Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Analytical Chemistry

Cheap, Simple Test Spots Protein-Protein Interactions

Biological Assay: Using graphene oxide, a new method could help researchers find peptide-based drugs

by Erika Gebel

September 26, 2011

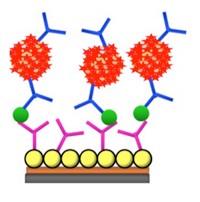

A graphene oxide-based assay could provide chemists with an inexpensive means to detect protein-protein interactions (Anal. Chem., DOI: 10.1021/ac200617k).

To discover peptide-based drug candidates, researchers often monitor how a disease-related protein interacts with libraries of small peptides. The biggest challenge is developing an easily measurable signal for when the proteins bind to peptides, says Chun-Hua Lu of Fuzhou University, in China. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) spectroscopy, which monitors the distance between fluorescent molecules attached to the proteins, is commonly used, but to generate a signal, it often requires a protein to change shape upon binding. To study proteins that don’t shape shift, Lu and his colleagues developed a more general approach.

To the end of a peptide, the researchers attach pyrene and measure its fluorescence with a spectrometer. Then, they mix the tagged peptide with graphene oxide, which pyrene binds to. Graphene oxide, made from the same inexpensive graphite at the core of most pencils, quenches the fluorescent signal from the pyrene-bound peptide when pyrene stacks onto its flat surface. Finally, the researchers add the protein of interest. If it binds to the peptide, the tagged peptide leaves the graphene oxide and the fluorescent signal returns.

The team tested the assay with a well-studied system: a peptide that is a hallmark of HIV infection along with a human antibody that binds it. They found that as little as 200 pM of the antibody rekindled pyrene’s glow.

To test their method further, the researchers next applied the antibody in samples of human saliva and serum, which contain molecules that could disrupt the protein-peptide interaction. Even with the additional chemicals present, the assay had detection limits of 2 nM in saliva and 5 nM in a solution made from human serum. These limits match those of existing methods, Lu says.

To test their method with other protein-peptide pairs, the researchers successfully detected binding between different peptides and a second HIV antibody, as well as with a protein called α-bungarotoxin from snake venom.

Kevin Plaxco of the University of California, Santa Barbara, is “cautiously optimistic” about the new assay. Since Lu’s team looked at three different protein-peptide systems, he says the method probably works more broadly, but he thinks more research is needed to prove it.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter