Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Analytical Chemistry

Bomb Blasts Alter Brain Lipids

Neurochemistry: Using mass spectrometry imaging, researchers detect higher levels of a certain lipid in the brains of mice exposed to a mild explosion

by Erika Gebel

January 18, 2013

About 320,000 soldiers returning from the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have struggled with neurological problems associated with traumatic brain injury, according to the Rand Corporation. Some veterans experience symptoms, such as memory loss and anxiety, without physical signs of brain injury. Now researchers report a possible chemical signature: Levels of a certain lipid spike in the brains of mice exposed to mild explosions (ACS Chem. Neurosci., DOI: 10.1021/cn300216h). This lipid could serve as a biomarker for people who are at risk of developing neurological disorders after a blast, the scientists say.

When a bomb explodes, a shockwave of high air pressure spreads out from the detonation site and “compresses all the soft tissues in the body,” says Amina S. Woods of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Through magnetic resonance imaging and X-ray computed tomography scans, doctors can spot physical signs of brain damage caused by large explosions. But mild blasts don’t always produce noticeable injuries.

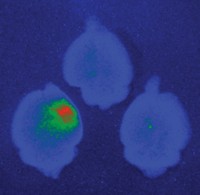

To understand the effects of mild blasts on the brain, Woods and her team sedated groups of mice and held them at either 4 or 7 meters from a small TNT bomb. After detonating the bomb, the researchers examined the animals’ brains and found no apparent physical injury.

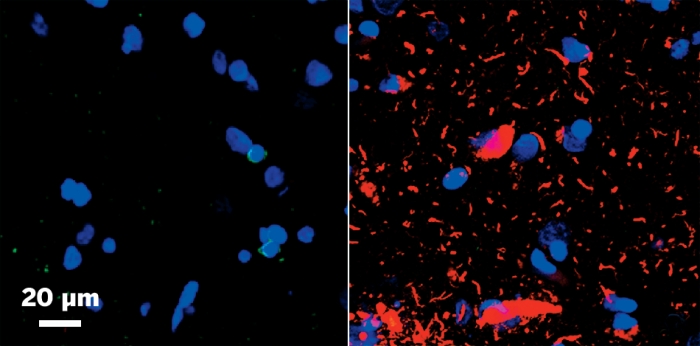

The team then scanned slices of the animals’ brains two, 24, and 72 hours after the blast using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry imaging. The technique detects the types of proteins and lipids at each point in a tissue slice, allowing the scientists to produce a chemical map of the animals’ brains.

Compared to the brains of mice not exposed to a blast, brains of mice after the explosion had higher levels of a lipid called ganglioside GM2, with the largest concentrations in the hippocampus, thalamus, and hypothalamus. Gangliosides are molecules that contain sugars and lipids. Mice that sat 4 meters from the blast had the greatest concentrations of ganglioside GM2. The lipid levels were high in scans at two and 24 hours after the explosion, but went back to preblast levels by 72 hours.

When the scientists scanned the literature for references to ganglioside GM2 and neurological disorders, they found that people with Tay-Sachs, an inherited neurodegenerative disease, often have high levels of the lipid in their brains. When Woods looked at the symptoms of late-onset Tay Sachs, she was surprised: “They mirrored a lot of the signs and symptoms in soldiers exposed to blasts.” She thinks researchers should next try to connect high levels of the lipid and symptoms of traumatic brain injuries.

Jeffrey Agar of Brandeis University called the post-blast ganglioside spike “pretty striking,” especially considering the mice weren’t exposed to a large explosion. Because the team observed the lipid increase in areas connected to the brain’s circulatory system, Agar wonders if they could detect the lipid in spinal fluid or even blood. If so, the ganglioside could serve a biomarker for traumatic brain injury.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter