Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Synthesis

That's How Breast Cancer Cells Roll

Cancer Biology: A glycoprotein allows breast cancer cells to roll on blood vessels and invade other tissue

by Jeffrey M. Perkel

January 13, 2011

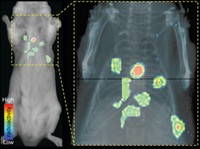

When cancer metastasizes, cells break off from the primary tumor, travel through the lymphatic or circulatory system, and then invade other tissue. Now researchers have found a protein that allows breast cancer cells to roll along blood vessel walls—a key step in the metastatic process (Anal. Chem., DOI: 10.1021/ac102901e).

Cancer cells take a page from white blood cells' playbook when it comes to tissue invasion. When responding to an injury, leukocytes cling loosely to the cells lining a blood vessel wall and then, propelled by the shear force of the rushing fluid, roll along it like Velcro-covered soccer balls. They continue until they can attach tightly enough to worm their way between the wall's cells and into the surrounding tissue. To perform these cellular acrobatics, two proteins must interact: selectins, which protrude from vessel wall cells, and their ligands, which leukocytes and circulating tumor cells express on their surfaces.

To date, scientists have discovered a handful of ligands for one type of selectin called E-selectin. But no one had yet found its ligands on the widely studied breast cancer cell line MCF-7. So Seungpyo Hong and David Eddington of the University of Illinois, Chicago, and colleagues went looking for one.

They focused on a cell-surface glycoprotein called CD24, which appears on a number of solid-tissue metastatic cancers and cell lines, including MCF-7, and whose expression levels generally correlate with lower survival rates in patients. "CD24 is extremely important for cancer cells, in a bad way," Hong says.

Using surface plasmon resonance, the researchers determined first that E-selectin binds CD24 about 20 times more tightly than it does a known ligand, sialyl Lewis X. Next, using live cells they showed that blocking CD24-selectin binding with a CD24 antibody prevents MCF-7 cells from rolling on an E-selectin-coated surface. Finally, by coating 10-μm microspheres with CD24, the team showed that it alone allows adhesion to E-selectin surfaces. CD24 is the key E-selectin ligand on MCF-7 cells, Hong concludes, but its influence may be broader than that: His lab is investigating the protein in connection with other cancer cell types, as well.

If CD24 does prove to be a critical metastatic player, Hong envisions blocking its interaction with E-selectin as a means to limit metastasis. But Udo Schumacher of the University of Hamburg, in Germany, who studies the link between selectins and metastasis, has doubts. Breast cancer metastasis, he says, occurs relatively early, sometimes before doctors can detect the primary tumor. That would make Hong's approach akin to shutting the barn door after the horses have gone, Schumacher says. Nevertheless, he says, "I think the data are very interesting and worth following up."

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter