Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Policy

EPA-Favored Cleaning Products

Disclosure is now part of requirements for use of agency’s logo on product labels

by Cheryl Hogue

May 9, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 19

When it revised the standard for its Design for the Environment (DfE) logo on cleaning products last month, the Environmental Protection Agency says it sought to balance consumers’ demand for information with producers’ need to protect proprietary formulas.

Despite the agency’s effort, not all stakeholders are satisfied. Some product formulators are generally pleased with the agency’s revised standard. Environmental groups are, too. But one key industry association, the American Cleaning Institute (ACI), says the disclosure requirements in the updated standard could backfire, deterring companies from participating.

Begun in 1997, DfE is a voluntary program that encourages development of safe, green products, including cleaning products. It allows companies to use the program’s EPA-sanctioned logo on product labels. The agency limits use of the emblem to goods that are free of chemicals of potential concern, such as carcinogens or reproductive or developmental toxics. To carry the logo, a product must contain only ingredients that EPA has screened and found to be safer than most chemicals in a particular category, such as surfactants and solvents.

The updated DfE criteria for cleaning products go beyond the voluntary ingredient disclosure initiative launched in 2010 by ACI, the Consumer Specialty Products Association, and the Canadian Consumer Specialty Products Association. But EPA’s new standard is less stringent than steps announced in April by Whole Foods Market, a grocery chain that sells “natural” and organic goods. The retailer will require by 2012 that all household cleaning products it carries list every ingredient on their labels.

Under its revision, EPA requires companies to make public all ingredients—except those claimed as trade secrets—in products that carry the DfE logo. The agency encourages formulators to list ingredients on the product label, but they can also refer consumers to a website or toll-free number to get this information. In addition to providing the name of each substance, companies must list each compound’s Chemical Abstracts Service Registry Number.

ACI, previously known as the Soap & Detergent Association, is disappointed with the updated standard. The industry group, which supports DfE, says the new requirements could discourage companies from participating in the program and could pose barriers to innovation. Kathleen Stanton, director of technical and regulatory affairs at ACI, says the updated standard could set a precedent for states or other jurisdictions that may decide to establish mandatory programs for communicating ingredients in cleaning products.

EPA’s requirement for disclosure of CAS Registry Numbers of ingredients also worries ACI. Stanton says the numbers can make ingredient lists appear too technical and less friendly to consumers.

The numbers “are really helpful for researchers and advocates,” but not for the average consumer, says Jamie Silberberger, director of programs and policy for Women’s Voices for the Earth. This environmental group has for years sought disclosure of all ingredients in cleaning products and cosmetics, including fragrance components.

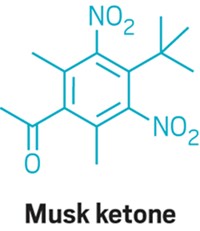

The identity of fragrance compounds is perhaps the most controversial issue that EPA addressed in revising the DfE standard. The updated requirements allow companies, as part of their ingredient disclosure, to direct consumers to a list of chemicals on the International Fragrance Association’s website.

But the fragrance association’s list contains thousands of compounds, Silberberger points out. This isn’t helpful to consumers who want to avoid specific chemicals, she says.

In its revised standard, EPA points out that formulators often don’t have, or by contract cannot divulge, information on fragrance ingredients. Gretchen Schaefer, a vice president for the Consumer Specialty Products Association, calls fragrance formulas “uniquely proprietary.”

In a less-is-more twist, the revised DfE standard allows participating companies to list particular chemicals, including fragrance compounds, that a product does not contain. Declaring that a product is free of certain substances that are suspected of triggering asthma or allergies “may provide important public health information,” according to an EPA document accompanying the DfE standard for cleaning products.

The demand for ingredient information goes beyond the household market, says Bill Balek, director of environmental services and legislative affairs for ISSA. This trade group represents sellers and purchasers of cleaning products for commercial use.

Balek says institutional purchasers of cleaning products are increasingly demanding ingredient disclosure, as well as information on a product’s environmental performance, such as biodegradability, and efficacy as a cleaner.

“The consumers are really driving the market,” Balek says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter