Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Policy

China's Journals Embrace English

Number and influence of English-language chemistry publications from China climb

by Shawna Williams, Contributing Editor

February 21, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 8

China’s increasingly high-powered research is beginning to be matched by its English-language journals, which are growing in both numbers and international prominence.

R&D spending in China shot from $10.8 billion in 2000 to $66.5 billion in 2008, according to “UNESCO Science Report 2010.” The number of scientists and engineers in the country more than doubled over the same period, to 1.59 million. Generally, these scientists must publish a certain number of papers to graduate with a Ph.D., get a job in academia, and be promoted. Many Chinese universities further specify that qualifying papers must be published in journals that meet the quality standards for indexing in the Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE) and thus earn an annual impact factors that can be used to compare how often competing journals are cited. Some universities even peg bonuses to the impact factors of the journals a scientist publishes in.

This combination of funding and pressure has brought a steep rise in Chinese-authored publications. The percentage of chemistry papers in SCIE journals with at least one China-based author rose from 9.3% in the 1999–2003 period to 16.9% in 2004–08, reports Thomson Reuters, the company behind SCIE.

Some of these papers are published in Chinese-language journals, but authors often prefer to reach a broader audience by submitting to English-language journals outside the country. A third, increasingly attractive option for Chinese and non-Chinese scientists alike is to publish in an English-language journal based in China.

For Chinese scientists, especially those unused to navigating the publication process of international journals, domestic English-language journals can provide help. “A lot of international journals haven’t figured out how to be author-friendly to nonnative English-speaking authors, or authors from emerging markets,” says Benjamin Shaw, global and China director at Edanz Group, which provides editing and training for authors and journals. “If the language hasn’t met a minimum level, the paper is rejected, and the author just has to fix it.” By contrast, he says, English-language journals in China have found that “by being more flexible with language, they can pick up good science.” Journals then take responsibility for cleaning up the English before publication.

Submitting a paper to a domestic journal also makes communication easier, says Jun Yan, a chemistry graduate student at Chongqing University. For example, submitting to a foreign journal requires writing a cover letter and e-mails in English, he says, whereas he can quickly contact editors in China by phone.

Domestic English-language journals can thus smooth the path toward communicating Chinese research results to international readers, a major reason that most editors cite for publishing in a foreign language. But using English is just one step toward gaining international visibility.

One challenge facing English-language journals from China is common to many new publications: They need to publish high-quality articles to raise their impact factors and visibility, but scientists prefer to submit their best work to journals that already have attained high profiles. Breaking out of this cycle “is really hard, especially when these journals are competing with prestigious journals that already have a high impact factor,” says Becky Zhao, an editor at Springer’s Beijing office who works with engineering journals.

Although most Chinese chemists who spoke with C&EN said they wished to see their country develop world-class journals, they cited drawbacks to submitting locally, notably Chinese journals’ tendencies to have relatively low impact factors and long lags between submission and publication, and to charge submission and page fees. “In general, the professors in good universities like to submit to foreign journals,” although students may be more open to publishing within China, observes Quan Zhu, a chemistry lecturer at Sichuan University. In his own research group, he says, “We devote a lot of effort to English papers, so our first hope is to publish in foreign journals.”

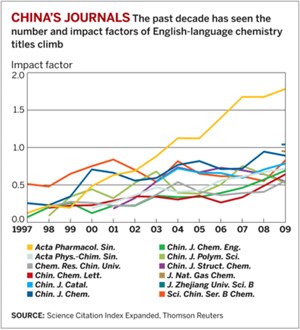

Not everyone agrees; several chemistry professors told C&EN they choose to submit to a journal on the basis of subject matter and impact factor, regardless of where it is published. And the commonly cited drawbacks to publishing in China do not apply to all journals there. The number of China-based English-language chemistry journals in SCIE has climbed from seven in 1999 to 12 in 2009. Most of these journals still have impact factors of less than 1, but the impact factors, too, are rising. Zhao points to the success story of Nano Research, launched in 2008 by Beijing’s Tsinghua University. The journal’s first impact factor, for 2009, was 4.37, placing it in the top 20% of SCIE-indexed physical chemistry journals.

So how do journals like Nano Research break out of the cycle? It’s vital that publications draw international readers and contributors, both because international diversity is a key factor in admission to SCIE and because Chinese scientists want their English-language publications to reach overseas audiences. In recent years, many Chinese journals have partnered with international publishers such as Elsevier and Springer, Shaw says. Zhao confirms that since entering China in 2005, Springer has collaborated with more than 90 journals there. In addition to providing a platform, the company helps journals get into abstracting and indexing services and gives editors tips on such steps as attracting international board members and contributors. One way for publications to quickly increase their visibility, she says, is by adopting an open-access model.

Editors may also need coaching in basics such as following ethical norms, building a high-quality website with clear instructions for authors, improving language quality, ensuring that papers cite conflicting research, and including good abstracts, tables, and figures, Shaw says. As more editors recognize the need for such improvements, China’s English-language journals are “definitely getting better; I think in the past one-and-a-half to two years, they’ve entered the next stage of evolution,” he says.

Most still have significant work to do if they are to become true international contenders. Brian D. Crawford, president of the Publications Division of the American Chemical Society, which publishes C&EN and 39 scientific journals, says that although the past decade has seen a 10-fold rise in the percentage of Chinese-authored articles in ACS journals, there are as yet no Chinese journals he would consider “specific competitors.”

But some foreign authors are taking notice of China’s journals. A perusal of English-language chemistry journals based in China turns up a smattering of non-Chinese authors, mainly from other Asian countries such as Iran, India, and Malaysia. Junli Wang, an editor at Chinese Chemical Letters, notes that 32% of submissions to that journal now come from outside China, most from Central Asia. The journal’s top goals, he says, are to elevate its impact factor to 1, increase the number and diversity of contributors from abroad, and attract higher quality submissions.

The Chinese government also has plans to bring the quality of the country’s journals in line with its research output. Most Chinese journals are sponsored by individual universities or research institutes, and having so many small-time publishers “makes resource integration and scale efficiency impossible,” Dongdong Li, vice minister of state and deputy director of the General Administration of Press & Publications, said in a speech at a periodicals conference on Dec. 6, 2010. Furthermore, these journals put out too many “incremental publications with poor academic quality,” she said. Without going into details, she explained that to solve these problems, her agency will form large publishing groups where higher quality journals can cooperate, strengthen training and requirements for editors, and establish a comprehensive quality evaluation system for journals.

As far as China’s English-language journals are concerned, another factor may be just as important to future success: Chinese scientists’ growing English abilities. Bingfeng Pan, an editor at the Chinese Journal of Chemistry, relates that when the journal first switched languages in 1990, it got few submissions, and those required heavy editing. Now, he says, “the English level of contributors in China has improved a lot, and they are already used to writing papers in English.”

Shawna Williams is a freelance journalist based in Chengdu. Additional reporting was done by Xiongfei Pan.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter