Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

Hydrogel Electronics

Soft Materials: Researchers hack implant and wearable device surface chemistry to entice better bonding with their flexible polymer support

by Matt Davenport

December 21, 2015

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 93, Issue 49

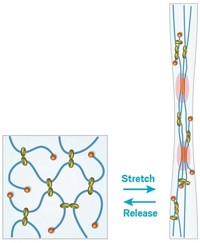

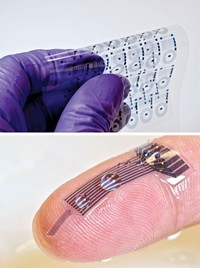

Hydrogels are a lot like people: squishy and made mostly of water. That makes these soft materials attractive supports for biomedical devices, such as implantable sensors and diagnostic wound dressings, because their properties are similar to biological tissue. But hydrogels are difficult to interface with electronics that are rigid and easily damaged by water, says Xuanhe Zhao of Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Zhao and his team overcame this problem by developing a way to make hydrogels cling to electronic components while staying flexible and stretchy like tissue (Adv. Mater. 2015, DOI: 10.1002/adma.201504152). To improve the bond between electronics and hydrogels, the researchers first encased active electronic components, such as light-emitting diodes, in a silicone elastomer. They then fixed the silicone to a thin piece of glass and functionalized the glass surface with 3-(trimethoxysilyl)propyl methacrylate. The methacrylate-functionalized surface bound with polyacrylamide in the team’s hydrogel. The covalent bonds hold the electronic hydrogel device together, even as it bends and stretches, Zhao says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter