Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

Charged Polymers Package Proteins

Drug Delivery: Researchers use oppositely charged polypeptides to create a protective sphere around proteins

by Sarah Webb

October 20, 2014

Though protein drugs are becoming increasingly important therapeutics, there are still challenges to delivering them within the body. Proteases can chop up the molecules as they travel within the bloodstream, making it difficult for the proteins to reach tissues and cells at the proper dosages. Now researchers report a new way to encapsulate proteins, using oppositely charged polymers that encase them in a protective bubble (ACS Macro Lett. 2014, DOI: 10.1021/mz500529v).

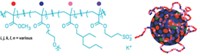

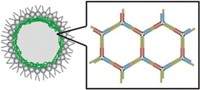

Lipid micelles and polymers such as polyethylene glycol are among the many options for encapsulating proteins. To develop another, easy-to-control packaging method, Matthew Tirrell of the University of Chicago and his colleagues turned to complex coacervation—the process of forming liquid droplets through the assembly of positively and negatively charged polymers in solution. They envisioned that polypeptides of positively charged L-lysine (PLys) and negatively charged D/L glutamic acid (PGlu) would form dense spheres, trapping their proteins of choice. PLys and PGlu had already been used to coat biomaterials, and Tirrell and his team had previously shown that these polymers form coacervate structures in solution.

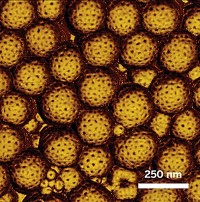

To implement their protein encapsulation idea, the researchers put bovine serum albumin (BSA) in solution and then added PLys followed by an equal amount of PGlu. When the researchers used a 20:1 ratio of polypeptide to protein, they formed 4-µm-wide droplets. Using a fluorescent tag on BSA, they verified that the protein was encapsulated within the spheres. Biophysical tests also showed that BSA maintains its highly helical structure within the coacervates. Droplets remain stable at neutral pH but begin to disintegrate below pH 5, which should allow them to remain intact within the bloodstream but selectively release their cargo when they hit low-pH regions inside cells. Coacervates made with PLys and PGlu were not cytotoxic, though PLys on its own can be mildly toxic to cells, a possible concern once the coacervates disintegrate.

In further work, Tirrell and his team are looking at better ways to control the size and aggregation of the droplets. For example, they might adjust the polymer ratios to give the droplets a slight charge, or create uniform droplets by squirting them through a microfluidic nozzle.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter