Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

California Begins Carbon Controls

Cap and trade to be modest yet critical element in new statewide greenhouse gas reduction program

by Jeff Johnson

February 18, 2013

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 91, Issue 7

In January, California entered the new world of carbon trading with the official kickoff of a statewide program to begin trading greenhouse gas emissions. For the state, it has been a long journey and one that is far from over.

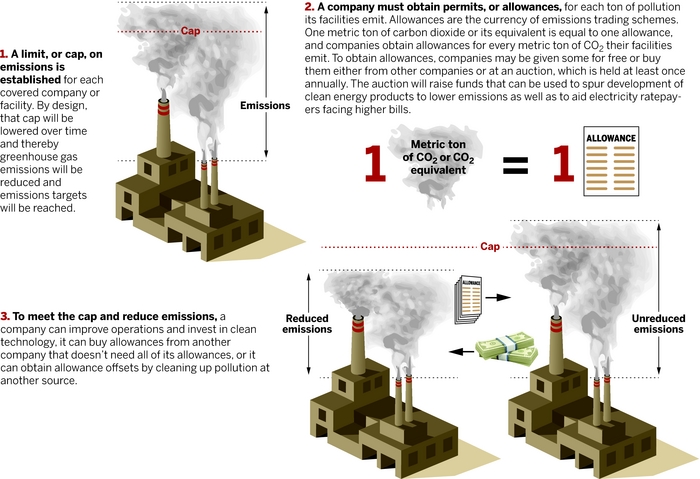

The market-based carbon trading scheme is a key component in a broad state plan to address climate change and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The scheme calls for the state to set a declining cap on carbon emissions and require participating entities to obtain allowances—either for free from the state or by purchasing them at auctions or from other companies—for every metric ton of CO2 or CO2 equivalent they emit. Because the program is just getting started, most allowances will be free.

The goal of California’s broad climate change plan is to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 2020 to the levels generated in the state in 1990. When fully implemented, the cap-and-trade program will cover about 85% of the state’s greenhouse gas emissions and will reduce CO2 emissions from electricity generators, refineries, and chemical companies and other businesses, as well as vehicles, that operate in the state.

COVER STORY

California Begins Carbon Controls

The cap-and-trade program will cover some 360 companies, collectively running about 600 California facilities that have emissions above a threshold of 25,000 metric tons of CO2 or CO2-equivalent emissions annually.

Dave Clegern, a spokesman for the California Air Resources Board (CARB), which runs the program, explains how it works: Covered companies must obtain enough allowances to match their emissions. They also face a declining emissions cap, which is set by CARB on the basis of past emissions and improvements the facility can make to reduce emissions. The cap stays flat in the first few years and then declines by 1 to 3% a year, depending on the economic sector. To meet the cap, greenhouse gas generators can cut emissions, buy allowances, or get a small number of offsets, in which they reduce emissions in other economic sectors and credit those gains to their facility emissions.

The program began last month with electricity generators, large industrial emitters, and utilities; in 2015 distributors of transportation fuels, natural gas, and other fuels will be rolled into the program. Under the law that created the CO2 cap-and-trade reduction scheme, the program is supposed to end by 2020, which is quite likely if it fails, less so if it succeeds.

Success for the carbon trading program would mean meeting its goal within the overarching California plan to cut by 2020 greenhouse gas emissions by 15% compared with the emissions level resulting from a business-as-usual scenario in which no state programs reduced emissions. The lion’s share of California’s greenhouse gas inventory is CO2. Other greenhouse gases being emitted include methane, nitrous oxide, sulfur hexafluoride, nitrogen trifluoride, hydrofluorocarbons, and perfluorocarbons. Under the trading system, the emissions of these other greenhouse gases are converted to CO2-equivalent emissions.

Some 427 million metric tons of CO2 or CO2 equivalents was emitted in 1990, according to state figures, and 507 million metric tons would be emitted in 2020 without pollution control efforts. This means that 80 million metric tons of CO2 must be eliminated to meet the state-set broad goal. The cap-and-trade scheme will be responsible for 18 million metric tons of that reduction target.

Last November, the state began laying the groundwork for implementation of the trading scheme when it held its first allowance auction. California sets a minimum on the allowance prices, which was $10 per ton for the first auction. The minimum bid will increase with time.

In this first auction, California sold allowances to cover 23 million tons of CO2 or CO2-equivalent emissions, a small fraction of the overall level of greenhouse gases being emitted in the state. Each allowance sold for $10.09, generating $233 million for the state. The auctions will be held quarterly with the next one set for later this month.

The auction was intended to get things started and to generate interest as well as funds to begin the cap-and-trade program, Clegern explains. Auction revenues will go toward aid for electricity ratepayers who will likely face higher bills and toward supporting development of cleantech.

Nearly all allowances will be given away free in the early years, providing time for companies to figure out how to make reductions to comply with the declining cap before it hits with full force, Clegern says.

Although cap and trade is getting a lot of attention, it is just part of a “climate-change package,” says Kevin Kennedy, director of World Resources Institute’s Climate Initiative. WRI is a Washington, D.C.-based think tank. Until February 2011, Kennedy was director of CARB’s Office of Climate Change.

The overall California climate-change plan, including the cap-and-trade program, was established by a controversial law, called Assembly Bill 32, which Republican Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger signed into law in 2006.

In the legislative debate over the law, Kennedy says, the fight boiled down to conflicts between Republicans who worried the package of limits and incentives would harm industry and Democrats who wanted a straight-ahead, trimmed-down regulation to cut greenhouse gas emissions. The resultant package includes a combination of limits and incentives to encourage production of low-carbon fuels, noncarbon renewable energy, energy-efficient technologies, and other carbon reductions.

The carbon trading program was intended to be a backup, Kennedy says. The law punted to CARB the responsibility to develop and implement the program over the years. The program is a work in progress.

Assembly Bill 32 had strong support from several national and state environmental groups, particularly the Environmental Defense Fund, which has a history of backing market-based environmental initiatives. Timothy O’Connor is director of EDF’s California Climate Initiative and a former California regional air inspector.

To him, cap and trade is the “grease on a bicycle chain,” needed to focus the overall state emissions reduction effort and make sure it moves ahead smoothly and to step in if other elements fail to keep the state on track to get the needed reductions by 2020.

Industry has been less enthusiastic about the overall greenhouse gas reduction effort or the carbon trading scheme. But companies and trade associations C&EN contacted had little to say about the details of the effort in general or the cap-and-trade program specifically.

However, the California Chamber of Commerce is suing the state, seeking to invalidate the cap-and-trade auction. The chamber says it does not challenge Assembly Bill 32 or climate-change science, but it does challenge CARB’s authority under state law to keep and sell emissions allowances, a key to the trading scheme.

The chamber says the auction is also not needed to meet the 2020 reduction target, a perspective echoed by others in the regulated community.

California CO2 emissions have already declined. Over the past few years, projections for the business-as-usual CO2 or CO2-equivalent emissions in 2020 have fallen, based mostly on the stalled economy and the other state CO2 reduction programs that were part of Assembly Bill 32. For example, just a year ago, state projections predicted nearly 600 million tons of annual emissions by 2020. Recently, that number has fallen to 507 million tons. This drop in projected emissions happened without the cap-and-trade program, industry groups point out.

About half the decline was attributed to an economic downturn in California, but 40 million tons of reduced CO2 or CO2-equivalent emissions were attributed to other state programs, particularly efforts to increase vehicle efficiency and to require electric utilities to buy noncarbon, renewable energy. The state’s renewable energy standard requires one-third of the state’s electricity to be generated from noncarbon sources, such as solar, wind, and biofuels, by 2020. It is the toughest standard in the nation, and it is on track to succeed, O’Connor says.

However, O’Connor and CARB officials say the economy is now improving, and as emissions grow, the cap-and-trade scheme will be needed to keep the state greenhouse gas reduction effort moving ahead.

The oil industry has been the most aggressive opponent of, and one of the most affected by, Assembly Bill 32. Of the 15 top CO2-emitting facilities, 10 are refineries. In 2010, the industry geared up for a major attack—pushing for a state electoral proposition to block the law’s implementation. Three oil companies led the way—Valero and Tesoro, with headquarters in Texas but refineries in California, and the owners of Koch Industries, a Kansas-based oil conglomerate. They raised more than $7 million in a very visible election campaign.

The fight was nasty, with then-Gov. Schwarzenegger accusing the oil industry of “self-serving greed.” He warned that the proposition would kill the state’s growing clean technology industry, which he strongly advocated for and called the fastest-growing sector of the state’s economy. Portions of the allowance auction receipts are to go to develop clean technologies, and the overall program’s emissions reduction goals are expected to fuel development of new products sold by the state’s cleantech industries in the global marketplace.

The oil industry proposition was defeated 61% to 39%, a clear signal to other opponents that the law has deep public support and they’d better get used to it.

The trading program is particularly complicated for the electricity sector, which generates slightly more than one-fifth of the state’s greenhouse gas emissions. About half of these emissions are generated by in-state electricity providers. The other half comes from facilities outside the state that sell power to California utilities. In-state generators are directly covered; utilities that buy out-of-state electricity must have sufficient allowances to cover the emissions associated with the electricity they buy. Electricity generators get no free allowances.

For chemical companies, oil refineries, and other industrial emitters, 90% of needed allowances are free for the first two years, Clegern notes. The cap will then decline and the share of free allowances will also decline, reaching about 50% of overall allowances by 2020. The cap will be based on a company-sector benchmark or average emissions level and backed up by an “army of third-party verifiers” who visit plants, measure emissions, and certify that improvements companies say they have made are real, Clegern says.

CARB officials note that chemical companies and others with high energy demands and competitive global markets may need extra help, particularly in early years. The fear is that the state program may lead to higher operating costs and expensive products that aren’t competitive with products made by out-of-state companies that do not face greenhouse gas restrictions. The free allowances are intended to address that fear, CARB says.

O’Connor says the free allowances will also provide breathing room while companies improve operations or install higher efficiency equipment. But free allowances also have the potential to flood the carbon market and allow companies to effectively avoid reducing greenhouse gas emissions, which appears to be happening in the European Union, which has the largest carbon trading program (see page 16).

“Industry should have 100% free allowances,” says Shelly Sullivan, AB 32 Implementation Group’s executive director. AB 32 Implementation Group is an organization formed when Assembly Bill 32 became law. Its members are a mix of companies and trade associations, including the American Chemistry Council, a national chemical trade association. Sullivan says the payments for allowances are a “tax on doing business in California.”

“We can make the reductions spelled out in the law without being in the carbon trading program,” Sullivan stresses.

“CARB is well aware of their views,” Clegern responds, “but that is not the way it is going to work.”

In 2015, the cap-and-trade program will be expanded to include transportation fuels and natural gas carbon emissions. The law will cap and lower emissions from this critical sector by requiring fuel distributors to obtain allowances.

Under the law, the state’s overall greenhouse gas emissions reduction program—including the cap-and-trade scheme—is targeted to end in 2020. But the assumption in 2006 was that a national carbon reduction bill was on the horizon and it would cover emissions reductions beyond 2020.

Advertisement

The U.S. Congress balked, and that did not happen.

The 2020 limit concerns O’Connor. “In the last years of the program, there is not going to be much incentive for companies to make large investments, and that is when the biggest reductions are required,” he says.

However, Clegern adds, “Our ultimate hope is that the state will be consumed by a federal cap-and-trade program, but barring that we will get something else in the hopper. We will probably start dealing with what that may be around 2017 or 2018.”

Meanwhile, Clegern says, the state will tweak the program, try new science, and reexamine the economic conditions as they set down plan details. “We are looking at a longer time horizon and at reducing emissions all the way out to 2050.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter