Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Chemical Communication

Cheerios-Fed Fungi Yield Biofilm Blockers

Natural Products: Soil fungi dine on breakfast cereal, then construct metabolites that block yeast biofilms

by Louisa Dalton

October 16, 2014

Convincing fungi to trot out their whole gamut of metabolites is a persistent challenge of natural product chemists. These researchers hunt for novel compounds with possible therapeutic value within the chemical soup that the fungi produce. Now, one team has hit upon a curiously effective and consistent way to prod the organisms to start synthesizing: Cheerios inside bags. Scientists grew a soil fungus for four weeks in a bag full of Cheerios and discovered a new compound that can block biofilm formation by an infectious yeast (J. Nat. Prod. 2014, DOI: 10.1021/np500531j).

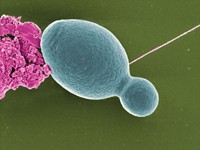

A yeast infection brought on by Candida albicans will vex, at one time or another, about 75% of healthy women. In immunocompromised patients, the ubiquitous fungus can be intractable. Once it gets a foothold, C. albicans often puts up a biofilm, a shield of polymeric slime that repels immune system attacks and antifungal drugs. A drug that could block biofilm formation would prevent recalcitrant infections and make antifungal treatments more effective, says Robert H. Cichewicz, a natural products chemist at the University of Oklahoma.

His lab has been searching through fungi metabolites for novel compounds with antibiofilm properties. But cultivating fungi using standard laboratory protocols—Erlenmeyer flasks filled with broth—often leads to the same common mycotoxins.

Cichewicz was convinced the fungi could make different, novel compounds if he could find the proper growing conditions. So in 2007, Cichewicz started hunting Walmart aisles and his kitchen cabinets for alternative fungus fodder. The chemist hit the jackpot with a box of stale Cheerios.

“Pretty soon we were getting rich, luxuriant lawns on top of the Cheerios,” Cichewicz says. The fungi grew in all the crevices, leaving behind “fuzzy doughnut shells where the Cheerio used to be.” The lawns were colorful, indicating large numbers of fungal metabolites. Also, Cheerios overcame a common problem in growing fungi. Standard growth media varies in composition from batch to batch. These small variations can alter fungi growth, meaning researchers can’t consistently produce the same set of metabolites with each experiment. However, one Cheerio is the same as another, box to box, batch to batch, today or years from now.

The idea to put the Cheerios in a bag instead of a flask came in 2011, when Cichewicz stumbled upon a how-to blog for growing psychedelic mushrooms. Those growers use big, breathable plastic bags called mushroom bags. One 50-cent bag, Cichewicz calculated, would provide the same growing surface area as 18 Erlenmeyer flasks. That would cut back on graduate student hours spent washing glassware, he thought. When his team took one promising fungus, Bionectria ochroleuca, and compared its growth on Cheerios in flasks versus in mushroom bags, they found that the species produced a similar metabolite profile under both conditions.

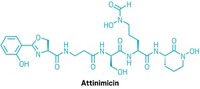

The fungus made three new bioactive compounds the scientists call bionectriols. The compounds were potent in preventing both growth and biofilm formation of C. albicans. Also, the bionectriols enhanced the potency of amphotericin B, one of physicians’ last lines of defense for treating fungal infections.

Nicholas H. Oberlies of the University of North Carolina, Greensboro, agrees that the antibiofilm properties of the bionectriols are intriguing. But he also is impressed with Cichewicz’s Cheerios-based cultivation method. “The clever thing is that he got General Mills to take the variability out for him,” Oberlies says.

Cichewicz continues to extol the benefits of Cheerios for growing fungi. “There is no other cereal that even comes close,” he says. “And believe me, I’ve tested the whole cereal aisle now.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter