Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Perfluorinated chemicals linked to military bases, airports

New analysis finds association between drinking water contamination and non-industrial sources

by Jessica Morrison

August 10, 2016

Drinking water contamination from perfluorinated chemicals is a known concern for communities near industrial sites in the U.S. where the chemicals were once produced. Contamination that extends beyond the reach of production facilities is coming from other sources, experts say.

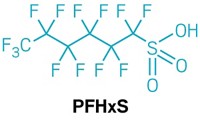

Researchers are now pointing to military bases, civilian airports, and wastewater treatment facilities as sources of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in ground and surface waters.

Xindi C. Hu of Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and colleagues report drinking water supplies of some 6 million U.S. residents exceed the lifetime health advisory levels for perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) set by the Environmental Protection Agency in May (Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2016, DOI: 10.1021/acs.estlett.6b00260).

Hu and her colleagues examined EPA’s national drinking water contaminant data for a suite of PFASs and analyzed 16 industrial sites, 664 military fire training sites, 533 civilian airports, and 8,572 wastewater treatment plants. They show a statistical association between the number of these facilities in an area and the concentration of PFASs in its drinking water.

“This study gives weight to what many of us had suspected for many years, which is that there is a very significant contribution of non-industrial sources of these chemicals to contaminated water supplies,” says Christopher P. Higgins, an environmental chemist and professor at Colorado School of Mines and co-author of the study.

The Department of Defense late last year began investigating contamination at military training sites where aqueous film-forming foams containing PFOS and related fluorochemicals that can degrade to PFOA or PFOS had been used for fire training exercises. In addition, the authors note that wastewater treatment plants are unlikely to remove PFASs through standard treatment methods.

“The authors are to be commended for taking EPA data and interpreting it for the public and decision makers,” says Jennifer A. Field, an environmental chemist at Oregon State University who was not involved in the work.

Military bases and airports are more abundant than manufacturing sites, Field adds. “This issue has the potential to touch every state.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter