Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Analytical Chemistry

Toward a blood test for prion disease

Technique diagnoses small group of patients with 100% sensitivity and accuracy

by Stu Borman

December 28, 2016

In the mid-1990s, researchers discovered that a version of mad cow disease called variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) was disabling and killing people. Infectious proteins called prions could spread vCJD from one person to another, through pathways such as contaminated blood transfusions. The infectious prions—misfolded versions of normal prion proteins—caused a scare, particularly in the U.K., where most vCJD cases occurred.

Since that time, researchers have been trying to develop tests that can detect infectious prions in blood so infected people can be reliably diagnosed. Neurological symptoms, progressive dementia, and magnetic resonance and electroencephalogram results can indicate the possibility of vCJD, but currently a diagnosis can only be confirmed by postmortem examination of brain tissue. No vCJD blood tests have been approved because they have so far lacked adequate sensitivity and have sometimes given inaccurate results, such as false positives.

Researchers have now developed and demonstrated the first tests sensitive enough to detect vCJD infection accurately and with 100% sensitivity in patient blood or plasma. Claudio Soto of the University of Texas Houston Medical School, Daisy Bougard and Joliette Coste of the University of Montpellier, and coworkers carried out the studies (Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf6188 and 10.1126/scitranslmed.aag1257).

The prevalence of vCJD has declined to only about two diagnosed cases per year worldwide, compared with an average of about 15 per year from 1996 to 2011. Nevertheless, immunohistochemical surveys of U.K. tissue samples have indicated that 1 in 2,000 people in the U.K. may be asymptomatic vCJD carriers and could spread the disease further if not identified.

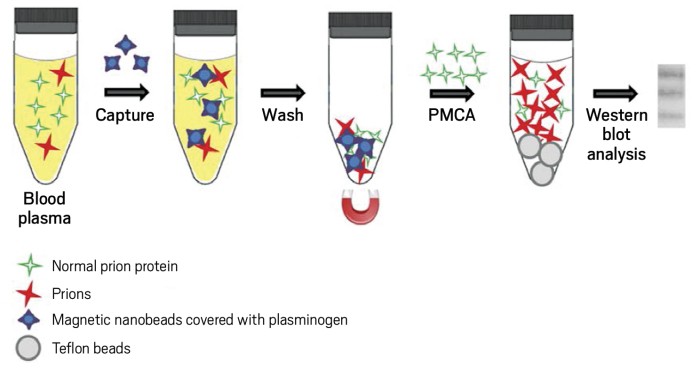

To carry out the new blood tests, Soto, Bougard, Coste, and coworkers use a surfactant or magnetic beads to concentrate prions in blood or plasma, respectively. They then use protein misfolding cyclic amplification (PMCA), a technique Soto and coworkers helped develop earlier, to amplify the small numbers of prions in blood or plasma from infected patients. PMCA uses the infectious prions as seeds to convert normal prion protein into more of the infectious form. The scientists then use Western blotting to detect the amplified infectious prions.

Up to now, most vCJD blood tests have been sensitive enough to diagnose only about 70% of cases in blinded studies. The new blinded studies correctly identified 100% of infected cases in blood from 14 patients (Texas study) and plasma from 18 patients (Montpellier study), without finding any false positives in a few hundred uninfected controls. The Montpellier tests also identified early cases of previously undiagnosed vCJD in two patients who developed the full-blown condition one to three years after tests were conducted. Technical refinements in PMCA technology and the use of the initial prion-concentrating steps, which had not been used earlier, could be responsible for the improved performance of the new procedures, the researchers say.

“These studies are certainly an important contribution to the development of a vCJD blood-based test,” comments prion disease specialist Christina D. Orrù of the U.S. National Institute of Allergy & Infectious Diseases. Such a test “would reduce the risk of disease transmission and possibly, in the future, allow for better therapeutic treatments of prion disease patients. The next step might be to optimize these techniques for widespread, high-throughput implementation.”

“The two papers reflect the immense progress testing has undergone during the past decade,” adds prion disease expert Paul Brown, now retired from the National Institutes of Health. The tests “would have been crucially important had they been developed while the vCJD epidemic was in full swing, but they may continue to be important for detecting asymptomatic carriers of the infection and in the event of a future outbreak,” he says.

In addition to use of PMCA to diagnose vCJD, “we hope our technology could help with the development of an early diagnostic assay in other protein-misfolding diseases” such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, which are far more prevalent, Bougard says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter