Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

As Acid Rain Drops, Water Can Become Too Clean

Pollution: In a New Hampshire forest, getting back to “normal” may not be possible

by Naomi Lubick

April 13, 2012

For decades, researchers have watched the response of a small forest in New Hampshire to reductions in acid rain. The data largely suggest recovery. But they also hint that the water flowing through streams in the ecosystem could end up “distilled” – barren of salts that are necessary for life to thrive there, according to new research (Environ. Sci. Technol., DOI: 10.1021/es3000189).

Researchers have monitored the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest since the 1960s. Acid rain in the northeastern U.S. diminished after measures taken in 1970 under the Clean Air Act cleaned up power plant emissions.

But after pollutants in precipitation decreased, researchers at Hubbard Brook noted another disappearance: beneficial cations. Gene Likens and Donald Buso of the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, a private environmental research organization, looked at monitoring data collected from 1969 to 2009 in a watershed within the site; they saw a steady decline of cations such as calcium and magnesium in the surface waters.

When the measurements started in the 1960s, electrical conductivity levels that measure the amount of ions in water were about 25 microsiemens per cm in the network of streams. Then acid rain deprived the soil of its cations, the researchers say, and the result was that the streams’ electrical conductivity in 2009 was only 10 μS per cm. They project it to drop to 5 μS per cm by 2025, close to the conductivity of distilled water available from a grocery store. The conductivity is already surprisingly low, comments Jill Baron of the U.S. Geological Survey, who was not involved in the study.

Calcium in particular dropped, depriving the watershed of its buffer – its “Tums and Rolaids,” Likens says – against acid rain. With so little buffer, acid rain falling today in tiny amounts has a large impact, he says. For example, it may increase the release of aluminum from soils, which then could harm trees in the watershed. In the past few decades, he and other researchers have observed that trees in the watershed are not growing, Likens says.

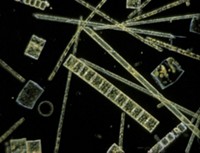

The water will soon be too clean, Likens says, a condition whose broad ecological impacts have yet to be studied. Hints of those impacts have emerged from a handful of studies in Norway that suggest that low-ion conditions in mountain lakes harm young brown trout (Water, Air, Soil Pollut., DOI: 10.1007/s11270-010-0722-4). Insects that use calcium to build their shells might also suffer, Baron suggests, including daphnids, which form an important lower rung on ecosystems’ food chains.

The researchers warn that other locations may soon also witness low ion concentrations in surface water and precipitation.

The Hubbard Brook data also highlight a difficulty ecologists constantly face, says Kevin Bishop of the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences: Determining the “natural baseline” of an ecosystem remains difficult. Perhaps this forest will never return to how it was before, he adds.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter