the CFATS regulatory regime to also cover security at drinking water treatment plants, which use large amounts of chlorine and other toxic chemicals. The Murphy-Green bill would allow the Energy & Commerce Committee to maintain a role in congressional oversight of CFATS and could set the stage for amendments later in the legislative process that would alter security requirements at drinking water facilities.

Democrats have also expressed an interest in extending the CFATS regulations to wastewater treatment plants. That could add another procedural hurdle because the House Transportation & Infrastructure Committee has jurisdiction over those facilities.

Meanwhile, Sen. Susan M. Collins of Maine, ranking Republican on the Senate Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs Committee, has reintroduced a bipartisan bill (S. 473) that the panel unanimously approved last year. The measure would extend the current CFATS program by three years and direct DHS to provide more compliance assistance to the chemical industry. Sens. Mary L. Landrieu (D-La.), Rob Portman (R-Ohio), and Mark L. Pryor (D-Ark.) have signed on as cosponsors.

“Simply put, the program works and should be extended,” Collins says. “Chemical facilities are tempting targets for terrorists. DHS has done a good job developing a comprehensive chemical security program.”

Landrieu says the legislation will improve CFATS by promoting collaboration with state and local authorities and providing facility operators with technical assistance, information about best practices, and enhanced opportunities for safety training and exercises. “Extending the program with those added improvements makes sense,” she remarks.

None of the legislative proposals would impose any additional requirements on chemical facilities, such as a mandate for so-called inherently safer technology (IST). A chemical security bill passed by the House in November 2009 (H.R. 2868) would have required high-risk facilities to consider whether they could reduce the consequences of a terrorist attack by using a less toxic chemical or a safer process.

In addition, facilities that DHS deems to pose the highest risk would have been required to adopt safer technology, provided implementation was feasible and would not merely shift the risk to another location.

The bill failed to become law in the last Congress, but the mandatory IST concept has been revived in legislation (S. 709) introduced by Sen. Frank R. Lautenberg (D-N.J.).The legislation would also eliminate the current law’s exemption of 500 port facilities, including the majority of U.S. refineries. A separate proposal (S. 711) would give the Environmental Protection Agency authority under CFATS to regulate security at drinking water and wastewater facilities.

Lautenberg sits on the Senate Environment & Public Works Committee, which would have to approve expanding CFATS to cover the nation’s 2,400 water treatment plants because the panel oversees EPA’s regulatory activities under the Safe Drinking Water Act.

“A catastrophic accident or terrorist attack at one of America’s chemical plants or water treatment facilities would have devastating consequences for the surrounding communities,” Lautenberg says. “When companies use dangerous chemicals, it is essential that they also use the safest methods available. This commonsense legislation would ensure a thorough review of risk and help us move toward more secure plants and safer communities.”

Chemical industry officials are urging Congress to approve a long-term extension of CFATS, but they adamantly oppose an IST mandate.

“We’re encouraged by Congress’ swift attention to chemical security so early in the 112th Congress,” says William E. Allmond IV, vice president of government relations at the Society of Chemical Manufacturers & Affiliates (SOCMA), a trade group representing the batch, custom, and specialty chemical industry.

“SOCMA strongly supports extending the current standards without any significant programmatic changes to allow chemical facilities to fully comply,” Allmond says.

But the need for annual reauthorization of the program has created uncertainty for facilities regulated by CFATS, he notes. “Without the assurance of a long-term authorization of these regulations, companies run a risk of investing in costly activities today that might not satisfy regulatory standards tomorrow,” Allmond asserts.

Andrew K. Skipp, chairman of the National Association of Chemical Distributors (NACD) and president and chief executive officer of chemical distributor Hubbard-Hall, says CFATS has been and will continue to be a major regulatory commitment for the industry.

“While we have been willing to invest the time and resources to comply with this important regulation, I know that Hubbard-Hall along with all of the other members of NACD who have CFATS-covered facilities would appreciate the certainty of a clean, long-term extension of the program,” Skipp says.

Lautenberg’s bill (S. 709) is strongly backed by environmental activists and labor groups, who argue that an IST mandate—along with bringing water treatment and port facilities under the CFATS umbrella—would close dangerous gaps in security.

The two House bills and Sen. Collins’ legislation “are an irresponsible distraction from a long overdue comprehensive security program,” says Rick Hind, legislative director for Greenpeace, an environmental organization. All three proposals “fail to require any disaster prevention at the highest risk chemical plants.”

Safer processes may not be feasible in some circumstances, but they should at least be considered in a security plan, says James S. Frederick, assistant director of health, safety, and environment at United Steelworkers (USW).

“Many safety measures may be possible without expensive redesign or new equipment. Safer fuels or process solvents can be substituted for more dangerous ones. The storage of highly hazardous chemicals can be reduced,” Frederick says.

Merely extending the current CFATS regulations would jeopardize the hundreds of thousands of USW members employed at chemical-related facilities and residents who live in surrounding communities, adds USW International President Leo W. Gerard. “We support the more comprehensive bills introduced by Sen. Lautenberg to address the preventable hazards these plants pose,” he remarks.

The Obama Administration also supports expanding the CFATS program to include a requirement for safer technology. Rand Beers, under secretary of the National Protection & Programs Directorate at DHS, told the House Energy & Commerce Subcommittee on Environment & the Economy last month that all high-risk chemical facilities should conduct IST assessments.

In addition, Beers said, the federal government should have the authority to require plants posing the highest risk to adopt safer technology if the measures enhance overall security and are determined to be feasible.

SOCMA’s Allmond, however, says that IST is a process-related engineering concept, and there is no agreed-upon methodology to measure whether one process is inherently safer than another. “The world’s foremost experts in IST and chemical engineering have consistently recommended against regulating inherent safety for security purposes,” he remarks.

M. Sam Mannan, a Texas A&M University chemical engineering professor, testified in February that U.S. facilities could be “put at a competitive disadvantage if required to implement unproven technologies simply to meet a regulator’s position that such technology is more inherently safe.”

He told the House Homeland Security Committee that in some cases, a seemingly clear choice with regard to inherent safety may create some undesired and unintended consequences, such as reducing risk associated with transport of a chemical while increasing the risk of storing that chemical.

For most chemical distribution facilities, Hubbard-Hall’s Skipp contends, an IST assessment would likely produce limited options that would impede normal business operations.

“Particularly in these tough economic times, and in addition to the myriad regulations that already affect us, [an IST requirement] could be the final straw to put some companies out of business, which would result in further job losses,” he says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter