Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

For a new twist on a common lab tool, evaporation is friend, not foe

Relying on evaporation to mix droplets balancing on tiny pillars could offer advantages over microplates used for diagnostic and other assays

by Melissa Pandika

July 27, 2016

A new method that relies on evaporation of tiny droplets to mix reagents and drive reactions could offer advantages over traditional bioassay techniques (Anal. Chem. 2016, DOI: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b01657).

Clinicians and researchers frequently use microplates—flat plates comprising from dozens to thousands of small wells—for high-throughput screenings, bioassays, and diagnostics. In many cases, the reagents must be mixed, but current mixing methods pose limitations. For instance, magnetic stirrers in the wells can interfere with optical measurements, and vortexers can cause foaming. And for plates with wells as tiny as 1 mm across, the small sample volumes can evaporate unless incubated at high humidity or sealed with film or foil.

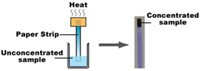

Researchers led by Jose L. Garcia-Cordero of the Center for Research and Advanced Studies at the National Polytechnic Institute in Monterrey, Mexico, designed an alternative that uses microsized pillars instead of wells. Droplets of the reaction mixture perch atop each pillar. The new assay exploits rather than prevents evaporation, relying on the process to concentrate and mix samples.

Garcia-Cordero came up with the idea while designing a cancer diagnostic platform. While letting evaporation concentrate proteins in a droplet, he and his colleagues observed that the proteins also mixed together in the droplet. They attributed this mixing to the Marangoni effect, where liquid flows to areas of higher surface tension. Evaporation can cause surface tension differences in the droplet that spur Marangoni currents.

Garcia-Cordero’s team wondered whether they could harness Marangoni currents for colorimetric assays. Earlier studies found that when droplets evaporate from flat surfaces, any particles they contain settle on the outer edges, leaving a dark “coffee ring” when dry. The researchers thought a drop sitting on a pillar would eliminate the coffee-ring effect because of its spherical shape, so they decided to test whether such a setup would offer both an easy way to mix samples plus a uniform, easy-to-read color.

To test their hypothesis, they conducted a glucose colorimetric assay on 800-µm-diameter, 1-mm-tall acrylic pillars fashioned with a mill machine. They pipetted an enzyme solution onto a pillar and let it evaporate in a low humidity environment to concentrate it before adding the glucose solution. The glucose undergoes a series of reactions catalyzed by the enzymes, forming a colored product. They performed the assay on a pillar at high and low humidity, and at low humidity on a flat surface.

They monitored the reactions for 20 minutes and took photographs. At high humidity, the droplet on the pillar didn’t evaporate or change color, suggesting that evaporation provides the mixing necessary for the reaction to occur. The droplet on the flat surface evaporated and changed color but demonstrated the coffee-ring effect. But as the droplet on the pillar at low humidity evaporated, its color changed. Garcia-Cordero’s team observed similar results with a colorimetric assay for protein.

The pillar platform doesn’t require mixing equipment and works with as little as 1.5 µL, comparable to the limit for microplates, saving time and reagent expenses, Garcia-Cordero says. And the plates are cheap and quick to make.

Ronald G. Larson, a chemical engineer at the University of Michigan, suggests that pipetting samples onto tiny pillars may be challenging. But overall, “it’s a neat idea. Even if this is not a sure-fire thing, it’s clever and interesting,” Larson says. “I don’t see any strong reasons why this wouldn’t have advantages.”

Garcia-Cordero says the group is now working to conduct a more definitive test of Marangoni currents and to optimize the platform for colorimetric assays on serum and other clinically relevant samples before expanding it to other types of assays.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter