Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Analytical Chemistry

Why Van Gogh's Yellows Lose Their Luster

Art Analysis: X-rays reveal chemical degradation that causes yellow paint in the artist's masterpieces to darken with time

by Laura Cassiday

February 18, 2011

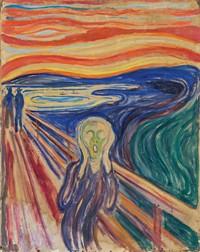

In 1888, while painting his famous Sunflowers series, Dutch artist Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother, "I am working every morning from sunrise on, for the flowers fade so quickly." Little did van Gogh know that his painted sunflowers would suffer the same fate, the vibrant yellow hues obscured over time with a brown patina. Now, using X-ray spectromicroscopy, European researchers have uncovered the chemical source of the mysterious brown layer—the first step toward preventing further deterioration of the paintings (Anal. Chem., DOI: 10.1021/ac102424h, 10.1021/ac1025122).

In the late 19th century, van Gogh and other artists experimented with bold new paint colors made available by improved industrial synthesis. Among these was chrome yellow, a bright yellow pigment made of lead chromate (PbCrO4). By the 1950s, artists had abandoned chrome yellow in favor of less toxic, more stable alternatives. Yet art aficionados and chemists alike remained curious about how chrome yellow degrades to form a thin brown layer and, perhaps more important, how to slow or stop the process.

Because the brown layer is only 1 to 3 μm thick, conventional methods lack the spatial resolution needed to discriminate chemicals in this layer from those in the underlying yellow paint. "We wanted to see whether, with modern means of nondestructive analysis, we could shine some light on this problem, both figuratively and literally," says Koen Janssens, a chemist at the University of Antwerp in Belgium.

So Janssens and his colleagues examined the degradation process of lead chromate using intense X-ray beams produced by the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in Grenoble, France. The synchrotron produces bright X-ray beams 100 times thinner than a human hair, allowing the researchers to specifically probe the composition of the miniscule brown layer.

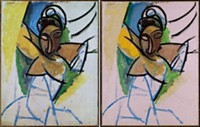

In the first part of their study, the team characterized the degradation process in three leftover paint tubes from van Gogh's artistic contemporaries. The researchers squeezed chrome yellow paint from the tubes and spread a thin layer on a microscope slide. Then, they artificially aged the samples with an ultraviolet lamp. The surface of one sample, from an early 20th century paint tube belonging to Flemish artist Rik Wouters, showed substantial darkening compared to the other paints.

With a suite of X-ray spectroscopy techniques, the investigators linked the darkening of the top layer of Wouters' paint to the chemical reduction of chromium from chromium(VI) to chromium(III) and the formation of the green pigment Cr2O3•2H2O. Sulfates promoted the degradation, which explains why only Wouters' paint sample, which is rich in lead sulfate, showed substantial darkening.

In the second part of the study, conservators of the van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam provided tiny chrome yellow fragments from two of van Gogh's paintings, Banks of the Seine (1887) and View of Arles with Irises (1888). Janssens and colleagues demonstrated that the same chemical process they observed in paint samples also takes place in actual paintings. Van Gogh's tendency to blend a sulfate-containing white pigment with his yellow paint may have hastened the degradation process, Janssens speculates. His team is now undertaking a systematic study of the effects of temperature, light, and paint composition on chromium reduction to figure out how best to slow the degradation.

Francesca Casadio, a conservation scientist at The Art Institute of Chicago, calls the study "a major leap forward in designing optimal conditions for painting preservation." She applauds the interdisciplinary collaboration between scientists and museum conservators. "This study shows that cultural heritage science has matured to a field that pushes the boundaries of what analytical techniques can do today."

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter