Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Analytical Chemistry

A New Fluorescent Protein For Studying Living Organisms

Pacifichem News: Engineered near-IR fluorescent protein could aid imaging of multiple biological processes in whole animals

by Stu Borman

December 18, 2015

Green fluorescent proteins (GFPs) revolutionized scientists’ ability to monitor happenings inside cells. But the glowing proteins have a serious limitation that prevents them from helping scientists watch biological phenomena in whole, living animals. The wavelengths of light used to excite GFPs are readily absorbed by animal tissue, making it difficult for researchers to peer past the surface of an organism. To overcome that limitation, some scientists have engineered fluorescent proteins that absorb and emit near-infrared (near-IR) light, which can penetrate through tissue.

On Tuesday at the 7th International Chemical Congress of Pacific Basin Societies, or Pacifichem, in Honolulu, scientists reported a newly engineered near-IR fluorescent protein that could improve whole-organism imaging of biological processes.

The new protein is the brightest in a bacterial class of phytochrome fluorescent proteins, and it emits close to the edge of the near-IR spectra. These features could enhance the sensitivity and ease of imaging experiments that monitor multiple biological processes at once.

Phytochrome fluorescent proteins bind near-IR absorbing tetrapyrroles called bilins. But the native proteins “are not meant to fluoresce,” explains biophysicist John T. M. Kennis of VU University Amsterdam, who was not involved in the new work. “They are signaling proteins that have evolved to detect near-IR light and give off a signal to the organism to act in certain ways. So these proteins have to be engineered to become fluorescent.”

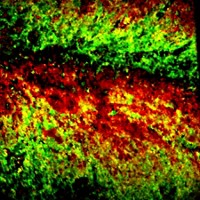

Vladislav Verkhusha and Daria Shcherbakova of Albert Einstein College of Medicine have been working on engineering the proteins to absorb and emit light from different stretches of the near-IR spectrum. Proteins with different spectral properties allow scientists to tag more than one type of cell, tissue, or organ so they can image them simultaneously.

Recently, Verkhusha, Shcherbakova, and coworkers found that they could tune the proteins’ spectral properties by changing the amino acid residue to which a bilin called biliverdin attaches to the protein. Their best success to date is a protein they call BphP1-FP (Chem. Biol. 2015, DOI: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.10.007). The emission of the new protein is blue-shifted by about 40 nm compared to native and previously engineered phytochrome proteins—from over 700 nm to 669 nm, near the edge of the near-IR region.

BphP1-FP also has a fluorescence quantum yield, a measure that contributes to the protein’s brightness, of 13%, “which is the highest ever reported for bacterial phytochromes,” Kennis says. He notes that the first reported near-IR bacterial phytochrome fluorescent protein, developed in 2009, had a quantum yield of about 7% and that there have been few improvements on that in the past six years.

Verkhusha and Shcherbakova’s team used BphP1-FP and a spectrally distinct phytochrome protein for multicolor imaging of different compartments in human cells. The group’s work suggests that “the ideal of the transparent mouse comes within reach,” Kennis says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter