Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Policy

Countdown To Budget Control

The fate of future science funding hangs in the balance as supercommittee works to finalize deficit control plan

by Susan R. Morrissey

November 21, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 47

This week the first step will be taken toward controlling the federal deficit, something that has garnered widespread attention, including that of the science community. By Wednesday, Nov. 23, the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction—the so-called supercommittee—is to have completed its work on a plan to trim at least $1.2 trillion over the next decade from the federal budget.

Once the supercommittee releases its plan, Congress will have until Dec. 23 to vote on the measure, and if it is approved, President Barack Obama will have until Jan. 15 to sign it into law. If a deficit-cutting measure fails to become law by the middle of January, automatic, across-the-government spending cuts will kick in with fiscal 2013 to achieve the statutory reductions. These cuts will affect both nondiscretionary funding—spending enacted by law, including entitlement programs—and discretionary funding—the money that supports federal agencies.

This process was set in motion in August when Congress passed the Budget Control Act of 2011 (C&EN, Aug. 8, page 12). That law immediately cut about $900 million in discretionary funds and set caps on discretionary funding through 2021. It also established the supercommittee and tasked it with coming up with at least $1.2 trillion in deficit reductions across the entire federal budget by 2021.

“This committee has been working hard over the last few weeks to come together around a balanced and bipartisan plan to reduce the deficit and rein in the debt,” Sen. Patty Murray (D-Wash.), cochair of the supercommittee, said prior to the panel’s third hearing, which was held on Oct. 26. To date, the supercommittee has held four hearings to gather input for the reduction plan.

Congressional committees, organizations, and individuals are also supplying the panel with advice about which programs to cut and which ones to protect. According to Murray, input has come in from close to 185,000 sources.

Several scientific organizations have sent letters to the supercommittee in support of continued federal support for R&D. The groups underscore the importance of sustained scientific funding and the importance of R&D to economic prosperity.

For example, a letter from a coalition of nearly 70 universities and professional scientific societies led by the American Association for the Advancement of Science urged the panel to protect scientific funding.

“We urge you to keep in mind that drastic cuts to research investments in the discretionary accounts, both defense and nondefense, would set a dangerous precedent that would inhibit immediate scientific progress and threaten our international competitiveness long into the future,” wrote the group, which includes C&EN’s publisher, the American Chemical Society. The letter added that a bipartisan debt commission last year identified federal R&D as an area of investment too critical to be cut.

Graduate students are also banding together to voice support for science to the supercommittee. Stand with Science—started by the Science Policy Initiative, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology graduate student science and engineering group—produced a video laying out the importance of federal funding to research and asking graduate students to sign a letter to the panel.

If the supercommittee fails to come up with a plan, Congress fails to pass the plan, or the President doesn’t sign the plan into law by the statutory dates, automatic cuts go into effect beginning in January 2013.

Such cuts would be “like taking a sledgehammer to an operation that requires a scalpel,” says Anthony Pitagno, assistant director for advocacy at ACS. “The problem with this is that you’re not distinguishing between what is a growth area for federal investment and what’s not.” Instead, all agencies would most likely see significant budget cuts over the next decade, he notes.

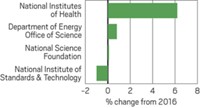

The immediate impact on science agencies was outlined by Rep. Norman D. Dicks (D-Wash.) in an October letter to the supercommittee. Dicks is the highest-ranking Democrat on the House of Representatives Appropriations Committee. He wrote that, among other impacts, the automatic cuts would mean 2,500 to 2,700 fewer research grants by the National Institutes of Health in 2013 and a reduction of about $530 million in the National Science Foundation’s 2013 research grant and education programs.

For its part, the Administration fully expects the supercommittee to come up with a deficit reduction plan and Congress to approve it, according to a spokesman. Therefore, he continues, agencies are not currently preparing contingency plans to deal with across-the-board cuts.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter