Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Analytical Chemistry

Mass Spec Method Quickly And Accurately Identifies Pathogens

Medical Diagnostics: The technique can distinguish between species, and even strains, of bacteria and fungi

by Erika Gebel Berg

June 12, 2014

A mass-spectrometry-based method can rapidly identify the species and strain of bacteria and fungi responsible for infections (Anal. Chem. 2014, DOI: 10.1021/ac501075f). Doctors could use such a technique to find the microbial culprits behind life-threatening infections in patients, allowing them to save precious time and pick the most effective antibiotics for the specific species or strain, the researchers say.

The standard way to identify a microorganism in the clinic is to grow cultures in the laboratory and look for characteristic physical properties, a process that can take days. In recent years, culture-free methods have emerged that identify microbes based on their characteristic 16S ribosomal RNA sequences. However, these approaches often require extensive sample preparation and still sometimes fail to make an unequivocal designation, limiting their usefulness.

Mass spectrometry could be a quick alternative to gene sequencing, says Zoltan Takats of the Imperial College London. He and his colleagues envisioned using the technique to obtain profiles of the lipids in different microbes and then using those molecular signatures to identify species. Such profiles may also provide additional information, such as the capacity of a microorganism to cause disease, he says.

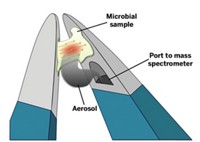

To test their idea, Takats’s team used a method called rapid evaporative ionization mass spectrometry (REIMS) to analyze 28 species of bacteria grown under a variety of conditions. They picked up colonies they wanted to analyze with a device that looks like a pair of forceps. The tip of the forceps is wired: When the researchers flip a switch, current pulses through the device, generating a cloud of mostly lipids from the selected colony. The airborne lipids are then drawn into a fluid line embedded in the body of the forceps, directing the molecules to the spectrometer for detection. Takats says the forceps could be adapted to gather samples taken from a patient’s mucosal membranes.

A computer program analyzed the spectra and compared the colonies’ lipid profiles, allowing Takats’s team to successfully distinguish all 28 species of bacteria and five species of Candida fungi. They could make the identifications regardless of growth conditions and often at greater than 95% accuracy. The identification process, from picking the colony to running the program, took as little as three to five seconds. To see if they could identify different strains of the same types of bacteria, the researchers analyzed seven strains of Escherichia coli and found they could distinguish them with around 90% accuracy.

The technique’s ability to distinguish microorganisms based on their lipid profiles is surprising and exciting, says Charles Y. Chiu of the University of California, San Francisco. However, he points out that the study was done with pure colonies, which have a high concentration of organisms. “In clinical samples, it’s more of a needle and a haystack,” Chiu says.

Chiu also wonders if the method will be able to distinguish between dangerous and harmless versions of the same microorganism. Takats says that is his goal, and he is currently working to discriminate between pathogenic and innocuous strains of Clostridium difficile.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter