Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Land Animals Could Pick Up Methylmercury From The Sea

Environment: Analysis of Arctic lichens shows that the ocean may be an important source of the toxic compound worldwide

by Janet Pelley

April 27, 2015

People and animals in the Arctic have some of the highest levels of methylmercury in their tissues in the world. Environmental scientists have long known that the neurotoxic compound readily moves through aquatic food chains, accumulating in apex predators. But now researchers report for the first time that the ocean might pump methylmercury into terrestrial food webs via lichens growing near Arctic coastlines (Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.5b00347).

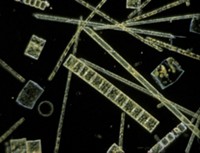

Mercury emitted into the atmosphere from industrial sources such as coal plants is mostly inorganic and not as harmful as methylmercury, which is an organic form. However, when inorganic mercury is deposited into lakes and oceans, aquatic bacteria transform it into methylmercury.

A 2012 Canadian government report showed that not much was known about how mercury moves through the terrestrial food web, says Kyra St. Pierre, an environmental science graduate student at the University of Alberta. Earlier studies that tested lichens growing on Arctic coasts found high levels of total mercury but didn’t determine if any was methylmercury. Because lichens make up 77% of the wintertime diet of caribou, a popular source of meat for aboriginal people, St. Pierre and her team wanted to know whether the mercury was coming from the ocean and how much was methylmercury.

They picked two islands in the Arctic Ocean as their testing sites. Devon Island is locked in ice for most of the year, which eliminates any possible mercury inputs from the ocean. But neighboring Bathurst Island is next to several areas of year-round open water. The team sampled lichens and soil along a path running from the coast to 24 km inland on each island.

The researchers used inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry to measure levels of total mercury, methylmercury, and elements associated with the marine environment, such as sodium. The scientists found a median concentration of 4.27 ppb methylmercury in the lichens—about 100 times as much as in underlying soil. On ice-bound Devon Island, the levels of mercury were the same no matter where the samples were collected. But on Bathurst Island, lichens within 10 km of the coast had 10 times as much methylmercury and sodium as the lichens growing inland.

“The results show that the closer you get to the open sea, the higher the methylmercury and sodium levels you have,” says Lars-Eric Heimbürger, a chemical oceanographer at the University of Bremen, in Germany. “That’s evidence that the mercury in coastal lichens must be coming out of the ocean.” The study is important because it confirms previous findings showing methylmercury can escape from the ocean, and the data link the oceanic mercury to caribou, a local food source in the Arctic, he says.

Elsie M. Sunderland, a marine chemist at Harvard University, says the study challenges the common dogma that terrestrial food webs are usually not contaminated with methylmercury.

This is probably not an Arctic-only phenomenon, St. Pierre says: The transfer of methylmercury from marine waters into terrestrial food webs is likely occurring on coasts worldwide.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter