Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Safety

Biosecurity: An Evolving Challenge

Scientific advances have increased the risk of a biological terror attack

by Glenn Hess

February 13, 2012

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 90, Issue 7

U.S. biodefense officials say they are satisfied with the outcome of a recent global conference: Participating nations agreed to increase cooperative efforts to combat the growing threat posed by terrorist groups that seek to obtain and use biological weapons.

But some arms control experts assert that much more aggressive action is needed by the international community to boost security and reduce the potential for a major bioterror attack somewhere in the world.

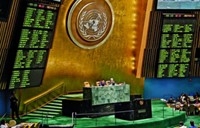

Representatives of the 165 governments that have ratified an international agreement to ban biological weapons gathered in Geneva in December 2011 to review and update the nearly 40-year-old accord. Only 23 countries have not signed the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC), among them Israel, Kazakhstan, and several African nations.

Bioweapons Control

1969 President Richard M. Nixon declares that the U.S. unconditionally renounces all methods of biological warfare. The U.S. biological program will be confined strictly to research on defensive measures.

1970 The U.S. extends its ban on biological weapons to include toxins, which are agents produced through biological processes.

1972 The U.S., Britain, and the Soviet Union sign the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC). Parties to the convention agree not to develop, produce, stockpile, or acquire biological agents or toxins that have no peaceful purpose. BWC does not prohibit research and does not contain provisions to verify compliance.

1975 The U.S. ratifies BWC. By the end of the year, the U.S. announces that it has completed the destruction of all biological weapons.

1986 BWC review conference adopts several “politically binding” confidence-building measures, including the declaration of all high-security containment facilities and the encouragement of the publication of research results.

1990 President George H. W. Bush signs the Biological Weapons Anti-Terrorism Act, making it illegal for the U.S. to develop or possess biological weapons. The legislation completes U.S. implementation of BWC.

1991 BWC review conference creates a group of governmental experts to “identify measures which would determine whether a state party is developing, producing, stockpiling, acquiring, or retaining” biological weapons.

1992 Russian President Boris Yeltsin announces the end of Russian biological weapons research.

2001 The U.S. rejects a draft protocol to bolster the convention through on-site inspection of relevant facilities. The negotiations collapse and have not resumed.

2012 To date, BWC has been ratified by 165 countries. An additional 12 states have signed the pact but have yet to ratify it.

SOURCE: Federation of American Scientists

The Cold War-era treaty, which entered into force in 1975, was the first multilateral disarmament treaty to ban the production of an entire category of weapons. Specifically, it prohibits the development, production, stockpiling, and transfer of biological weapons, as well as biological agents and toxins “that have no justification for prophylactic, protective, or other peaceful purposes.”

It also requires parties to the convention to destroy all relevant “agents, toxins, weapons, equipment, and means of delivery” and to take steps to prevent the acquisition or use of biological weapons by individuals. The agreement does allow biological research for defensive purposes, such as immunization.

To emphasize the U.S. government’s growing anxiety about the risk of biological terrorism, Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton addressed the Geneva conference. Her appearance marked the first time such a high-ranking U.S. official appeared at a BWC review forum, an event that is held every five years.

Clinton told those attending the two-and-a-half-week conference that the threat of a bioweapons attack was “both a serious national security challenge and a foreign policy priority.” She said the same rapid advances in science and technology that are making it possible to prevent and cure more diseases are also making it easier for both groups and countries to develop artificial viruses and bacteria.

“Unfortunately, the ability of terrorists to develop and use these weapons is growing. Therefore this must be a renewed focus of our efforts,” Clinton said. “Terrorist groups have made it known they want to acquire these weapons.”

Clinton pointed out that a crude but effective terrorist weapon can be made by using a small sample of any number of widely available pathogens, inexpensive equipment, and “college-level chemistry and biology” training. Even as it becomes easier to develop these weapons, she said, “it remains extremely difficult to detect them.”

Chemical and biological agents have been used in attacks on civilians before, Clinton noted, citing the sarin gas attack on the subway system in Tokyo in the 1990s and the anthrax attacks in the U.S. that killed five people and sickened 17 others in 2001.

In 2001, she said, the U.S. military found evidence in Afghanistan that al-Qaeda was seeking the ability to carry out bioweapons attacks. “And less than a year ago, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula made a call to arms for, and I quote, ‘brothers with degrees in microbiology or chemistry to develop a weapon of mass destruction,’ ” Clinton noted.

To bolster confidence that all countries are living up to their obligations under the treaty, Clinton said the convention’s annual reporting systems should be revised so that member nations more clearly explain what they are doing to guard against the potential misuse of biological materials. Participating governments should also be willing to make more information publicly available and open their facilities to outsiders, she added. But the U.S. will continue to oppose an international verification and inspection system, Clinton said.

Unlike with other arms control agreements, such as those addressing nuclear and chemical weapons, compliance with BWC’s obligations is not monitored by an international organization. Instead, the accord relies on optional measures, such as voluntary reporting by member nations, to build confidence that biological R&D activities have no warfare component.

The U.S. has long opposed efforts by other countries—including some U.S. allies—to create a formal system to verify compliance, similar to the program run by the International Atomic Energy Agency, which tracks nuclear materials. Negotiations on a verification regime for BWC collapsed in 2001 after the U.S. rejected a draft protocol, arguing it would put national security at risk.

At the Switzerland conference, Russia’s deputy minister of foreign affairs, Gennadiy M. Gatilov, renewed the call for a mandatory verification and inspection system, asserting that such a protocol is necessary because “ordinary transparency measures, with all their importance and usefulness, cannot give such certainty.”

However, the U.S. maintains that it would be extremely difficult to monitor compliance because genetic engineering is used for legitimate purposes such as vaccine production and research on how bacteria and viruses cause diseases. Consequently, a biological weapons program could easily be hidden within legitimate activities.

“A traditional verification mechanism, as employed in other arms control agreements, would not have the desired effect of strengthening the convention when it comes to biological weapons,” says Thomas M. Countryman, the State Department’s assistant secretary for international security and nonproliferation.

Inspection and monitoring programs used for verifying international compliance with traditional arms control agreements are inappropriate for biological weapons for various reasons, according to Countryman, a career foreign service officer.

“Biological science is too broad a category, with both knowledge and materials too diffuse ... . So you can’t identify the facilities that would need to be verified,” he remarks.

Detecting illicit or potentially prohibited activities would also be virtually impossible, Countryman says. In the life sciences, he notes, “almost everything is dual use. And to identify techniques that are applicable only to weapons or only to peaceful uses is, in fact, impossible.”

The “sheer number of places where research is done, and the degree of intrusiveness that would have to be undertaken to make it work, I think, precludes an effective verification technique,” Countryman asserts, “So we do not have any ideological objection, but we do have a practical objection to a verification mechanism.”

The U.S., he says, will continue to emphasize so-called confidence-building measures as a means of encouraging compliance with BWC. Such measures include voluntary public declarations of specific substances used in research laboratories, identifying the labs that are engaged in permitted biological activities, and divulging the outbreak of diseases that might raise suspicions regarding compliance with BWC.

“Not only can these help give states the confidence that the convention is being upheld, but we can—even if we don’t agree on this point—move forward on the basis of consensus on other steps that will make the convention even more effective,” Countryman says.

In Geneva, member nations ultimately agreed to revise BWC’s voluntary annual reporting system to be more transparent about their efforts to guard against the misuse of biological materials. Currently, only about half of the signatory countries file reports on their biological activities, according to the State Department.

“The conference recognizes the urgent need to increase the number of states parties participating in confidence-building measures and calls upon all states parties to participate annually,” diplomats said in a joint statement at the end of the meeting. “State parties” refers to all countries belonging to the treaty.

Diplomats also called on “those states parties, in a position to do so, to provide technical assistance and support, through training for instance, to those states parties requesting it to assist them to complete their annual confidence-building measures submissions.”

Countryman says the U.S. is happy with the results of the meeting. “We think they are significant for not only the U.S. as we move ahead on advancing the President’s national strategy for countering biological threats, but that they have the same value for all of our partners around the world who share this concern about potential biological and toxic threats,” he remarks.

Some bioweapons experts are skeptical, however, that increased transparency in the life sciences sector can ensure compliance with BWC. “The review conference did succeed in strengthening the convention’s confidence-building measures, but that’s like saying that repairing a leaking pipe on the Titanic strengthened it against water damage,” says Barry Kellman, professor of international law and director of the International Weapons Control Center at DePaul University in Chicago.

Confidence-building measures, Kellman observes, are an exercise in multilateral exchanges of mutual good faith, important in the symbolic sense of conveying respect for BWC process. But the information in the declarations “contains almost nothing from the perspective of actually knowing who might be producing biological weapons,” he says.

“Indeed, I know of no expert who can point to a data set that would actually contribute to the detection of wrongful conduct,” Kellman remarks. The treaty’s confidence-building measures are a “sideshow,” he adds. “If the bioweapons-Titanic ever hits an iceberg, it’s all irrelevant posturing.”

On the other hand, Amy Smithson, a senior fellow at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies in Washington, D.C., says she is disappointed that members didn’t do more to enhance the treaty’s confidence-building provisions.

“By only slightly adjusting some declaration forms, sidestepping the necessity to increase transparency in critical areas—such as biodefense programs—and failing to chart a course to make the declarations mandatory, BWC’s membership showed a lack of seriousness about strengthening the treaty,” Smithson tells C&EN.

Smithson also says she would like to see participating governments revive negotiations over verification and inspection options for the treaty. “Many BWC members, including the U.S., find it convenient to repeat a mantra dating back over 40 years that the treaty is ‘unverifiable,’ ” she says.

In the 1990s, Smithson points out, inspectors from the United Nations Special Commission overcame considerable odds to uncover Iraq’s covert biological weapons program. “If BWC’s members would do their homework and learn from this experience, they may recognize that inspections can distinguish legitimate, peaceful facilities from those masking illicit activities,” she remarks.

“Refusing to engage in talks to explore the capabilities and limitations of inspections indicates that confirming compliance with BWC’s prohibitions is not a priority and constitutes a grave disservice to the interests of international peace and security,” Smithson declares.

Unlike Smithson, Kellman says he agrees with the U.S. position that a verification regime for bioweapons is not feasible. “It’s frankly difficult to believe that people keep talking about this. There’s no support within the U.S. government or serious expert communities for a verification regime,” he says.

An array of mechanisms could be put in place that would make humanity safer from the threat of bioweapons, Kellman says. “But a system that is extraordinarily expensive for complying states and easy to deceive for noncomplying states—or nonstate actors—is not among those useful mechanisms,” he asserts.

Instead, Kellman recommends actions such as developing a database of worldwide labs that are working with dangerous pathogens and requiring security measures to guard against wrongful access. In addition, he says a global stockpile and distribution system for medical countermeasures should be developed, and steps should be taken to ensure that intentional infliction of disease is a crime that can readily be prosecuted in national and, if appropriate, international courts.

“None of these ideas will eliminate the threat by itself, but in combination they can make bioattacks substantially more difficult and less effective from the perpetrators’ perspective,” Kellman says. He adds that all of these initiatives could be accomplished for little cost and without significant intrusion into legitimate science or diversion of public health resources.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter