Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Oil Dispersants Persist in the Deep

Gulf Spill: Researchers find that an anionic surfactant lingers months after its use in response to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill

by Laura Cassiday

February 2, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 6

As crews worked feverishly to plug the Deepwater Horizon wellhead in the Gulf of Mexico last spring, BP officials decided to inject 2.9 million L of a chemical dispersant into the stream of oil gushing from the ocean floor. This spill marked the first time that crews had applied dispersant deep underwater, so nobody knew the chemicals' fates or their environmental consequences. Now researchers have tracked a key ingredient in the dispersant and found that it was unexpectedly persistent in deep ocean waters (Environ. Sci. Technol., DOI: 10.1021/es103838p).

Dispersants contain surfactants and hydrocarbon-based solvents that break up oil into smaller droplets that are easier to dissolve or degrade. In past oil spills, workers in airplanes or boats sprayed dispersants onto surface oil slicks. During the Deepwater Horizon spill, scientists reasoned that applying a jet of dispersant at the spill's source, 1,500 meter below the surface, could prevent large oil droplets from rising and forming oil slicks, which can cause significant damage to coastal environments.

At high concentrations, dispersants can be toxic to marine life. So Elizabeth Kujawinski, a chemist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and colleagues wanted to know what happened to the chemicals in the deep sea. During and after underwater applications, her team collected water samples at different depths around the Deepwater Horizon wellhead to track the anionic surfactant dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate (DOSS), a major component of the dispersant Corexit 9500A and 9527. The researchers then developed an extraction technique to concentrate DOSS from large volumes of seawater before detecting and quantifying the chemical with mass spectrometry.

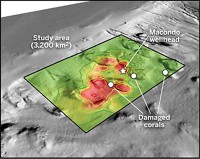

Sixty-four days after deep-water applications ceased, DOSS concentrations were 3 to 6 ng/L in waters about 300 km away from the wellhead. These concentrations suggest that the chemical barely degraded over those two months, Kujawinski says. "We were surprised to see the molecule persisting as long as it did, both in terms of time since the spill and distance from the wellhead," says Kujawinski. She notes that previous studies disagree over whether microbes can degrade DOSS or seawater can hydrolyze it.

In the seawater samples, the researchers detected chemical signatures of oil and gas at the same depth as DOSS, about 1,000 to 1,200 meter below the surface. From this observation, they concluded that the surfactant spread with the oil plume as it diffused from the wellhead. But the scientists couldn't determine whether DOSS had interacted with the oil to form tiny droplets—as spill responders had hoped it would--or it had just partitioned into the plume.

Kujawinski lessens worries about the persistence of the dispersant by saying that toxicological studies in coastal organisms indicate that harmful levels of DOSS are about 1000 times higher than those her team found. However, she adds that little data exist on the effects of chronic, low-level DOSS exposures to deep-sea organisms.

Jacqueline Michel, President of Research Planning, Inc., a consulting firm involved with the oil spill response, says, "This study helps us understand the fate and potential effects of dispersant use in deep water, which will inform decision making for future responses."

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter