Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Nobel Prize

Yoshinori Ohsumi wins 2016 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

Researcher's work provided the basis for understanding autophagy, or how cells degrade and recycle their molecular trash

by Sarah Everts

October 3, 2016

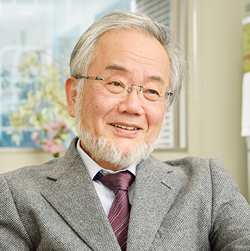

The 2016 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine has been awarded to Yoshinori Ohsumi, 71, a cell biologist at the Tokyo Institute of Technology “for his discoveries of mechanisms for autophagy.”

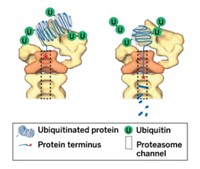

Autophagy is the process by which cells capture large dysfunctional proteins, aging organelles, and invading pathogens in vesicles and then send them to the lysosome for degradation, said Juleen Zierath, Chair of the Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine in announcing the prize. “Without autophagy our cells won’t survive.”

Dysfunction of the autophagy process is life-threatening from birth through old age. For example, autophagy is disrupted in Alzheimer’s disease, when toxic protein aggregates are not properly discarded. As a consequence drugmakers have continued to eye the pathway as a therapeutic target.

Although researchers had known since the 1960s that cells cleaned up their large cellular garbage by enclosing it in vesicle sacks and sending it to the lysosome for degradation, in the 1990s, when Ohsumi began his work, nobody knew how the system worked, and what machinery was involved, Zierath says.

At the time, “people were not that keen to study how cells got rid of their trash—it was not considered sexy,” says Anne Bertolotti, who studies autophagy at MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, in Cambridge, and who hosted a visit from Ohsumi just a few weeks ago.

2016 Nobel Prizes

C&EN’s coverage of this year's laureates.

Yoshinori Ohsumi, Physiology or Medicine

Yoshinori Ohsumi, Physiology or Medicine

David Thouless, Duncan Haldane, and Michael Kosterlitz, Physics

David Thouless, Duncan Haldane, and Michael Kosterlitz, Physics

![]() Jean-Pierre Sauvage, J. Fraser Stoddart, and Ben L. Feringa, Chemistry

Jean-Pierre Sauvage, J. Fraser Stoddart, and Ben L. Feringa, Chemistry

And don't forget to check out all of C&EN’s coverage of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, including our analysis of what chemistry wins and who’s been nominated.

Ohsumi first noticed that you could induce baker’s yeast cells to produce autophagy vesicles under low nutrient conditions. This observation gave scientists the first method for controlling and studying the process, Bertolotti says. Then, “in a heroic effort, Ohsumi studied mutant yeast under the light microscope, one cell at a time, to figure out which genes were involved,” she adds.

Over the years Ohsumi continued to tease apart the mechanisms of autophagy and to show that similar machinery existed in more complicated organisms, including humans. Notably, he showed that the lysosome wasn’t just a waste dump, it was a recycling plant, Zierath adds. In some cases, discarded components are actually broken down in the lysosome and reused to make new proteins.

“Ohsumi is the father of this field,” Bertolotti says. “It is a really well-deserved prize.”

Ohsumi was in the lab when he received the famous phone call. "I was surprised," he told Adam Smith, chief scientific officer at Nobel Media. Since his original discoveries, autophagy has become a large research field, Ohsumi added. But “even now we have more questions than when I started.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter