Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Analytical Chemistry

Assay Detects Minuscule Amounts Of Gluten In Food

Analytical Chemistry: A new method based on small nucleic acid receptors senses gluten levels lower than 1 ppm

by Louisa Dalton

February 20, 2014

A food that’s labeled “gluten-free” isn’t necessarily free of gluten: It can contain up to 20 ppm of the protein. Yet for some people with celiac disease, even minute amounts of gluten will trigger intestinal pain and other symptoms. To improve upon current detection methods, researchers in Spain have created a new type of gluten assay that senses gluten concentrations as low as 0.5 ppm (Anal. Chem. 2014, DOI: 10.1021/ac404151n).

Gluten is a complex mixture of proteins found in some grains, including wheat, barley, and rye. Partially digested peptides from gluten spur a celiac patient’s immune cells to attack the lining of the small intestine, causing intense pain, growth delays, infertility, or other symptoms. The only remedy for celiac disease, which affects about 1% of people in the U.S. and Europe, is to stick to a gluten-free diet.

In the U.S. and much of Europe, a gluten-free label indicates that a product holds less than 20 ppm gluten, close to the limit of detection of traditional antibody-based tests. María Jesús Lobo-Castañón of the University of Oviedo, in Spain, and her colleagues work on biosensors and wanted to develop a test for allergens. After learning that a colleague was so gluten-sensitive that even products labeled gluten-free could trigger his symptoms, they decided to devise a sensitive test for gluten.

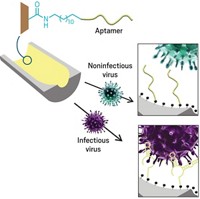

Typical gluten detection tests depend on antibodies that specifically bind to gluten or portions of it. But small nucleic acid receptors, or aptamers, are easier to make and tweak, more stable, and less expensive than antibodies, Lobo-Castañón says.

Lobo-Castañón’s group first chose a target from gluten’s complex protein mixture. They picked one of the most immunotoxic constituents of gluten: a 33-amino-acid stretch from the protein gliadin. To identify an aptamer against the gliadin peptide, the Spanish group began with a very large library of random DNA sequences, each 80 nucleotides long. The researchers identified sequences that bound to the gliadin fragment, separated them, and amplified them. They repeated the process 10 times to find the aptamer with the greatest affinity for their gliadin fragment.

Aptamer in hand, the scientists put together a competitive gluten detection assay. They attached the gliadin peptide to magnetic beads. Then they mixed a food sample with the beads and added a small amount of aptamer. Any gluten in the food competes with the gliadin on the beads to bind to the aptamer, which allows the researchers to detect very low levels of gluten present in the food. By measuring the percentage of aptamer bound to gliadin, the researchers could calculate how much gluten was in the food, at levels as low as 0.5 ppm.

The researchers found that their aptamer bound tightly to wheat, barley, and rye flours, but not at all to corn, rice, and soy flours, which are naturally gluten-free. Using the technique, they also tested soy baby formula and a cake mix with known gluten concentrations. Their test confirmed that no gluten was in the cake mix and that the baby formula had 16 ppm gluten.

José Manuel Pingarrón of Complutense University of Madrid sees promise in the new method. It shows more reliable results “at low concentrations, where other methods fail,” he says. More sensitive gluten testing would be a boon for those people affected by even a smidgen of the protein.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter