Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

Small Audience, Large Payoff

The current groundswell of interest in rare diseases can be traced to Genzyme, the first firm to show that drugs for small patient populations could be profitable

by Lisa M. Jarvis

May 13, 2013

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 91, Issue 19

Anyone puzzling over the business case for developing drugs for tiny patient populations need look no further than Genzyme. Founded in Boston in 1981, the biotechnology firm pioneered the model for rare disease drug development that is followed today: make an impact on a previously untreated rare disease, charge high prices, and be rewarded with significant revenues and a long reign in the marketplace.

Genzyme made its mark by introducing the first treatment for Gaucher’s disease, a lysosomal storage disease caused by a deficiency in the lipid-busting enzyme glucocerebrosidase. Similar to Hunter syndrome, Gaucher’s occurs when the absence of that key enzyme causes a buildup of molecules in the lysosome and results in a variety of problems. Complications from Gaucher’s include enlarged organs, bone pain, and anemia.

When Genzyme embarked on developing an enzyme replacement therapy for type 1 Gaucher’s, which does not affect the central nervous system, the disease was thought to affect just 1,500 people worldwide. Conventional wisdom at the time was that a company could not turn a profit on a drug for such a minuscule patient population.

To download a PDF of this article, visit http://cenm.ag/raredisease.

But the naysayers were proven wrong. The Food & Drug Administration approved the drug in 1994, and Genzyme charged an unprecedented $200,000 per year. Although insurance companies balked at the cost, they eventually agreed to cover it. Companies like Genzyme ensured patient access by introducing assistance programs that helped families with potentially high copays.

With a treatment on hand, the diagnosed patient population more than tripled, reaching roughly 5,000 people, industry watchers say. Moreover, Genzyme had a captive audience: The first competition for its drug, Cerezyme, didn’t arrive until 2010, when Shire won approval to sell a rival, Vpriv. At their peak in 2008, annual sales of Cerezyme reached $1.2 billion.

The success of that model—a small, genetically defined patient population and a high-priced drug—spawned two other companies that continue to be mainstays in the rare disease arena: Transkaryotic Therapies, founded in Cambridge, Mass., in 1988 and acquired by Shire for $1.6 billion in 2005, and BioMarin Pharmaceutical, started in 1997 in Novato, Calif. Together, Genzyme, Shire, and BioMarin have gone on to develop some of the most expensive drugs—all enzyme replacements.

Those three firms laid the foundation for the current corporate interest in rare diseases. Alumni from Genzyme now populate the executive suites of many of the companies focused on rare diseases. Notably, the chief executive officers of Aegerion Pharmaceuticals, Amicus Therapeutics, Prosensa, and Synageva BioPharma all had stopovers at Genzyme.

But all this activity isn’t just about high premiums, says Christopher P. Austin, director of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. “I think people have really internalized the concept that rare diseases are a window into common diseases,” Austin says. Rare genetic disorders occur when a gene is completely turned off; more common diseases often happen when that same gene’s function is simply turned down.

He points out that the first scientific clue in the development of cholesterol-lowering drugs like Pfizer’s Lipitor—for years the world’s best-selling drug—was the discovery of a cluster of families with a rare, genetic mutation that causes very high levels of “bad” cholesterol.

GROWING INTEREST

Deals To Develop Rare Disease Therapies Have Proliferated In The Past Three Years

October 2009: In a pact worth up to $680 million, GlaxoSmithKline and Prosensa team to develop RNA-modulating therapies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

December 2009: Pfizer agrees to pay Protalix Biotherapeutics up to $115 million for worldwide rights to taliglucerase alfa, to treat Gaucher's disease.

February 2010: GSK launches a unit dedicated to developing treatments for rare diseases.

March 2010: GSK and Isis Pharmaceuticals establish a pact to develop antisense therapies for rare diseases.

June 2010: Pfizer establishes a dedicated rare disease unit.

September 2010: Pfizer acquires FoldRx Pharmaceuticals, which brings a portfolio of compounds to treat diseases caused by protein misfolding.

October 2010: GSK, the Telethon Foundation, and the San Raffaele del Monte Tabor Foundation join to develop gene therapies for rare genetic disorders.

October 2010: GSK partners with Amicus Therapeutics to develop Amigal, a small molecule to be used with enzyme replacement therapy for Fabry disease.

February 2011: Sanofi agrees to acquire Genzyme for $20.1 billion.

April 2011: The International Rare Diseases Research Consortium is established to help coordinate global efforts in rare disease research.

November 2011: Agios Pharmaceuticals raises $78 million to support a research effort around inborn errors of metabolism.

November 2011: Roche pays $30 million for worldwide rights to PTC Therapeutics' spinal muscular atrophy program.

December 2011: Shire and Atlas Venture team to identify and invest in early-stage rare disease therapeutics.

February 2012: GSK pays Angiochem $31.5 million as part of a deal to develop compounds that can cross the blood-brain barrier and treat lysosomal storage diseases.

June 2012: Roche and Seaside Therapeutics agree to jointly develop mGluR5 antagonists for the treatment of fragile X and autism spectrum disorders.

July 2012: Sanofi and Spain's Centre for Genomic Regulation sign a three-year research collaboration that emphasizes genetic and rare diseases.

November 2012: Shire and Boston Children's Hospital sign a three-year research pact to develop treatments for rare pediatric diseases.

November 2012: Pfizer and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation establish a six-year preclinical research program to find drugs for people whose CF is caused by the ΔF508 mutation.

January 2013: Shire buys Cambridge, Mass.-based Lotus Tissue Repair, gaining a protein replacement therapy for the treatment of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa.

January 2013: BioMarin Pharmaceutical acquires Zacharon Pharmaceuticals, gaining small molecules to block heparan sulfate synthesis for mucopolysaccharidosis disorders and ganglioside synthesis inhibitors for Tay-Sachs disease.

February 2013: Roche pays Chiasma $65 million up front for the rights to Octreolin, a peptide in a Phase III trial for acromegaly, a rare hormonal disorder.

February 2013: The European Commission sets aside $187 million in funding for 26 rare disease projects.

March 2013: Shire acquires Premacure, gaining a protein replacement therapy for a rare eye disease that primarily affects premature infants.

April 2013: Roche pays Isis $30 million as part of deal to develop antisense drugs to treat Huntington's disease.

April 2013: New Enterprise Associates and Pfizer Venture Investments lead a $16 million round of financing to launch Cydan, an orphan drug accelerator.

SOURCE: Companies

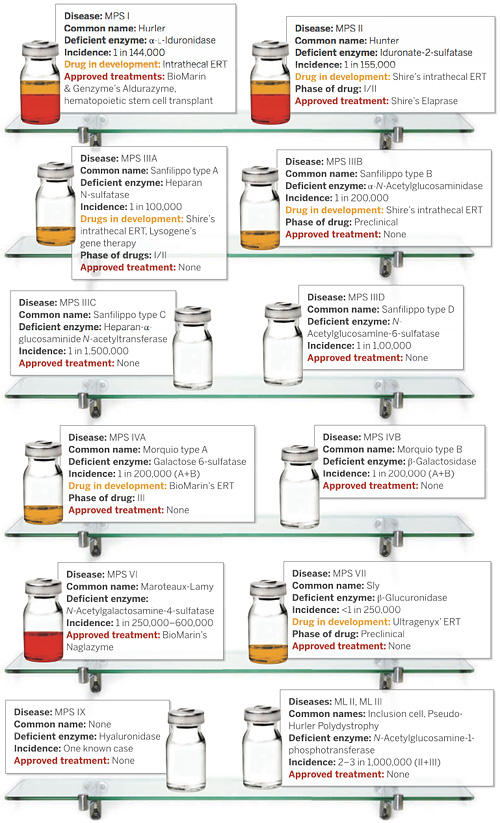

Rare disease advocates have taken that concept to heart. Hunter syndrome belongs to a collection of more than a dozen diseases, each caused by a deficiency in a different sugar-busting enzyme. Many of these so-called mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS) diseases primarily affect the brain, and patient groups trying to win funding for MPS research often point to the connection between MPS diseases and common neurological disorders.

In 2009, for example, University of California, Los Angeles, scientists discovered that children with a type of MPS disease called Sanfilippo syndrome produce high levels of tau, one of the two telltale proteins found in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease.

The link means that better understanding the mechanism of Sanfilippo could lead to treatments for Alzheimer’s. At a recent lobbying day for rare disease advocates, Jill Wood, a mom from Brooklyn whose son has Sanfilippo type C, also known as MPS IIIC, tried to impress upon her local congressmen that although Sanfilippo research might directly affect only a few dozen children in the U.S., the greater good for society makes it a worthwhile investment.

Congressional staffers’ eyes clouded when Wood uttered words like mucopolysaccharidosis. They sat up and listened when she said Alzheimer’s.

Although rare diseases could open the door to treatments for common ailments, the flip side is that common diseases are starting to be segmented into smaller subpopulations on the basis of genetics. “The paradigm for orphan drug development today may become the paradigm of more common drug development tomorrow,” says Philip J. Vickers, global head of R&D for Shire’s rare disease unit.

Industry experts like to hold up lung cancer as an example of this shift. As scientists pick apart the different biological drivers of lung cancer, they can provide more personalized treatments for the nearly 230,000 people diagnosed with the disease each year.

Pfizer’s Xalkori, a drug designed to treat roughly 7% of lung cancer patients whose disease is caused by a mutation in the ALK gene, illustrates how segmenting can be profitable. Because the drug makes such a dramatic impact on patients’ survival, Xalkori reached the market just four years after the discovery of the ALK mutation. Clear efficacy data and a small patient population enabled Pfizer to slap a $9,600 monthly price tag on the treatment. Consultancy firm EvaluatePharma expects that Xalkori will bring in more than $900 million in annual sales by 2018.

“Rare diseases in some ways set a template for the future,” says Kevin Lee, chief scientific officer of Pfizer’s rare disease group. “We believe we’re going to learn far more about some of these basic diseases, which will allow us to segregate them much more specifically by molecular mechanism. Ultimately, these large diseases will become constellations of many small diseases, all of which have the same symptoms.”

Meanwhile, scientific understanding of rare diseases has grown by leaps and bounds. Although the Human Genome Project failed to deliver on the promise of clear drug targets for common diseases, the rapid gene-sequencing and publicly available data it spawned have enabled scientists to swiftly figure out the underlying cause of many rare diseases, NCAT’s Austin says. Two decades ago, scientists had teased out the molecular basis for fewer than 50 rare diseases, Austin says; today, they know the genetic underpinnings for roughly 4,500.

“That is a complete sea change,” Austin says. “Thirty years ago, when I was in training, I saw patients with these rare syndromes that were characterized in really arcane, clinical ways. We had no idea what the molecular basis was.”

That jackpot of genetic information has drawn new players to the rare disease space. Agios Pharmaceuticals, for example, saw exploring genetically defined rare metabolic diseases as a natural progression for its drug discovery platform, which was built to tackle cancer cell metabolism. At the same time, small patient populations mean Agios can develop its own pipeline of drugs without the infrastructure needed to commercialize treatments for more common diseases.

Investors like the strategy. In late 2011, Agios was able to raise $78 million to support its foray into rare diseases.

Big pharma’s interest in rare diseases took longer to foment. When Summit Corp. was spun off from England’s Oxford University in 2003 to develop drugs for Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a fast-moving muscle-wasting disease, it was clear that “big pharma just wouldn’t look at a disease like DMD,” says Andrew Mulvaney, a Summit cofounder and its director of business development. At the time, the biotech firms working on rare diseases were largely focused on lysosomal storage diseases, where the orphan drug model had been proven.

Today, a race for FDA approval between two firms—Prosensa and Sarepta Therapeutics—with drug candidates that treat a small slice of the DMD population is one of the closest-watched competitions in the biotech industry. And Summit, which has a drug with the potential to treat all children with DMD, suddenly finds itself being courted by big pharmaceutical companies, Mulvaney says.

Advertisement

The shifting interest comes as big pharma struggles to get new drugs across the finish line to offset revenue losses as, one after another, its blockbuster products lose patent protection. Suddenly, orphan products, including those for the rarest of the rare diseases, carry appeal.

In 2010, GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer became the most visible new players when they formed dedicated rare disease units. Others, such as Roche, have made a series of deals that collectively amount to a sizable rare disease portfolio.

But it was Sanofi’s purchase of Genzyme for $20 billion in 2011 that really put the spotlight on rare disease assets, according to Ritu Baral, a stock analyst at the investment firm Canaccord Genuity.

Venture capital firms have become equally enchanted with the rare disease space. Not only is significantly more venture capital being devoted to rare disease drugs today than in the past, “but I think there’s more venture capital money for orphan drugs than for any other type of drug, save oncology,” Baral says.

Some firms have even started funds specifically targeting rare diseases. Among the biggest moves was a partnership between Atlas Venture and Shire to make early-stage investments in rare disease opportunities. And just last month, New Enterprise Associates and Pfizer Venture Investments committed $16 million to Cydan, which will pluck rare disease projects from academia and start companies around the most promising ideas.

Figures for how much money has been poured into drugs for rare diseases are hard to come by. Many drug development pacts have been inked, but even venture capital firms working in the space can’t quantify the overall investment, a kind of hand waving that contributes to worries that interest in rare diseases is a fad.

One statistic everyone touts is growth in R&D projects. According to a recent report by the Analysis Group and Pharmaceutical Research & Manufacturers of America, a drug industry trade association, 1,795 projects in the clinical pipeline as of October 2011 had orphan designation. And between 2001 and 2010, the number of products with orphan designation grew 10% annually, despite a decline in the total number of drug candidates during that period.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter