Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

Microneedles For Painless Delivery Of Vaccines And Nanomedicines

ACS Meeting News: Within minutes, researchers fabricate tiny biodegradable hypodermics with encapsulated enzymes and nanoparticles

by Lauren K. Wolf

August 13, 2014

For safer, cheaper, and painless delivery of vaccines and large, protein-based drugs, scientists want to create microarrays of needles short enough to avoid nerve cells but long enough to pierce the outer, protective layers of a person’s skin. Research teams have developed these so-called microneedles, but fabricating the tiny hypodermics typically requires numerous steps and takes hours to days.

At the American Chemical Society national meeting in San Francisco this week, graduate student Katherine A. Moga described a method for mass-producing microneedle arrays within minutes. Moga and other members of Joseph M. DeSimone’s research team at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, recently used the technique to make needles loaded with an active enzyme or with nanoparticles.

“No one likes getting a shot, not even me,” Moga said during a session in the Division of Colloid & Surface Chemistry. But vaccines and proteinaceous drugs can’t be taken orally because the digestive system breaks them down, she explained.

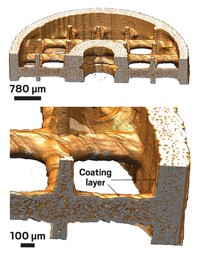

Last year, DeSimone’s team adapted a process dubbed PRINT (Particle Replication In Non-wetting Templates) to manufacture microneedles made of polyvinylpyrrolidone, a biodegradable polymer approved by the Food & Drug Administration for use in drug formulations (Adv. Mater. 2013, DOI: 10.1002/adma.201300526). Making microneedles with this patented technique is like filling “really small ice cube trays,” Moga told C&EN.

The researchers first make a perfluoropolyether mold covered with pyramid-shaped holes. Then they fill this “ice cube tray” with a mixture of polyvinylpyrrolidone and either enzymes or nanoparticles. Finally, they add to the needles a backing layer made of water-soluble polymer and then peel the whole assembly out of the mold.

When gently pressed into excised human skin or live mouse skin, the microneedle patch punctures the surface and then releases its cargo as it degrades, Moga said. The backing layer dissolves after exposure to a few drops of water.

The team demonstrated that when encapsulated in the needles, the model enzyme butyrylcholinesterase remained almost 100% active. Similarly, polymer nanoparticles stayed intact during the microneedle fabrication process, which bodes well for the tiny hypodermics one day being used to deliver vaccines and nanomedicines.

“This work makes an important advance in the field by demonstrating the ability to fabricate microneedles using a manufacturing technology that lends itself to low-cost mass production,” said Mark R. Prausnitz, a microneedle expert at Georgia Institute of Technology.

According to Paula T. Hammond, a chemical engineer at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, “The versatility of the method is exciting,” because it should enable scientists to tune the release of a broad range of cargo over time.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter