Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

ACS Meeting News: Porous Polymer Could Spot Traumatic Brain Injuries

by Michael Torrice

August 17, 2015

The forces from an explosive blast or a head-on tackle can shake a person’s head, causing damage that might trigger long-term neurodegeneration. To help doctors determine whether a patient might suffer from this type of traumatic brain injury, materials scientists have developed a thin polymeric film that changes color when struck with forces similar to those produced during football games or combat.

The material is light-weight and doesn’t require any power to function, so the developers think it could be affixed to helmets without burdening football players or military personnel as they work.

Younghyun Cho, a postdoc in the lab of Shu Yang at the University of Pennsylvania, presented the work Sunday in the Division of Colloid & Surface Chemistry at the American Chemical Society national meeting in Boston.

The sensor is basically litmus paper for forces, Yang told C&EN. Medical staff could check the film’s color and immediately know the magnitude of force delivered to the person’s head.

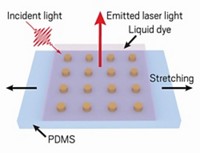

To design the sensor, Yang and her team relied on their experience with photonic crystals—materials with ordered nanostructures that interact with light to produce color. This so-called structural color can be found in plants, animals, and minerals; the iridescent colors of opals come from silica nanostructures, for example.

The researchers thought that such a crystal could serve as a force sensor, because a collision would compress these nanostructures, changing their shapes and, in turn, their color.

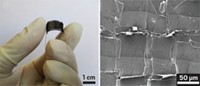

A few years ago Yang’s team reported such a crystal, but it required a complex, expensive production technique. In the new work, the researchers have used a simpler approach that starts with dipping a silicon wafer in a suspension of silica nanoparticles. The particles self-assemble into an ordered crystal on the wafer. The team then adds a thermoplastic, allowing the polymer to fill in around the particles and solidify. After dissolving away the silica with acid, the researchers are left with what they call an inverse opal structure—a material with an ordered array of voids where the particles once were.

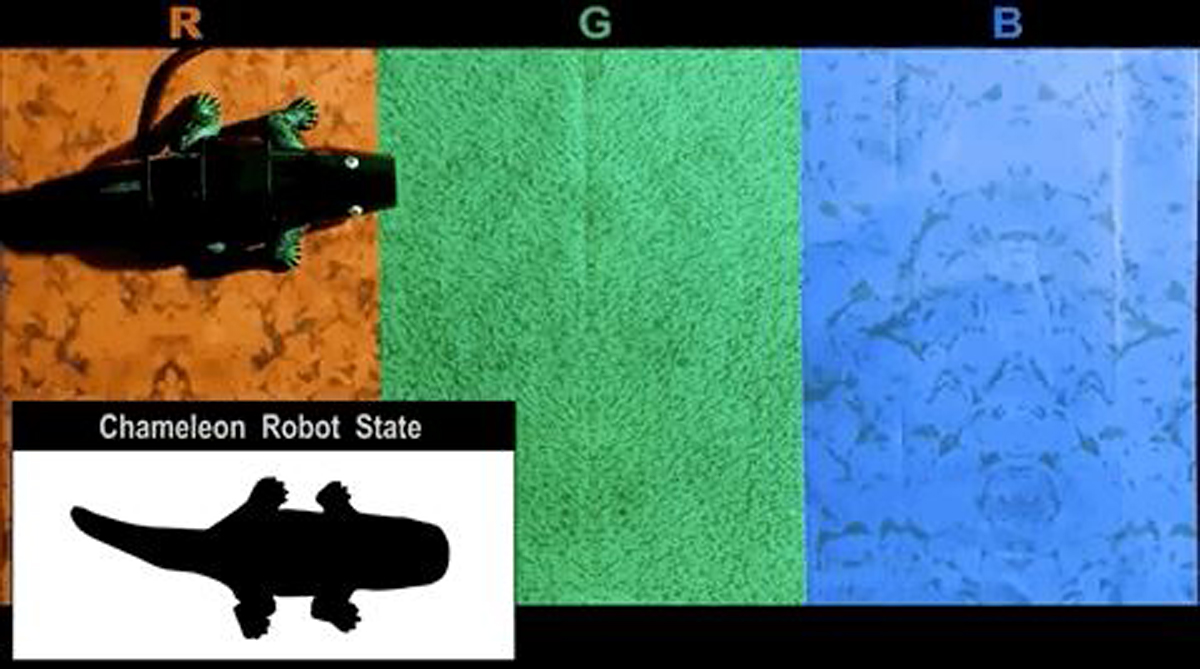

This material starts out orange-red. An applied force compresses these voids, shrinking their widths and shifting the color of the overall material first to green and then to purple and blue. Because of the plasticity of the polymer, the structural changes are not reversible, meaning the color change remains after the blast or collision. This would allow medics to read the sensor either in the field or at the hospital.

The researchers tested the films by pressing down on them with known force using a tiny fingerlike probe. The sensors could detect pressures between 10 and 20 MPa, which are comparable to impact forces experienced during a hard football tackle or car accident.

Yang says her team next wants to work with neuroscientists to start testing the sensor in more real-life situations.

The novelty of this sensor is its sensitivity, says Suzanne M. Balko of the Leibniz Institute for Polymer Research, in Dresden, Germany. The film’s color changes almost 6 nm in wavelength for every 1% change in its structure. Yang says this sensitivity is the highest reported in the literature to date.

But Balko points out that the sensors may not be able to respond to the high speeds of impacts seen on football fields. To allow them to work at those speeds, she says the researchers will need to tune the material’s properties, including its elasticity.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter