Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Postdocs

Postdoc Pains And Gains

The experience may be getting more difficult, yet many chemists find it is both necessary and fulfilling

by Bethany Halford

May 16, 2013

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 91, Issue 20

The path for researchers who do two or more postdoctoral stints is littered with tough choices, reports Senior Editor Linda Wang from the ACS National Meeting in New Orleans

After five to seven years of working 70-plus hours per week and subsisting on a stipend that makes ramen noodles a staple of their diet, most chemistry graduate students see getting their Ph.D. as the light at the end of the tunnel. But they could be in for a rude shock when they begin looking for a job.

For Michael A. Tarselli, now a principal scientist at Woodbridge, Conn.-based Biomedisyn, the news that he would have to do postdoctoral research came just before he started graduate school, during a stint as an intern with a biotech company. “On the last day of my internship, my boss turned to me and said, ‘Listen, you might think getting a Ph.D. is going to get you a job back here. Well, it won’t. I won’t write you a letter of recommendation unless you do a postdoc too,’ ” he recalls.

So in 2009, after Tarselli finished his Ph.D., he spent the next year-and-a-half as a postdoc at Scripps Research Institute Florida. “I probably could have gotten a couple of jobs right out of my Ph.D.,” he says, “but I don’t think any of them would have met my career goal to be in pharmaceutical research.”

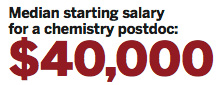

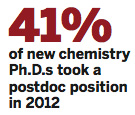

Many Ph.D. chemists find themselves in the same position as Tarselli. Some 41% of new Ph.D.s took a postdoc in 2012, according to the annual survey of new graduates in chemistry and related fields conducted by the American Chemical Society, which publishes C&EN. Since 2005, that percentage has generally hovered in the mid-40s. And according to the National Science Foundation, roughly 4,000 people, give or take a couple hundred, did a postdoc in chemistry each year from 2003 to 2010.

The ACS and NSF data seem to indicate that not much has changed for chemistry postdocs recently. However, observers have spotted some trends that are cause for concern.

For one, although there are no hard numbers to point to, some say people are spending more time in postdoctoral positions. In chemistry, one to two years used to be the norm, but that time frame may be creeping up. Some chemists tell C&EN that they are spending five or more years doing postdoctoral studies.

Salaries reflect another disturbing development: Postdoc chemists seem to be making less money than they used to. According to the ACS survey, in 2005 the median salary for postdocs was $36,000. In 2012 it was $40,000.

Although those numbers suggest that salaries are edging upward, they’re not when adjusted for inflation, says Gareth S. Edwards, senior research associate with the Department of Research & Member Insights at ACS. “Unfortunately, real dollar value—what that salary will buy you—is slowly decreasing, meaning that postdocs are earning less each year,” he says. From 2005 to 2012, salaries increased 11.1%, while the Consumer Price Index rose 16.1%.

Despite these worrisome trends, the current and recent postdocs who spoke with C&EN say the experience has largely been a positive one in which they’ve grown as scientists and broadened their professional horizons. Some see this phase as a last chance to pursue scientific research without being beholden to an employer or without the burden of running one’s own lab. Others regard it as yet another necessary step toward the career they want in chemistry research.

But after several years of doing research, do grad students really need to toil away as a postdoc? Although there are exceptions, the prevailing opinion is that doing a postdoc is a requirement for anyone who wants to be a professor running his or her own research group. “Even when I became a postdoc in the early 1970s, it was basically a necessity for getting an academic position,” says Paul L. Houston, a chemist and dean of the College of Sciences at Georgia Institute of Technology.

Industrial employers’ opinions are more variable, but they still give postdocs an edge. “It is a slight positive but by no means necessary for our jobs,” says Gary S. Calabrese, senior vice president at Corning. “If there is a particular technical need we have and someone has the right skills, it does not matter if it came through their Ph.D. or a postdoc. Having said this, of course those with postdoctoral experience are by definition broader and have a greater chance of being a technical match for us.”

Pat N. Confalone, vice president of DuPont Crop Protection, tells C&EN that although a postdoc isn’t a requirement to get a job at DuPont, it is a definite plus. “All things being equal, someone who has a postdoc is going to be more attractive to industry than someone without a postdoc,” he says.

“The majority of applicants that we see have postdoctoral experience,” adds Mark Namchuk, senior vice president of research for North America with Vertex Pharmaceuticals. “A postdoc is not essential, but it is becoming the norm. Aside from the additional experience, it often provides diversification of a scientist’s skill set.”

Unfortunately, the postdoctoral interval sometimes stretches beyond a reasonable time frame. The problem of extended postdocs has been around for a while in the biomedical sciences, says Stacy L. Gelhaus, a research assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh, who served as the National Postdoctoral Association’s chair of the board from 2008 to 2011. But the problem appears to be trickling into the physical sciences as well, she says, probably because of the dearth of tenure-track positions.

“A lot of places have a five-year time limit on postdocs,” Gelhaus says, “but not a cumulative time limit.” And that leads to another troublesome trend: multiple postdocs.

In its December 2012 report, “Advancing Graduate Education in the Chemical Sciences,” the ACS Presidential Commission on Graduate Education in the Chemical Sciences notes a “bulge” at the postdoc level because of the weak economy. “Particularly in more biological areas of chemistry, many current postdocs have previously been postdocs for one or even two appointments,” the report says. “For these individuals, the second, or later, postdoctoral appointment serves largely as a buffer zone in the ebb and flow of the job market; it is not a position that significantly improves one’s job chances.” It’s possible that this bulge isn’t apparent in ACS and NSF statistics because many chemists who are postdocs in biological areas of chemistry are classified as life scientists, whose numbers have grown dramatically in recent years.

“The challenge that postdocs are facing is probably the same that everyone is facing: a weak job market,” says Kelly O. Sullivan, who manages the Linus Pauling Distinguished Postdoctoral Fellowships at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and is the current president of Sigma Xi, the Scientific Research Society.

In terms of supply and demand for postdocs, the system is out of equilibrium on the supply side, and that state of affairs is driving postdoc salaries down, notes Paula E. Stephan, an economics professor at Georgia State University and author of “How Economics Shapes Science.” “There are many Ph.D.s being trained outside the U.S., who apply for postdoc positions in the U.S., so there’s practically an infinite supply of them,” she says.

Complaints of financial hardship are common among the chemistry postdocs who spoke with C&EN. “I wasn’t making much more than I was as a graduate student, and yet all of my student loans came due immediately,” Tarselli says. Postdocs also have to pay social security tax, whereas graduate students do not.

Samuel Lord, who has been a postdoc at the University of California, Berkeley, for two-and-a-half years, says that although he now earns a little more than he did as a graduate student, his cost of living in the expensive Bay Area takes a much bigger bite out of his paycheck. Also eating away at Lord’s earnings: Last year he started a family. “Having a kid on a postdoc salary is tough,” he says.

Because of the transient nature of the position, many postdocs end up putting off major life decisions, such as getting married and having children, until after they’ve finished their studies. “I have a twin sister, who I think is a good example of a normal person my age who is exactly like me but who isn’t a postdoc,” says Jessica Breen, a second-year postdoc at the University of Leeds, in England. “My sister is married. She’s got a mortgage and a house. She’s just had her first baby. I haven’t even thought about buying a house. I can’t even think about getting married because I don’t have money to do so.”

“I think postdocs are really underpaid,” says Stephan. Most universities use the National Institutes of Health’s Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award stipend as a benchmark of what their faculty should be paying postdocs. In 2012, the entry-level stipend for postdocs was $39,264.

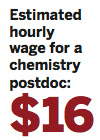

“NIH is recommending what I think are very low salaries,” Stephan says. She estimates that a postdoc working 53 hours per week earns an hourly wage of about $16. For a principal investigator to hire a postdoc costs relatively little, Stephan says, because the adviser doesn’t have to pay for tuition as they do for graduate students who serve as research assistants. Some argue that postdocs are getting training, and the way they pay for that training is to have a low salary, she notes. “I do think some postdocs get training, but there are a lot of postdocs out there who do very repetitive kinds of things and who are not receiving that much training.”

“There are many policy options that might improve the situation, but one that would certainly help would be to increase the salaries of postdocs, thereby lowering the incentives for faculty to employ postdocs as cheap labor and reflecting the expertise and skill they possess,” Stephan adds. She suggests raising postdoc stipends to around $50,000.

“I think there are situations where postdocs are basically being regarded as rather cheap employees to get research done and are not getting the benefit of career development they should be getting,” adds Georgia Tech’s Houston, who headed the working group on postdocs for the ACS commission on graduate education. Although some agencies, such as NIH and NSF, require postdoctoral advisers to have a mentoring plan, other agencies, such as the Department of Energy, are more focused on seeing deliverables from the projects they fund, Houston says.

The ACS presidential commission also expresses concern about postdocs’ incorporation into the university fabric. As neither students nor staff, their status and benefits can be somewhat murky, depending on the institution where they work.

Most academic postdocs are a result of an agreement between a principal investigator and a postdoc, with little involvement from the university. “Postdoctoral associates find themselves sometimes treated as employees, sometimes as students; often, they have the worst of both worlds,” notes the commission.

Patrick S. Barber, a postdoc in his second year at the University of Alabama, agrees with this assessment. Many postdocs, he says, simply don’t get the benefits that permanent employees take for granted. “Having universities provide basic documented benefits in line with those of regular university employees, such as paid vacation and maternity leave, would relieve some of the stress associated with postdoc positions,” he says.

To Take, Or Not To Take … Another Postdoc

\

“Postdocs are starting to become a substitute for real jobs.”—William F. Banholzer, executive vice president and chief technology officer of Dow Chemical

The mismatch between the number of available jobs in the chemical sciences and an oversupply of Ph.D. graduates seems to be driving up the number of years people are spending as postdocs. In a video produced by C&EN, postdocs and employers discuss the potential consequences of taking on serial postdoctoral assignments. Watch it at http://cenm.ag/postdv.

As if the low salary didn’t make saving for the future tough enough, postdocs who are classified as trainees or who are on fellowships can’t have 401(k) retirement plans, notes Pittsburgh’s Gelhaus. “If you’re postdoc-ing for a year or two, it’s not such a big deal,” she says. “But now that people are doing postdocs for five years, it’s become more of an issue.”

“Prepare to sacrifice financially and move temporarily for your postdoc,” advises Xin Chen, a chemistry professor at Boston University who finished his second postdoc in 2011. “It’s a continuation of your intellectual investment in your future.”

Despite their complaints, the current and recent postdocs who spoke with C&EN say they have enjoyed the experience. “A postdoc is a unique opportunity to fine-tune the skill set you learned during your Ph.D.,” says Steven Hira, a postdoc in his second year at Georgia Tech. “It’s a tremendous time of learning and growing and an important component of intellectual development.”

Advertisement

“There is a lot of flexibility in the postdoc work schedule,” UC Berkeley’s Lord points out—a fact that made having a child while he was a postdoc somewhat easier. “I work a lot, but my hours are flexible.”

Others see the transitory nature as a positive aspect of the position. Matthew Remy, who just completed a two-year postdoc at Pennsylvania State University, says, “That limited time at the outset gave me the freedom to be open to any possibility for a postdoc. My wife and I thought, ‘It’s only going to be two years. We can go where we want and experience something new.’ ”

“To the extent that a Ph.D. is training you to plan and conduct original research, a postdoc offers you the chance to put that training into practice with the least amount of administrative burden,” says Christopher J. Cramer, a chemistry professor at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities.

He suggests graduate students start looking for their postdoc about a year before they intend to graduate. The ideal postdoc experience expands a chemist’s skill set and offers a high degree of intellectual freedom. Also, Cramer recommends that students looking for a postdoctoral mentor should pay attention to the rumor mill and avoid applying to people with a reputation for being difficult.

A postdoc, Cramer says, is the final opportunity a scientist has to be intensely focused solely on doing research. “People should try to take advantage of that last chance and appreciate how much fun it can be to be a pure scholar,” he says. “But I certainly also understand that anxiety of not knowing what comes next.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter