Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Heroin Analog May Form Carcinogen In Drinking Water

Environmental Chemistry: Methadone in surface water reacts with drinking water disinfectants to form potent carcinogen

by Janet Pelley

May 29, 2015

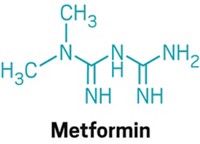

Drinking water disinfectants such as chlorine have put a virtual end to waterborne disease in developed nations but have spawned a new problem: They produce carcinogenic disinfection by-products. Health regulators would like to know more about the precursors of these by-products, particularly of one of the most potent ones studied to date, N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), in order to reduce their presence in drinking water. For the first time, scientists report that the painkiller and heroin analog methadone—ubiquitous in river and lake water from wastewater discharge—could be an important precursor of NDMA found in drinking water (Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2015, DOI: 10.1021/acs.estlett.5b00096).

In the mid-1970s, scientists discovered that chlorine disinfectant, a powerful oxidant, converts organic compounds from decaying plant matter in surface waters into carcinogenic trihalomethanes. To avoid this problem, many municipalities switched to using chloramines to disinfect drinking water because they produce up to 90% less trihalomethanes, says Susan D. Richardson, an environmental analytical chemist at the University of South Carolina who was not involved in the work. But chloramines react with largely unknown organic nitrogen precursors to form NDMA. In animal studies, NDMA causes liver, kidney, and respiratory cancers. Environmental Protection Agency guidelines say NDMA should not exceed 0.7 ng/L in drinking water, but “a significant portion of the U.S. population is exposed to NDMA at concentrations above this level,” Richardson says.

Scientists know that treated sewage effluent is a potent source of NDMA building blocks, “but identifying them is difficult because there are hundreds of thousands of compounds in wastewater,” says David Hanigan, an environmental engineering graduate student at Arizona State University and lead author of the new study. Earlier studies picked a handful of pharmaceuticals and reacted them with chloramines to see if they formed NDMA. These “shotgun” studies identified a few precursors, such as the stomach acid reducer ranitidine. “But even though ranitidine has a high NDMA yield in the lab, it doesn’t occur in surface water,” he says.

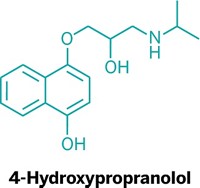

So Hanigan and his colleagues collected real water samples to search for possible NDMA precursors, he says. With surface water from 10 rivers in the U.S. and Canada and effluent from a sewage plant in Arizona, the scientists used liquid chromatography and quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry to hunt for compounds that shed dimethylamine groups that could potentially form NDMA upon chloramination. Applying a software program to the spectrometry data, they isolated an ion that confirmed the presence of methadone. Patients excrete methadone, prescribed to kill pain and kick heroin addiction, and it eventually slips through sewage plants to linger in rivers and lakes for several months.

When the researchers added monochloramine to a methadone standard, 60% of the methadone reacted to yield NDMA. The yield was impressive because only five other chemicals tested in previous studies had an NDMA yield above 50%, Hanigan says, “and none of them have been detected in wastewater effluent.” He calculated that methadone was responsible for up to 62% of the NDMA formed when he added chloramine to the sewage effluent sample.

The scientists then modeled a typical U.S. community of 100,000 people that consumes methadone at the average national rate and discharges treated wastewater diluted 40% by a receiving river. The team estimated that a downstream drinking water plant would produce drinking water with roughly 5-ng/L NDMA, a typical concentration measured in U.S. plants using chloramine.

“This paper shows that methadone can be a major source of NDMA in drinking water,” Richardson says. With EPA poised to potentially regulate NDMA in drinking water, the findings will help researchers determine how to prevent its formation, she says. Some utilities treat water with activated carbon or ozone before it enters the treatment plant to remove organic precursors of NMDA.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter