Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Physical Chemistry

What will it be?

by Bibiana Campos Seijo

March 28, 2016

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 94, Issue 13

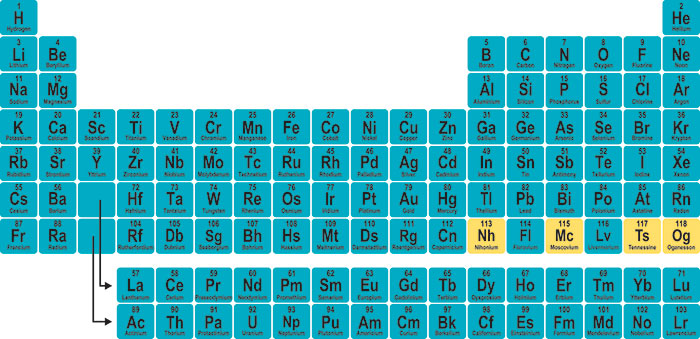

On Jan. 11, I dedicated part of my editorial to highlighting the official announcement that the seventh row of the periodic table had finally been completed as IUPAC (the International Union of Pure & Applied Chemistry) confirmed the validity of the experiments that produced elements 113, 115, 117, and 118.

It’s difficult to guess how the task of naming the elements is being handled, but what we know is that the clock is ticking. It takes between four and six months from the announcement for the institutions that made the discoveries to propose appropriate names. These are then subject to IUPAC’s approval because, contrary to popular belief, those institutions do not have an automatic right to choose a name. The proposed names and symbols are checked by IUPAC’s Inorganic Chemistry Division, presented for public review for a period of five months, and finally approved by the IUPAC Council.

While we wait for the process to run its course, Nature Chemistry just published a paper in which freelance writer Philip Ball, Worcester Polytechnic Institute professor of chemistry and biochemistry Shawn Burdette, chemistry writer and blogger Kat Day, UCLA lecturer and author Eric Scerri, and Stockholm University atmospheric chemistry researcher Brett Thornton attempt to predict the names for elements 113, 115, 117, and 118, currently known as ununtrium, ununpentium, ununseptium, and ununoctium, respectively.

Element 113 is the element of consensus, and the five experts forecast that it will be named after the country of its discovery—it was isolated at the RIKEN Nishina Center for Accelerator-Based Science in Japan. Ball argues it is nationalistic, but it’d mean a rebalancing of names outside the West (think polonium for Poland, francium for France, californium, berkelium, etc.).

There is also near consensus in relation to the naming of element 115, given that Russia’s Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (one of the organizations involved in the element’s discovery) has issued a press release in which it reveals that its proposal is going to be moscovium.

When considering element 118, the group is split between oganesson, in honor of Yuri Oganessian, who led the discovery teams at JINR as well as finding evidence for the island of stability that may exist after element 118; and moseleyon, after Henry Moseley, whose work showed that elements should be ordered by atomic number rather than atomic weight.

Element 117 is the most contentious, with the panelists splitting their votes among ghiorsonine, in honor of Albert Ghiorso who codiscovered 12 chemical elements; tennessine and quercine, after the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, with the first suggestion based on its location (Tennessee) and the second on the Latin word for “oak” (i.e. quercus); and schrodingerine, in honor of the father of modern quantum chemistry.

Plenty of suggestions here, but which ones get your vote? Let us know by writing to edit.cen@acs.org.

Views expressed on this page are those of the author and not necessarily those of ACS.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter